Verena K. Brändle, Charlotte Galpin, Hans-Jörg Trenz

Since the referendum in June 2016, a new phenomenon of bottom-up, self-organized pro-EU mobilisation has appeared in the UK. In the days following the referendum new initiatives and groups emerged to represent the voices of the ‘48%’ who voted to remain in the EU. Instead of relying on established party structures and media, anti-Brexiters self-organise on social media. New Facebook pages or Twitter campaigns are used to reach out but also to network between local and regional pro-EU groups and to organise campaign activities such as street stalls, family days, public meetings, and rallies. In coordination on a regional and national level, these groups have organised a number of large anti-Brexit marches in London and other cities around the UK.

In this article, we explore pro-European mobilisation in the UK as an emotional counter-reaction to populist discourse during Brexit and its claim of a unitary representation of the sovereign ‘will of the people’. Pro-European protest is triggered as an emotional response by those who feel excluded from popular and homogenous conceptions of ‘the people’. From the perspective of these excluded minorities Brexit is experienced as bereavement. Their emotional responses and the coping strategies they develop are a case of anti-populist counter-mobilisation against the broader public debates in the aftermath of the referendum.

Public debates about Brexit have continually referred to the need to implement the ‘will of the people’. At her first Conservative Party conference after the referendum, Theresa May declared that ‘Parliament put the decision to leave or remain inside the EU in the hands of the people. And the people gave their answer with emphatic clarity.’ In reference to those calling for a parliamentary vote on the trigger of Article 50, she claimed that they ‘are not standing up for democracy, they’re trying to subvert it…They are insulting the intelligence of the British people’. Similarly, headlines in the Eurosceptic British press have contributed to this definition of the British. The Daily Mail, for example, declared the Supreme Court judges who confirmed Parliament’s role in triggering Article 50 were the ‘enemies of the people’. The Telegraph has even described parliament as attempting to ‘subvert the will of the people’.

Brexiters draw here on a particular discursive and stylistic repertoire which can be characterised as populism. It is a form of populism that extends beyond the strategy of particular parties and encompasses government, Parliament and the media, shaping public conceptions of belonging. Declaring 52% of votes for Brexit as ‘the will of the people’ is an imposition of the sovereignty of the people that undermines the core principles of Westminster parliamentary democracy as popular will-formation through the mediation of plural interests. Such calls thus bypass traditional means of reconciling class conflicts and balancing the many social and ethnic cleavages which make up British society. Plebiscites are therefore not just poor substitutes of parliamentary representation; they result, de facto, in misrepresentation, in this case, of the 48% who are silenced and whose transnational lives and sense of multiple belonging in Europe are rendered invisible. The populist demarcation of ‘the people’ as a homogenous and unified group is thus experienced by the excluded as an injustice resulting from misrecognition and misrepresentation and triggers an emotional counter-reaction.

The study of populism thus also requires a focus on the perspective of the represented or non-represented, that is, from the ‘bottom up’. We do not only need to denounce the populist styles and rhetoric as a form of misrepresentation, but we also need to turn our attention to the ways the sovereign expression of the will of the people is experienced by the silenced minorities (in the plural!) as being fundamentally unjust and threatening their alternative life projects and identities.

Emotional processes such as anger and resentment have been identified as playing a critical role in the motivation of voters to support populism. Through the Brexit campaigns, resentment is often expressed aggressively towards others who supposedly differ fundamentally in values, attitudes and lifestyles. The mobilisation of such unitary conceptions of the people is highly asymmetrical, facilitated by the structures of the public sphere. Dominant narratives of popular sovereignty in Britain have always historically drawn a binary distinction between Britain and Europe, where Europe is ‘“the Continent”, over the Channel, a place to which Britons go rather than belong’. Those who defend such positions are thus systematically rewarded with high media salience. The British media have been a key driver of the populist Brexit discourse with especially Eurosceptic newspapers exercising ‘destructive dissent’ in their reporting of the EU.

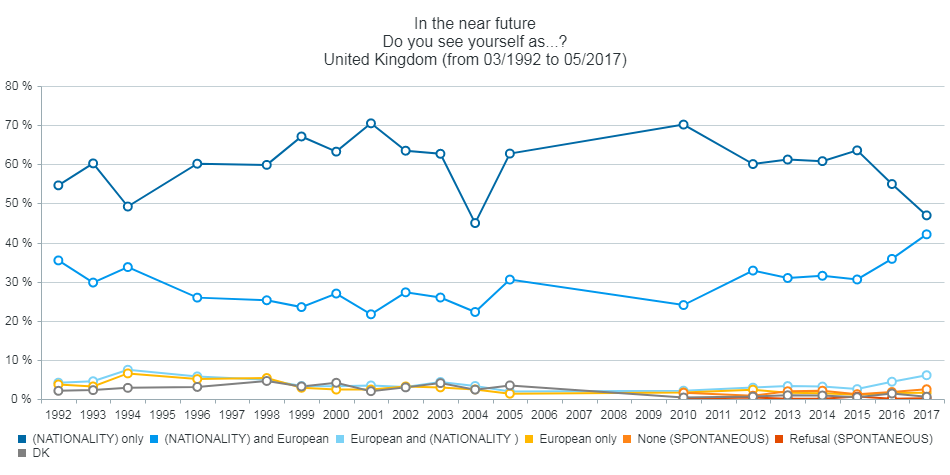

This asymmetry in the discursive constellation of the British public sphere consequently marginalises the voices of those who defend multiple belongings and/or identify politically or culturally as European, leaving them in a structurally disadvantageous position. This is an especially severe consequence of populist claims since for most British people, questions of identity and belonging are experienced in a much more diffuse and ambivalent way. In fact, recent Eurobarometer data show a picture of rather multi-layered identities in the UK. Most significantly, this number of people who identify as both British and European has increased after the Brexit referendum, reaching 48% in 2017 – its highest level since 1992. In other words, many people in the UK do not adhere to the more simplistic definitions of “the people” in the nationalistic sense, as is often the case in populist repertoires.

