Mark Monaghan and Jo Ingold

The Integrated Communities Strategy Green Paper is an ambitious document with the fundamental aim of providing the means to achieve the building of stronger, more united communities across England. Throughout the document there is a premium placed on how the measures proposed in the Strategy can be evaluated and what lessons can be learned to assess its potential success. This is to be cautiously welcomed bearing in mind Keynes’ somewhat timeless adage that there is nothing that governments hate more than being well informed, as it makes the process of decision-making that much harder.[1]

Of note in the strategy is a desire to incorporate evidence into the policy process, with frequent mentions of a commitment to discovering ‘what works’. In this short article, we consider the way that evidence has been framed in the Green Paper, drawing on lessons from a perspective we call ‘Evidence Translation’ and the central role of ‘evidence translators’ within this.

Evidence-based policy?

Over recent decades, much attention has been directed towards the role of evidence in policy making. Although this has a long lineage, it was given renewed emphasis in the late 1990s by New Labour and their desire to develop policies devoid of ideology and based on the best available evidence.[2] Since then an entire infrastructure within government has been continuously buttressed. For instance, HM Treasury’s Magenta Book[3] provides guidance to policy makers and analysts (economists, social researchers, statisticians and operational researchers) at all levels of government (and central and local) for the design and management of evaluations of government projects, policies and programmes. The Magenta Book is a companion to HM Treasury’s Green Book.[4] This constitutes ‘binding guidance’ for departments and government agencies undertaking economic appraisals when developing policies and programmes. This incorporates the ‘ROAMEF’ cycle (Rationale, Objectives, Appraisal, Monitoring, Evaluation, Feedback), intended to represent the UK policymaking process.

Despite these attempts to provide guidance for policy makers and analysts regarding the harnessing and utilisation of evidence, there is a lack of data about evidence use within government. The above publications have possibly added to, rather than alleviated, this void: the guidance is, at best, incomplete and abstract rather than reflective of the realities of policymaking. For instance, at no stage does the Magenta Book consider how policymakers can assimilate knowledge into policy. Additionally, EBPM has latterly become a point of derision to some extent. For example, Michael Gove’s criticism of experts and before that Dame Louise Casey’s notorious comment about No. 10 and EBPM being a precursor to policy inaction.

Green Papers and Policy Development: The Role of ‘Evidence Translation’

In the UK (and elsewhere) Green Papers serve as discussion papers for ‘proposals which are still at the formative stage’. Not all discussion papers are put on general release and many are sent to a pre-selected list of consultees, a decision usually at the discretion of the administering Department. A critical (but usually implicit) defining feature of Green Papers concerns their framing of an issue, which, in turn, influences the kinds of evidence that are deemed permissible and those that are not.

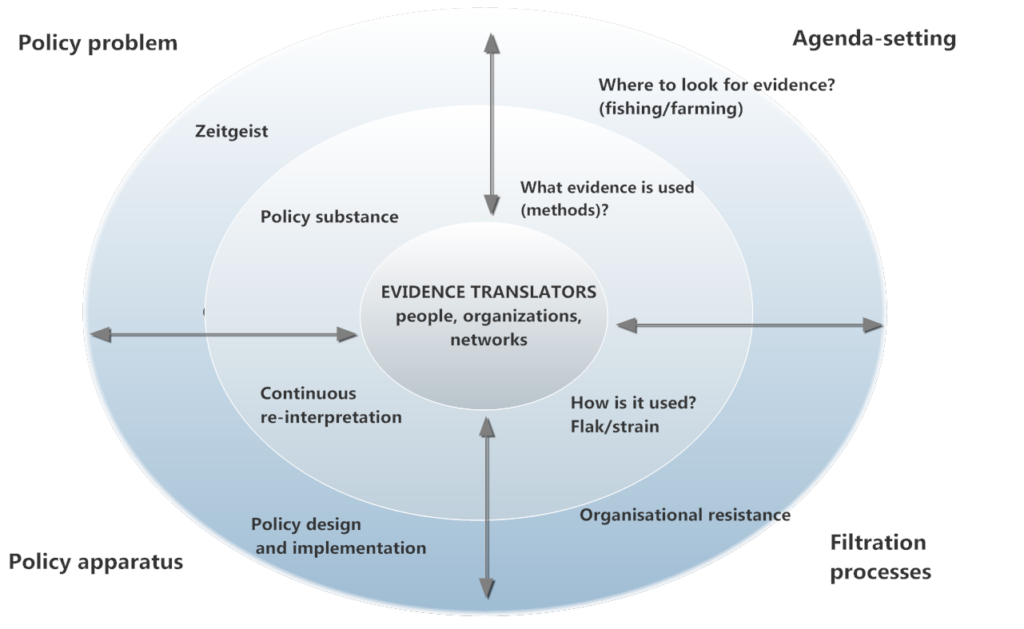

In an attempt to shed light on the process of how evidence is used in policy making (the ‘evidence-policy connection’), we have suggested a model of ‘Evidence Translation’, based on research with a large UK central government department (see Figure 1).

The model suggests that five, inter-related factors broadly shape the process of translating evidence into policy.[5] Below we set out how these relate to the Integrated Communities Strategy Green Paper:

- The substantive nature of the policy issue or problem determines the kind and extent of evidence used.

The challenge is presented as being primarily an issue about ‘a worrying number of communities, divided along race, faith or socio-economic lines’ (pp.11-1). This, in turn, leads to several factors that need to be addressed: a) the level and pace of integration; b) school segregation; c) residential segregation; d) labour market disadvantage; e) lack of English language proficiency; f) personal, religious and cultural norms, values and attitudes; g) lack of meaningful social mixing.

