Peter Beresford

All Our Welfare sets out to combine an academic analysis of the welfare state, past, present and future, with an exploration of it in relation to my own family. What has been revealing for me is how each has offered insights into the other. Especially worrying are the implications of the present direction of travel of the welfare state, highlighted by the particular circumstances of my own unusual family background.

All Our Welfare draws on both research evidence and the experiential knowledge of people on the receiving end of welfare. A powerful narrative that is used to justify the restructuring and reform of welfare has been that it might have been helpful once, but it is now a much less appropriate anachronism. We are told that demographics and social conditions have changed and the welfare state has proved itself wasteful and a drag on wealth creation, leading to dependency and abuse. However this conventional wisdom demands to be subjected to be more critical inquiry and this is what I sought to do.

An understanding of history tends to be an early casualty in discussions of welfare reform. It is important to be aware that most, if not all, the conflicting positions on the welfare state that have become significant over the last 30 and more years can be seen as already in place, even before the Labour government that created the welfare state came to power. F.A. Hayek, at the London School of Economics, was writing The Road to Serfdom, his defence of classic liberalism and attack on socialism in 1944 (Hayek, 1944), just months before Michael Young was penning the Labour Party’s 1945 manifesto, Let Us face the Future, Winston Churchill enlisted Hayek’s book as part of his disastrous 1945 election campaign attacking Labour’s ‘state socialism’. Hayek was a key influence on Mrs Thatcher, who later wrote of repeatedly reading this book from the late 1940s onwards.

We should remind ourselves, that if she had been able to, Mrs Thatcher would have imposed Thatcherism after the war, rather than using the supposed failure of the welfare state as her argument for introducing neo-liberalism 30 years later. What this suggests is that the underpinning issue is not about a growing disillusionment with the form the welfare state ultimately took, as we are often told, but an inherent opposition to its aims and philosophy from the start, even before it came into existence. Left to those who have subsequently opposed it, there would never have been a welfare state!

If there was some level of political consensus about the welfare state until the 1970s, it is doubtful whether there was ever the same ‘public consensus’. There was no unanimity about the setting up of the welfare state. Divisions seemed particularly to relate to people’s class, status and politics. The creation of the welfare state had challenged many people’s fears that life post second world war would be the same as after the great war; a world of poverty, depression and insecurity. But for the more advantaged, the welfare state could seem like an extension of war time state controls, with higher taxes, more restrictions and less privilege. The Conservative election victory of 1951 was seen as a victory for the middle classes, who repeatedly expressed their irritation with what they saw as the constraints and regulation of the previous government. This despite a point repeatedly made that they particularly benefitted from the National Health Service and from Labour’s later ending of the 11 plus education selection system (Le Grand, 1982).

From the mid 1970s, with the political shift to the right, politicians and an increasingly powerful right wing media have sought to enlist working people as a stage army to support their anti-welfare state policies. They have done this by feeding them a diet of welfare benefits waste and abuse. They have reframed the welfare state as synonymous with the benefits system and exaggerated the public cost of abuse, while more often ignoring the much greater cost to the public purse of tax avoidance and evasion by the better off.

Opposition to the welfare state is rooted strongly in division and inequality. Perhaps not surprisingly my family background highlights both the reality and the damaging consequences of such inequality and impoverishment that results from it.