In our survey of participants on London’s March for Europe in March 2017, participants expressed a collective attachment to their European identity, EU citizenship, and concern for the future of the UK – their home, whether adopted or by birth. What is particularly striking is a feeling of grief that is linked explicitly to the loss of a European identity or cosmopolitan British identity. Many likened Brexit to a bereavement, to heartbreak, to a kind of violence being done to them: as one participant reported, ‘I feel European to my core, yet I am having this essential part of my identity torn from me and from my children’. Brexit understood as bereavement thus shows how mobilising against Brexit is rooted in feelings of fear and grief over the loss of EU citizenship and plural ways of identifying as UK citizens or residents within the EU. The binary distinctions inherent in populist discourse make invisible these intertwined, transnational identities of many in the UK with European lives, who do not – and cannot – clearly delineate their sense of belonging. They also render forgotten the legitimate concerns of the many people who depend on EU citizenship and for whom ‘leaving’ becomes an existential threat.

At the same time, it seems that by taking away the EU as a frame of reference, protesters feel alienated from the country and the political process. Not only does Brexit develop into an injustice because it takes away legal status, rights and a frame of reference for belonging and identity, it also brings the legitimacy of the UK political system and its new national boundaries into question. Many people express not just a sense of disenfranchisement, of being ignored by parliament and the government, but a new inability to identify as British, a ‘profound shame’ associated with the perception of a fundamental shift in values away from multiculturalism, tolerance and openness to the world.

It is thus noticeable how Brexit as a case of bereavement and Brexit as a case of misrepresentation are intrinsically related. The imposition of the sovereign will of the people triggers an exclusionary mechanism against a multitude of people, individuals and collectives both within and outside the country whose interests and whose identities can no longer be accommodated. What follows from this is the necessity to consider Brexit not only as a political decision within the UK but as an instance of injustice linking personal grievances with supranational questions of representation and recognition.

A ‘bottom-up’ perspective thus emphasises these people’s enactment of grief and how it manifests in justice struggles over representation beyond the nation-state. Our research demonstrates that ‘the 48%’ are mobilising directly against such exclusive and unitary definitions of the British people. Such mobilisation has brought together a heterogeneous group of those holding only British nationality, dual citizenship, other EU citizenships and non-EU citizens collectively as the ‘48%’, ‘Remainers’, ‘Remoaners’, ‘saboteurs’ – the latter two references to the tabloids’ calls to ‘crush the saboteurs’ of Brexit, labels that have since been reclaimed by pro-EU campaigners who wear them – literally – as a badge of honour. Anti-populist counter-mobilisation is therefore not just a matter for people with a certain legal status and rights but cuts across the boundaries drawn by populist claims, bringing together people who share feelings of grief and injustice over Brexit and its consequences.

The anti-Brexit marches highlight how the UK’s withdrawal from the EU is experienced by those people who, by protesting and speaking up against Brexit, aim to become visible again and reclaim their multi-layered identities. Anti-Brexit campaigners thus develop their own anti-populist style of emotional mobilisation by using placards and slogans to emphasise the inclusiveness and multi-layered nature of their identities. On the marches, protesters construct their own version of Britishness which is open and tolerant (one placard asks, “aren’t we all immigrants?”). Protesters also publicly demand recognition of their multiple identities with slogans such as “Britain belongs in EUrope”, and “Born UK, Born EU”. They often unite key symbols of Britishness – such as Winston Churchill and Shakespeare – with Europe, using quotes and imagery. The demonstrations thus function as a creative expression of an inclusive or European British identity to counter the exclusive populist style of the Brexiters.

Ultimately, we argue that the pro-European mobilisation against Brexit has a highly personal and emotional trigger: It concerns the grief people express over the loss of EU citizenship rights and transnational, European belonging. This expressed grief is remarkable given that citizens’ identifications with the EU or Europe in public opinion surveys have, until recently, so far remained rather weak. A focus on how people enact their grief from the bottom up sheds light on how people perceive, experience and react to populist discourses. In this way, it makes visible the various minorities populism creates. Prior to the referendum, those excluded from the public discourse nevertheless held the status of EU citizen, had access to the rights and opportunities afforded by EU citizenship, and could live and plan a transnational, European future. Post-referendum, these opportunities and recognised identities appear to dissipate. Brexit thus becomes a moment of resistance, in which the mainstream populist style of unitary representation of the people is countered with forms of enactment of citizenship that open alternative imaginations and broaden the space of political representation trying to forge new narratives of European belonging in Britain.

Verena K. Brändle is a postdoc in the Department of Media, Cognition and Communication at the University of Copenhagen. Charlotte Galpin is Lecturer in German and European Politics at the University of Birmingham. Hans-Jörg Trenz is Professor for Modern European Studies in the Department of Media, Cognition and Communication at the University of Copenhagen and ARENA, University of Oslo.

Image Credit: Jens Roesner