Robert Hollands

When I mentioned to a number of friends that I was going to Geneva, Switzerland to conduct research into alternative cultural spaces, most shook their heads in disbelief. ‘All I think of when I hear the word Geneva’, one of them exclaimed, ‘is rich people, watch-making, non-tax paying corporations, and the Red Cross’. I think this is probably a fairly popular stereotypical view of the city. However, underneath exterior, lies an impressive counter-cultural legacy. Geneva is currently in the midst of a battle to retain its autonomous cultural heritage, and in doing so, is simultaneously challenging the dominant neo-liberal urban development model.

From nightlife to declining alternative cultural spaces

I initially encountered the city of Geneva in 2011 when I was asked to give a keynote presentation on my research into nightlife in the UK at a high profile event, sponsored by the department of culture, entitled ‘Etats Généraux de la Nuit’ (which translates as ‘General State of the Night’). Nightlife had become a significant political issue in 2010 with the production of an important research report ‘Journey to the End of the Night’ which suggested, amongst other things, a lack of diverse and affordable nightlife venues in the city. Street protests erupted when the closure of two mainstream nightclubs, over supposed health and safety issues, led to one of Geneva’s alternative cultural venues, L’Usine, to go on strike in response to the overcrowding of its premises. Over the course of two weekends, these ‘night strikes’, involving around 5000 young people, took the form of carnivalesque late night street parties, complete with sound systems, dancing and protest banners, with the aim of demanding more varied and affordable nightlife venues. I have subsequently, together with a number of activist-colleagues from Geneva, written a book chapter, to theorise and make sense of these events through ideas associated with urban cultural movements.

I have also learned a lot about Geneva’s impressive counter-cultural history and the ongoing struggles of artists, musicians, and alternative cultural organisations to survive in the city, which links with my current research project (funded by the Leverhulme Trust) entitled ‘Urban Cultural Movements and the Struggle for Alternative Creative Space’ with the aim of exploring how alternative cultural production can begin to challenge how we live, work and play in the neo-liberal city. While the term ‘alternative’ remains a difficult concept to define, but I use it here to signal cultural forms that attempt to remain autonomous and self-managed, and which oppose or challenge the market-based domination of culture (below I use the term interchangeably with ‘autonomous’ and ‘independent’ cultural producers).

Geneva forms an excellent case study for such research. For instance, in 1995, it was a heavily squatted city, with an estimated 120 buildings occupied by some 2800 inhabitants. In the last twenty years however, it’s vibrant artistic counterculture has been challenged by corporate and entrepreneurial urban development, including soaring property prices/rents, increased gentrification of cultural life, and draconian legislation preventing the illegal occupation of buildings. Iconic buildings like Artamis (literally meaning ‘friends of art’), an emblematic occupied industrial space that was home to over 200 artist/ artisans, and Rhino, primarily a housing squat opened in 1989 (although it also provided space for independent cinema, music, and a bar and restaurant), were forced to close, despite significant protests, in 2008 and 2007 respectively.

Some resisters began to talk of the ‘cultural sterilisation’ of alternative Geneva, and in many cities such property-led urban speculation and a housing shortage, may have signalled the end of the autonomous cultural sector altogether which relies heavily on the availability of unused buildings. However, a number of factors have mitigated against this happening in the city. First, it appears that numerous state and city councillors either were former squatters or were people who understood the contribution such spaces made to the city, both in terms of cultural activities but also with regard to their affordability, diversity, and accessibility. Second, the Genevan state appears wealthy enough not to be forced to sell off all its public assets to ‘balance the books’ This has meant that, in some cases, public buildings and land have not necessarily been auctioned off to the highest private bidder or developer, as has happened in other European cities, but rather they can be considered as spaces for local independent cultural producers. Third, many artists and cultural actors have maintained squatting traditions like self-management (autogestion as its referred to in Switzerland) and collective decision-making within their organisation, and have generally been in solidarity with one another when conflictual issues have arisen (see below for example). Finally, through a combination of its own resistant ethos (for example, most venues and festivals seem relatively immune to private sponsorship) and due to the city of Geneva’s lack of interest, or need, to target bohemian types of tourism (like for example Berlin does), the alternative cultural sector has been relative immune to incorporation into urban branding strategies.

Alternative Geneva fights back

Returning to the city four years later, it was evident that there were new seeds of dissent and organisation happening amongst the autonomous cultural sector. For example, I was pleasantly surprised to see that a handy map of alternative cultural spaces in Geneva had been produced on the occasion of the first Biennial of Independent Art Spaces (BIG), entitled ‘Carte Des Lieux Culturels Independants A Geneve’ complete with a short write up of forty-four venues across the city. How many cities its size (population 200,000) can boast this array of alternative places? I was also lucky enough to be able to visit a number of those spaces and talk to various people in this movement, and what I found, was indeed, quite inspiring.

Map of alternative cultural venues, Geneva (photo by author)

I spent a day in Theatre du Galpon (which was formally housed in the squat Artamis), a wonderful (but apparently temporary) theatre space constructed in a wooded area of natural beauty. They were hosting a debate about the future of alternative cultural space in the city. Some two-hundred and fifty people showed up to participate in a four hour debate, including an inspiring presentation by the Berlin based collective Stadt von Unten (translated as City From Below), a group of radical architects, artists, tenant and community groups, who successfully blocked a gentrified urban development in Kreuzberg. The panel included an array of speakers: state politicians in urban development and culture planning, artists, academics, and ex-squatters. While it was reported in the press that the politicians in attendance were generally supportive of the cause there was, in fact, quite a ‘lively’ debate around who should be responsible for making the case for more alternative space, and whether there really was the political will to support such demands.