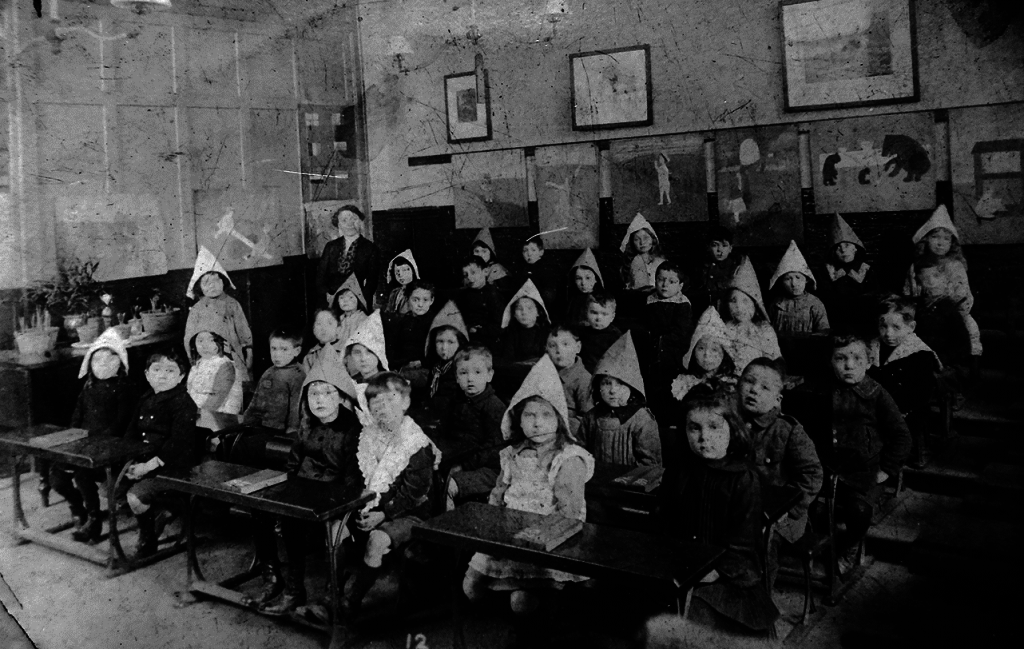

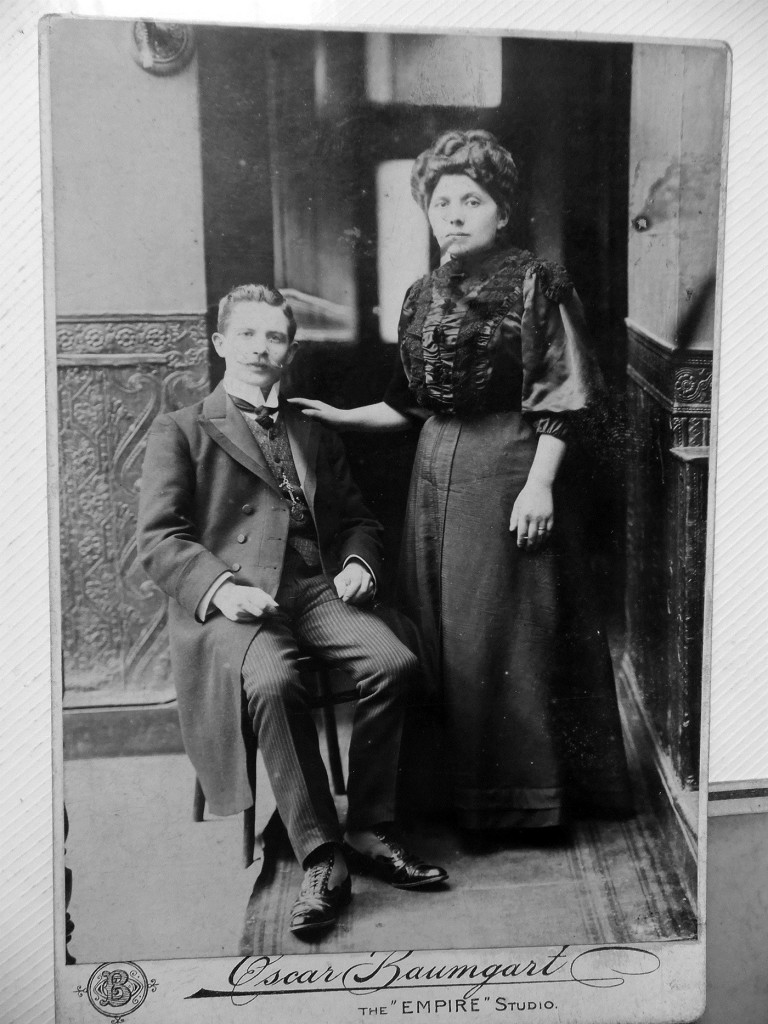

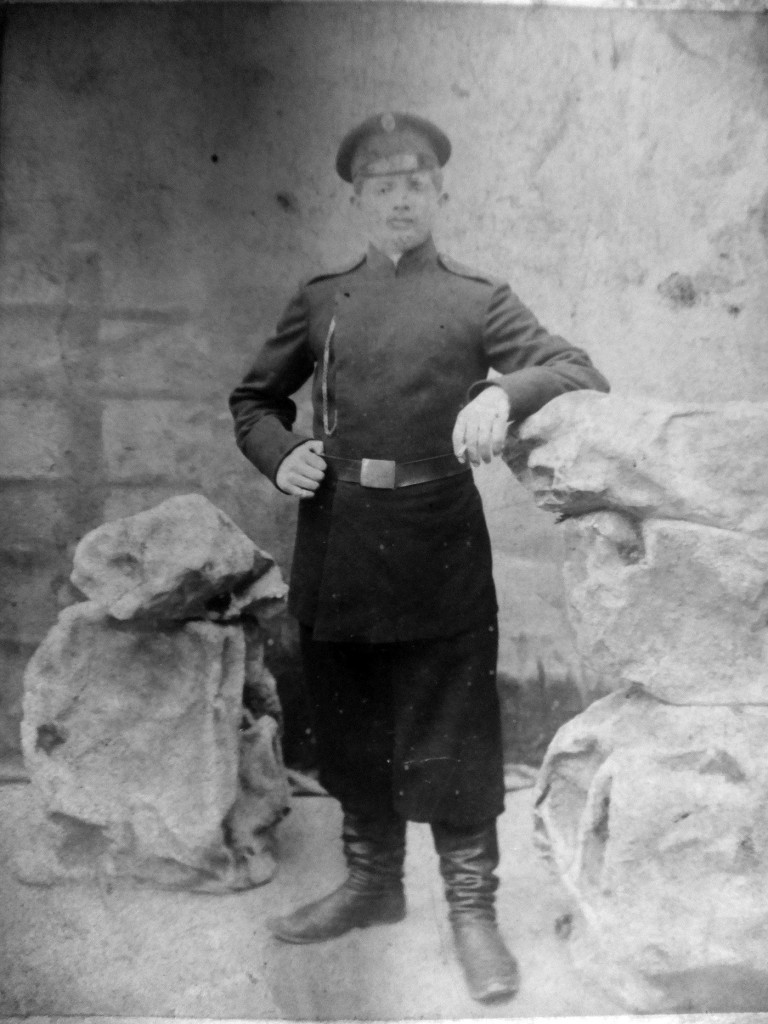

My biography is an unusual one. I have often found it difficult to think of two parents so far removed from each other as mine. My mother was the daughter of immigrant Jews who had fled murder and rape in Eastern Europe. They lived in Russian occupied Poland and my grandfather served in the Imperial Russian army as a conscript and worked all his life as a tailor. They came to Britain at the turn of the twentieth century in the wake of one of the appalling anti-Jewish pogroms then taking place. They came as immigrants and ‘asylum seekers’, with nothing. My grandmother never learned to speak English. My mother left school at 14, living in poverty as a child and then working in sweat shops as a milliner.

