Richard Johnson

In spite of sanguine predictions made at the beginning of his presidency, Barack Obama’s tenure in the White House has not coincided with improvements in public attitudes on race or material gains for most African Americans. Commentators have been perplexed by the apparent incongruity of the election and re-election of an African American president amidst stark and in some cases increasing racial divisions in American society.

Most visibly, the Obama presidency has been marked by confrontations between America’s impoverished black citizens and white power figures, particularly the police. The statistics bear out a grim picture. Under the Obama presidency, the chance that a young African American man will be shot dead by the police is twenty-one times greater than it is for a young white man. While blacks make up 14% of the US population, they constitute 44% of all murder victims, 38% of the US prison population, and 58% of youth admitted to state prisons.

In his new book, Governing with Words, Daniel Gillion (2016) places some of the blame with Obama’s silence on race. Gillion finds that Barack Obama has mentioned race in public speeches fewer times than any post-war Democratic president. For Gillion and others, this apparently deracialised governing strategy represents little more than a betrayal of the African American electorate. Fredrick Harris (2012) has lamented that the ‘price’ of a black president was his silence on racial inequality. Various commentators have called it the ‘paradox of the first black president’.

Gillion’s work has received much attention, but there are several factors which go against the conclusion that Obama himself is culpable. Instead, Obama’s racial ‘silence’ must be understood in the context of an unprecedented, intense racialisation which has characterised American perceptions of public policy in the Obama era.

Spillover of Racialisation

First, the methodological approach Gillion has chosen should be questioned. Gillion measures the frequency by which presidents mention race in their public speeches. Gillion supposes that race becomes salient when a president speaks explicitly about the racial implications of a policy. This can have important positive implications for communities of colour. For example, when Bill Clinton spoke about the particular health challenges faced by African Americans, reporting about health increased in historically black publications.

The problem with Gillion’s approach is that, when it comes to race, Obama simply cannot be compared to his predecessors. Unlike other presidents, Obama has not needed to speak about race explicitly for his policies to be interpreted in racial terms.

As Michael Tesler (2016) has shown, Obama’s racial significance, coupled with the tendency of voters to associate policies strongly with the presidents who support them, has led voters to evaluate policies associated with Obama through a racial frame. The ‘spillover’ of racialisation has been recorded in the past when racial attitudes and race are brought to bear on political preferences, such as associating welfare with undeserving blacks (Gilens 1999) and Social Security with hard-working whites (Winter 2006). Usually such racialisation is the consequence of priming by political actors and the media, or the result of entrenched historical associations. But, for Obama, policies and people with no manifest racial content quickly become racialised.

For example, reactions to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) differ sharply by race, with 91% of African Americans supporting the healthcare legislation, compared to only 29% of whites. However, among whites, the likelihood of approval for provisions in the ACA corresponds closely to a person’s attitudes on race. This is not merely a question of partisanship. Tesler found that decline in support for a ‘public option’ fell almost twice as quickly among racially resentful whites when told it was a policy proposed by Barack Obama rather than a policy proposed by Bill Clinton.

Even mundane associations, such as a pet dog, have been shown to be affected by the racial spillover. Racially resentful whites were more than twice as likely to react negatively to the photo of a dog when told it was dog which belonged to Barack Obama than when told it was a dog which belonged to Ted Kennedy.

In answer to Gillion’s ‘governing with words’ thesis, the simple fact is that President Obama has raised the salience of race – often without words.

Racially Polarised Partisanship

A second shortcoming of Gillion’s work is his limited account of the growing convergence of racial attitudes and partisanship. For example, one of Gillion’s contentions is that when presidents speak about race, congressional leaders are more inclined to support the passage of racially targeted policies. The implication from this is that if Obama spoke more about race, we should expect Congress to pass more race-conscious legislation.

Setting aside the first two years of his presidency, when his efforts were focused on the passage of the fiscal stimulus and healthcare reform, Obama has faced at least one Republican-controlled chamber in the federal legislature. However, is doubtful that racialised language from Obama would persuade a Republican-controlled Congress to pass more racially targeted legislation.

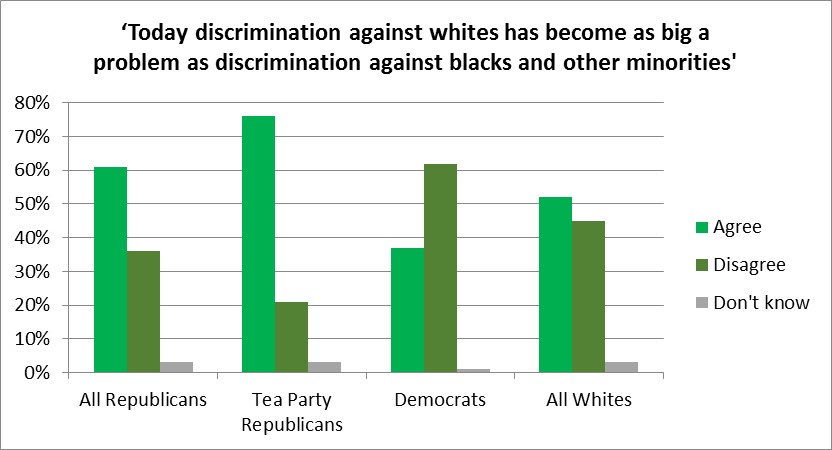

The Republican Party now represents a white electorate who does not even recognise black deprivation, let alone agrees on whether such conditions should be alleviated using race-targeted or universalist policies. Overall, more than half of white Americans feel that racial discrimination against whites is at least as big a problem as racial discrimination against African Americans. More than three-fifths of Republicans and three-quarters of Tea Partiers feel that whites face at least as much discrimination as blacks.

