Steven Roberts, Karla Elliott, and Marcus Maloney

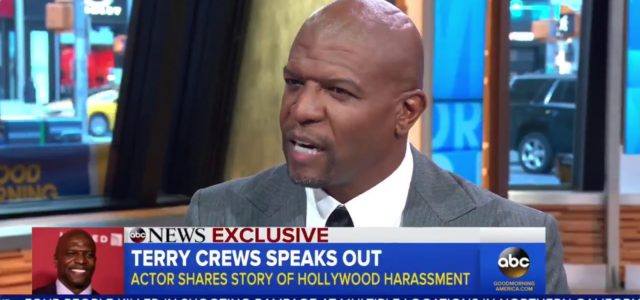

Building on earlier work by activist Tarana Burke, in October 2017 a group of women actors – including Ashley Judd, Alyssa Milano, and Rose McGowan – drew attention to an ingrained culture of sexual harassment in Hollywood, giving the hashtag #MeToo global prominence. The voices of these and other women survivors were accompanied by those of a handful of men who had been victims of assaults by other powerful Hollywood men. Perhaps the most prominent of these male victims of violence was actor Terry Crews. In his testimony to the US senate in June 2018, Crews echoed his women counterparts in his condemnation of the toxicity of masculinity, which has allowed harassment, sexual harassment, assault and violence to thrive. Crews has since been critical of the complicity around these issues driven by the silence of other men.

For seemingly ‘turning on his own’, Crews faced an ugly, aggressive and not insignificant backlash from men. Paul Elam, a leader of the men’s rights movement in the US and beyond, called Crews ‘pathetic’ and a ‘shameless cuck’ for suggesting that masculinity is a negative force. Actor and rapper 50 Cent mocked Crews’ testimony with a series of now deleted ‘joke’ images posted on Instagram. 50 Cent primarily cast doubt on Crews’ assault claim because Crews didn’t react violently (read, ‘appropriately manly’) when assaulted.

Under the banner of #NotAllMen, many others have, again predictably, sought to distance themselves from the sexual assaults, rejecting that masculinity and social norms have played a role and suggesting instead such intolerable behaviour is the action of a few bad eggs. The #NotAllMen approach, as many women have documented, serves to ‘derail and dismiss the lived experiences of women and girls’. An impressive takedown of the approach is offered by Aaminah Khan and Melissa A. Fabello at Everyday Feminism.

In addition to these important critiques, we propose that considerable value in the effort for gender equality lies in also highlighting the ways that masculinity is actually a highly contested arena. This is not about shutting down or underplaying women’s experiences. Far from it. Instead, this is about offering a specific message to men, one that involves highlighting that those loud voices of toxic masculinity actually represent just one discourse among many, and that other, healthier narratives of masculinity exist. We don’t want to imply that a majority of men don’t need to change. Men’s complicity with norms of toxic masculinity in part underpins gender inequality, gendered and family violence, and harassment, sexual harassment and assault. This complicity needs to be challenged, and men in general need to step up to the challenge of transforming themselves, their friends and these toxic norms. But, alongside the highly vocal, toxic voices of those such as Elam, 50 Cent, and proponents of the #NotAllMen approach, there are other, healthier narratives of masculinity and of ‘how to be a man’ circulating and available. This message to men provides the foundations for moving towards a reworked set of culturally ascendant norms for men and masculinity that are healthier for everyone.

Bear with us as we dip into a bit of sociological theory to explain this further.

Thanks to the work of Raewyn Connell (e.g. 1987), masculinities theory has long established that a minority of men practice a version of masculinity that is both normative and hegemonic – this is the version of masculinity that sets the rules of how to be a man in any given culture. Hegemonic masculinity is often associated with strength, anti-feminine sentiment, and the capacity to wield power. The rhetoric outlined above by Elam, 50 Cent, and others like them corresponds with this notion, given it ‘supports the gender hierarchy and subordinates marginal masculinities and men who do not comply with it’.

In popular discourse, the term toxic masculinity is normally used to describe a version of masculinity similar to hegemonic masculinity. Connell also theorises complicit masculinity, where certain privileged men can benefit from hegemonic masculinity without having to live up to its standards themselves. In Terry Crews, we have someone who is engaging in a version of protest masculinity. Some have insisted that protest masculinity is about the use of violence and aggression by subordinated men, but it is better understood as being ‘a gendered identity oriented toward a protest of the relations of production and the ideal type of hegemonic masculinity’. Such protestation is perhaps more widespread than is first imagined.

An example of this is found in research that two of us recently conducted into one of the computer gaming community’s largest social media platforms, the Reddit subreddit ‘r/gaming’ (Maloney, Graham, Roberts 2017). Reddit itself is widely perceived to be a highly masculinised arena in which toxic masculinity thrives. The Reddit gaming community could be argued to represent an even more hyper masculinised space, with the online gaming community having been positioned by many academics and journalists as being rife with sexual harassment and more generally as ‘an unpleasant or openly hostile space for females’ (Ratan et al. 2015: 440). This was famously exemplified in the 2014 Gamergate scandal, where prominent women members of the community suffered sexualised and often violent online harassment from anonymous male gamers. Further the website Fat, Ugly or Slutty, for example, details women’s gamers broader experience of being demeaned online by their male counterparts.