But how are these identified and on what grounds? Perhaps ironically, it is Dame Louise Casey’s Review that is brought to the fore as dominant evidence upon which the Green Paper is based. Dame Casey has been a powerful policy entrepreneur and powerful broker of policy ideas since her early days as the ‘homelessness czar’ and is known for her often outspoken views on policy (as well as perhaps a relative disdain for careful evidence reviews).

- Agenda setting and policy framing influence the search for permissible evidence.

In the Integrated Communities Strategy, evidence is synonymous with evaluation, it is ex post facto. This conflation also downplays the effort has been expended by researchers trying to shape the policy field ex ante through, for example, systematic reviews. Systematic reviews are prognostic as opposed to more diagnostic evaluation research. Systematic reviews aim to net and assemble nascent research in any given domain. In effect, they involve researchers undertaking a scientific stock taking exercise on any given topic and so, in theory, arguably stand the best chance of providing the evidence-base about ‘what works’ for policy decisions. It comes as something of a surprise and missed opportunity that in the Green Paper there is almost an absence of evidence from systematic review.

- Specific filtration processes are at play in the relationship between evidence and policy.

The kinds of evidence that are deemed useful to policy makers and have powerful advocates tend to survive, whereas critical evidence falls by the wayside. Sometimes this is an issue of method. Ray Pawson highlights how because EBPM emerged from evidence-based medicine there has been a ‘fairly seamless’ adoption of a ‘gold standard’ of the randomized controlled trial (RCT) (preferably with hidden allocation) from health into other policy areas. Large-scale quantitative research is also favoured.[6]

In the Green Paper (and the Casey Review) the kinds of ‘evidence’ that predominate are from powerful policy entrepreneurs e.g. the Casey Review and largely quantitative evidence from large-scale social science research in the upper echelons of the evidence hierarchy (Home Office Statistical Bulletin on Hate Crime Research; Race Disparity Audit of Public Services; British Social Attitudes Survey (BSAS) on Racial Prejudice; iCOCO Foundation Report on School Segregation). These suggest the privileged position of certain types of evidence that, in effect, border on reportage and audit. In our research BSAS was a powerful barometer of public opinion and, therefore, valued by Ministers and utilised by government analysts, but smaller (often qualitative) studies were less likely to survive the filtration process (in relation to the Green Paper this includes British Academy’s Collection of Essays and Case Studies Showcasing Innovative Local Integration Projects).

- The apparatus for policy design and implementation can have a direct bearing on the kinds of evidence used and omitted.

The policy apparatus includes the legislative process, but in this dimension we also point to the importance of the interpretation and re-interpretation of the framing of the policy problem as well as the evidence base during the policy cycle. Effectively Green Papers set the direction of policy travel, flagging up key questions about aspects of policy that are not yet fully decided. However, there is often very little substantive change to be seen between draft proposals in a Green Paper and the resulting White Paper before it enters the legislative process. Consequently, Green Papers can operate with a somewhat one-dimensional understanding of evidence, something which could be seen as their ‘hidden’ function.

- At the centre of the Evidence Translation model and crucial to every stage of it are ‘Evidence translators’ – government analysts or policy officials who play a decisive role in relation to each stage of the translation process.

The role of evidence translators with regard to Green Papers is critical and largely under-stated. Firstly, during the early stages of the policy process it is ‘evidence translators’ in the form of analysts that tend to undertake the ‘rapid evidence reviews’ that form the basis for many Green Papers. These reviews require civil servants to fairly quickly establish where the weight of evidence lies on particular issues. In many cases this involves reverting to ‘tried and tested’ kinds of evidence, which are often influenced by somewhat hidden evidence hierarchies.

After the Green Paper…

Evidence translators are also critical at the stage of translating a range of views about issues raised in a Green Paper into the resulting White Paper. Clarity on who undertakes such tasks and what their framing of the issues, including how views and opinions on issues are weighted, is of central importance. Yet questions remain. Undoubtedly the views of some contributors are prioritised over others. How are critical views dealt with? Which kinds of evidence dominate and eventually determine the direction of policy? Submissions to consultations are largely via organisations and by individual academics and researchers. However, a key question is whose views are excluded in this process (such as individuals who are not necessarily adequately represented by a specific interest group)? At a time when ‘people-powered’ organisations (e.g. 38 Degrees and others) can facilitate individual citizens to quickly submit views to government consultations, is this kind of opinion downgraded because submissions are often similar, or is a ‘weight’ of opinion gauged as representing strong views on an issue? Only time will tell, but if the Green Paper provides the blueprint for the White Paper then it is likely to be a case of survival of the evidence that fits.

Notes

[1] Skidelsky, R. (1992). John Maynard Keynes: the economist as saviour, 1920-1937 (Vol. 2). London: Macmillan.

[2] Blunkett, D. (2000). Influence or irrelevance: can social science improve government. Research Intelligence, 71(6), 12-21.

[3] HM Treasury (2011) The Magenta Book: guidance notes for policy evaluation and analysis. London: HM Treasury (Magenta Book Background Papers).

[4] HM Treasury (2011) The Magenta Book: guidance notes for policy evaluation and analysis. London: HM Treasury (Magenta Book Background Papers).

[5] Ingold, J., & Monaghan, M. (2016). Evidence translation: an exploration of policy makers’ use of evidence. Policy & Politics, 44(2), 171-190.

[6] Pawson, R. (2006). Evidence-based policy: a realist perspective. London: Sage.

Mark Monaghan is Lecturer in Criminology and Social Policy at the University of Loughborough. Jo Ingold is Lecturer in Human Resource Management and Public Policy at Leeds University Business School.

Image: Nick Youngson CC BY-SA 3.0