Panel debating the role of cultural actors in the production of urban space, Theatre du Galpon, Geneva, 9.11.15 (photo reproduced courtesy of Elisa Murcia Artengo)

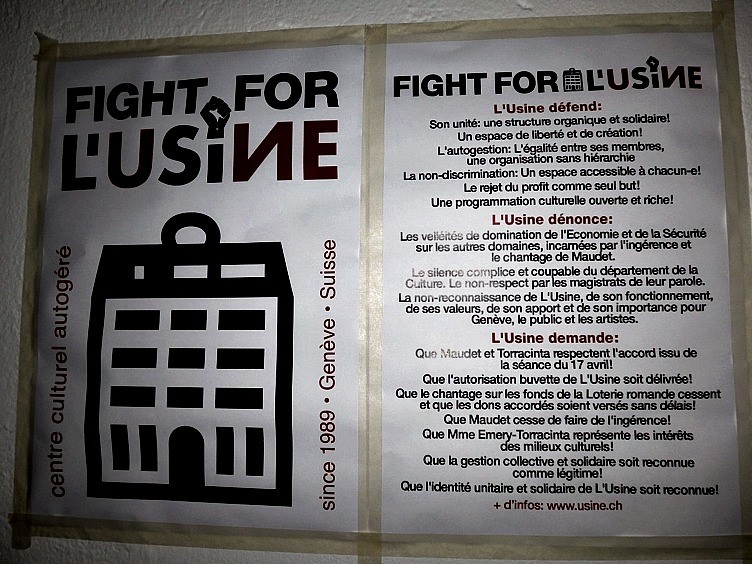

The evening also included its own ‘mini-protest’ over who was responsible for, and how to resolve, a new political conflict over alcohol and food licensing affecting the alternative sector. Not surprisingly, L’Usine was again at the sharp end of this protest. In response to State demands that they comply with licensing laws by having an alcohol license for each of the different venues within the cultural centre (including the theatre, cinema, nightclub and bar), L’Usine has stood firm by striking once again, this time concerning the ‘over-regulation’ of alternative sector. They argue, that as a collective of collectives, they should only be required to have one alcohol license and that it is the collective, not named individuals, that should be held responsible for when the terms of the licence are breeched. While in private, I heard a number of differing views about the situation from other independent cultural producers, in public all were in solidarity with L’Usine’s stance as it represented a potential threat to the entire alternative sector. In an interview with one of their employees, it was clear that the dispute was taking its toll on people working in alternative cultural venues, when they admitted they might have to leave the sector in the future because ‘we spend more time fighting with the state to comply with bureaucratic regulations, then we do creating an alternative cultural experience’.

Poster outlining the arguments for L’Usine’s latest cultural struggle (photo by author)

In addition to Theatre du Galpon and L’Usine, I also was able to visit two other venues: the intriguingly titled Embassy of Foreign Artists, a lovely state-funded space for artists outside of the country to experience a residency in Geneva, and Le Velodrome, a public housing block with artistic and industrial spaces in the basement of the building. Both represent some of the other challenges facing the alternative cultural sector – namely the temporary nature of the spaces and the contradiction of being either state-funded or state dependent. For instance, the future of the Embassy was clearly dependent on future funding and whether the state might require the building for some other purpose. Additionally, an artist at Le Velodrome said to me that they might just be viewed simply as ‘state tenants rather than alternative cultural producers’, despite the fact that this cultural space was run largely on a self-managed basis. Both places reveal the problem of how to create an enduring and lasting autonomous cultural infrastructure when this sector is unable to have permanent control or ownership of their own premises.

Artistic ‘dark matter’ and urban creative struggles

These kinds of debates and issues are currently being mooted academically in fields like Geography, Sociology, and Cultural Studies, particularly in discussions around the political role cultural producers might play in the re-making of urban space. For instance, the well known Marxist Geographer David Harvey, in his book Rebel Cities, has argued that the contradictions of the current neo-liberal city for the artistic community means that the struggle to distinguish places through specific reference to ‘symbolic forms of culture’ can opens up new spaces for alternative activities and political struggle, and suggests ‘…there are plenty of dissident sub-currents and discontents to be detected among cultural producers’ (p. 89).

Despite the problems and dilemmas faced by alternative cultural producers in Geneva, I was heartened by the sheer talent and tenacity of this ‘post-squat’ movement. Despite the odds, their activities and fighting spirit gives one pause for hope for the beginnings of a different kind of city to the corporate neo-liberal model which appears to be dominant everywhere. Let us hope that ten years from now, that my friend, and many others, will know Geneva as a vibrant city of alternative urban culture, rather than just a repository for global capital and one of the most expensive cities in the world.

Robert Hollands is a Professor of Sociology at Newcastle University and his most recent research project is on urban cultural movements and the struggle for alternative creative space in cities

Image Credit: Protesting the closure of the Rhino Squat, Geneva, 2007 (photo provided courtesy of Laurent Girod)