Our research examined a representative sample of the six million user comments entered into r/gaming during 2016. We extracted three random samples of 1500 comments that included any feminine gendered language to help create a digestible model. We then filtered for language we determined reflected attitudes towards women and girls, and we subjected these comments to close qualitative analysis. The stereotype of the sexist attitudes associated with ‘geek masculinity’ proved to be more complex; instead of being chiefly governed by a toxic, hegemonic masculinity, r/gaming is best viewed as a highly contested community divided along progressive-reactionary lines. So, alongside toxic and hyper-masculinised discourses within this Reddit gaming community, we also uncovered a comparably sized set of very different voices, ones clearly positioned against the toxicity with which the community has become associated.

This is just one arena of contestation in what appears to be a changing, but far from fully changed, set of rules for being a man in the ‘Global North’. For example, we have each pointed in our research to aspects of masculinity that appear to be in flux and offer possibilities for some progressive movement. This includes the emergence of caring masculinities, where men are encouraged to adopt values of care and interdependence and reject domination and violence; an improved set of attitudes among working class British young men towards so called women’s work in the settings of paid work and household labour (Roberts 2018); and a complex but improved articulation of homosocial intimacy among ‘ordinary’ young men, but also among significant cultural influencers such as YouTube celebrities. We do not underestimate the degree of change that is still required, nor the level of entrenched misogyny that underpins women’s daily experiences of harassment and gendered violence in many forms. Indeed, in our accounts of changes in masculinities, we have also documented the persistence of problematic behaviours alongside some positive changes.

Working our way back to Crews, what was striking to us in the reaction to his testimony was first and foremost the defensive reflex employed by those who espouse hegemonic masculinity. Secondly, though, was that Crews’ emboldened act of protest masculinity was in some ways undermined when journalists reporting on the story failed to mention Crews’ many supporters (of all genders) – one look at his Twitter feed illustrates many supportive comments from fellow actors and members of the public. Indeed, at the time of writing, the most prominent comment – as determined by community support – containing reference to the name Terry Crews is from a man who explicitly supports Crews’ position: ‘Good for Terry taking a stand against assholes in Hollywood. More people need to take a stand like him’ [Shade Aurion, June 27th]. Our point here is that there are other, healthier, more equal voices about men and masculinities out there, and these are the male voices that need to be fostered and promoted to men.

These more positive stories about men and masculinity need to be told. The ‘fight’ for masculinity is a hotly contested terrain, as per our own research into a wider variety of ‘masculine spaces’ and behaviours. By exposing these kinds of contestations, we argue, we stand a better chance of convincing men to reject negative, harmful and damaging positions. Wider changes in masculinities and protestations against hegemonic masculinity, when highlighted, offer the possibility of undermining the prescriptive capacity of the hegemonic norm. This then offers men, especially young men, examples of other, healthier, more equal, more caring ways of being a man.

Acknowledging the alternative voices we’ve touched on here can help critical scholars and gender change advocates challenge the loud voices of toxic masculinity that feature so prominently in popular discourses. The damage caused by those negative voices should of course never be minimised, but it will be helpful to minoritise them (Roberts 2018). This will potentially help to reframe the story about the possibilities of and for masculinity, and in turn contribute to the pursuit of gender equality.

References:

Connell, R. W. 1987, Gender and power: society, the person and sexual politics, Polity Press, Cambridge.

Maloney, M., Graham, T. & Roberts, S. (2017) The Last Dude Guy on Earth: Masculinity in the Reddit gaming community. TASA Annual Conference, Perth, November 30th 2017.

Roberts, S. 2018. Young working-class men in transition. Routledge.

Steven Roberts is Associate Professor of Sociology at Monash University. His recent publications relevant to the above article include the monograph Young working-class men in transition (Routledge, 2018), and the edited volumes Debating Modern Masculinities (Palgrave, 2014) and Masculinity, Labour and Neo-Liberalism (Palgrave, 2017, co-edited with Charlie Walker). Karla Elliott is a Research Fellow in the Gender and Family Violence Focus Program, Sociology, at Monash University in Australia. Her research focuses on masculinities, gender, and intersections of masculinity with family violence. Her most recent article explores possibilities for caring masculinities for fostering gender equality. Marcus Maloney is Lecturer in Sociology at Coventry University. His research centres on media and popular culture especially its digital manifestations. He is author of the book The Search for Meaning in Film and Television: Disenchantment at the Turn of the Millennium, (Palgrave, 2015) and recent articles on violence in video games, and performances of masculinity in YouTube video game vlogging.