Figure 1. Whites’ perceptions of racial discrimination

Source: PPRI American Values Survey, 2014

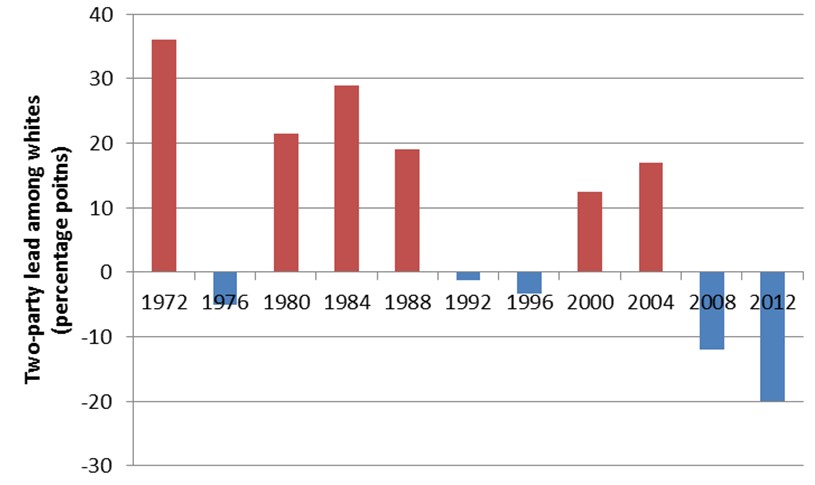

Democrats, including President Obama, are less inclined to listen to these views, as they become decreasingly less dependent on whites for electoral success. While the Democrats have trailed Republicans in white presidential support for the past forty years, previous Democratic candidates won the presidency when they narrowed their gap in white two-party support to a deficit of five percentage points or less. Obama is exceptional in having won the presidency with a double-digit deficit in white support (in both elections). In fact, no president has hitherto been elected to the White House with as small a proportion of the white two-party vote as Barack Obama.

Figure 2. Two-party lead/deficit among whites by winning presidential candidate, 1972-2012

Source: Presidential exit polls, 1972-2012

Structural Constraints of the Presidency

A third shortcoming of Gillion’s account is its failure to take structural constraints on the presidency seriously. Gillion asserts without qualification that when presidents speak about race ‘they set the agenda’ and ‘force’ the other branches of government to engage with the issue. Such confidence in the power of the presidential bully pulpit runs contrary to empirical research conducted by George Edwards (2003) which shows that presidents, in fact, have very weak capacity to shift opinion and set the political agenda.

Gillion’s evidence is, in part, based on widespread but ultimately unsubstantiated political folklore. For example, he simply takes for granted that Franklin Roosevelt’s fireside chats ‘swayed’ the American public and ‘assuaged citizens’ fears’. This may have been Roosevelt’s intention, but Gillion cites no empirical evidence to show that these chats independently achieved such a function.

In fact, the president’s independent capacity to reduce racial inequalities are highly constrained. While Americans have high expectations for their president, it is an office which, as Richard Neustadt (1991) famously wrote, is characterised by profound weakness. While many accounts have focused on Obama’s personal ability to accomplish racial change, most compelling social science research points to impersonal structural forces, including federalism and partisan control of Congress, as explaining presidential impact.

Conclusion

In spite of the failure of Barack Obama to reduce material white-black inequality, African Americans have been the most supportive constituency throughout his presidency. Obama’s approval rating among blacks sits between 85-90%, while with whites it ranges 30-40%. Relatedly, in spite of their worse relative and absolute economic conditions, African Americans are more optimistic about their economic futures under the Obama years than they have been under previous presidencies. Even on racial policy, a June 2015 poll found that 84% of blacks approved of the job Obama was doing on race relations, compared to only 48% of whites.

It may be that African Americans have become more realistic about presidential capabilities than most other Americans tend to be. They approve of the president not because they think he has done enough but because they know he can do so little. Anthea Butler explains that particularly for older African Americans, their attitude towards the president is, ‘Honestly, we just want him to get out alive’.

References:

Edwards, George. 2003. On Deaf Ears. Yale University Press.

Gilens, Martin. 1999. Why Americans Hate Welfare. University of Chicago Press.

Gillion, Daniel. 2016. Governing with Words. Cambridge University Press.

Harris, Fredrick. 2012. The Price of the Ticket. Oxford University Press.

Neustadt, Richard. 1991. Presidential Power and the Modern Presidents. Free Press.

Tesler, Michael. 2016. Post Racial or Most Racial? University of Chicago Press.

Winter, Nicholas. 2006. Beyond Welfare. University of Virginia Press.

Richard Johnson holds a BA in SPS from Cambridge University and an MPhil in Politics from Oxford University. He is presently a doctoral student in political science at the University of Oxford, and visiting student at Yale during 2016-17, completing a thesis on black representation and electoral politics in the US.

Image: Quinn Dombrowski. CC BY-SA 2.0