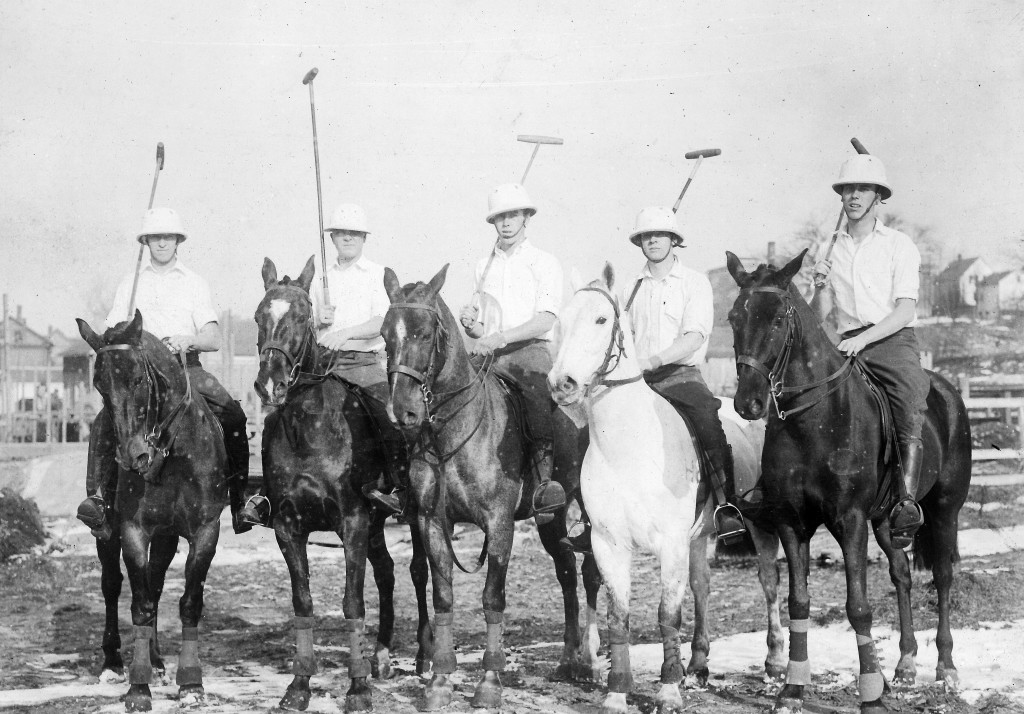

My father, on the other hand came from an aristocratic family, was the son of a lord and was much older than my mother. His family represented a very different kind of immigrant, coming with the Normans. His documents described his occupation as ‘of independent means’. My mother would never tell us how they met.

My father died when I was four and so I was brought up, along with my sister, up by my mother. The key influences in our childhood came from my Jewish working class background, not the upper class wealth and opportunities that had existed in my father’s family.

Looking back I have a sense of pride in what it has been possible for me to achieve in my mother’s parents’ adopted country. I got a grant to go to Oxford University, I became a professor and received an OBE from the Queen. If they had lived long enough to witness this, it would have been a fairy story for my grandparents Barnet and Dora. I am proud of what I have achieved. But don’t think any of this would have been possible without the British welfare state and the values associated with its foundation: universalism, redistribution, social mobility, social justice and increased equality. More to the point, increasingly I wonder if any of this would be possible if I were to be starting again now. And sadly I think the answer is probably no.

I think having this strange mixture of parents is one reason why I have always found the snobbery, class consciousness and discrimination that have long characterised England, particularly unpleasant. Their influence can be seen as a powerful thread running through the history of the welfare state and its antecedents and sadly still seems powerful today. In the past the talk was of ‘outcasts’ and the ‘residuum’; now it is of ‘skivers’, ‘scroungers’ and ‘Benefits Street’. ‘Public opinion’ about welfare has been mercilessly groomed by those advancing the prevailing neo-liberal political and media agenda. We are fed fantasies of Downton Abbey, apparently unable to appreciate what the contemporary reality was; gross levels of health inequality, minimal social mobility and equality of opportunity, damaging degrees of poverty and want. We seem to be running headlong back to such a world, with current welfare state reform, returning to much greater inequality reduced social mobility, greater division and poverty.

When I look at my family photographs and some of the extremes of inequality they highlight from the past, it increasingly feels to me that we are coming full circle, with poverty, social division and inequality on the rise again. This is an indictment of the direction our society has taken. It is also a strong recommendation for the welfare state and its founding values. Of course they were not perfect and pioneers since then have addressed key omissions of participation, inclusion and diversity. It is these that offer the possibility of an alternative to the present ‘welfare reform’ narrative and hope for the future.

References:

Hayek, F.A. (1944), The Road To Serfdom, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press.

Le Grand, J. (1982), The Strategy Of Equality: Redistribution and the social services, London, George Allen and Unwin.

Beresford, P. (2016), All Our Welfare: Towards participatory social policy, Bristol, Policy Press.

Peter Beresford is Professor of Citizen Participation at the University of Essex and Emeritus Professor of Social Policy at Brunel University London

Image: Peter’s grandaughter