Roger Burrows, Goldsmiths University of London [pdf]

In his classic account of The Age of Uncertainty, the great political economist JK Galbraith observed that: ‘Of all the classes, the wealthy are the most noticed and least studied.’ Some 36 years on might this, at last, be changing? Certainly, the question of where the ‘super-rich’ live is now firmly on the agenda, and there is a renewed interest in the sociology of elites and the ‘geodemoraphics’ of their social composition and location.[1] At last, perhaps, popular cultural and journalist interests in the fortunes and actions of the rich and powerful are being matched by contributions from the social sciences.

Are there other sources of knowledge about the ‘tiny, stratospheric apex that owns most of the world’[2] that we could be drawing upon? Certainly publications from the commercial sector, from the likes of Capgemini, Forbes and Frank Knight, are widely utilised in the extant social scientific literature. The most recent World Wealth Report, for 2013, from Capgemini, certainly makes for interesting reading. It calculates that there were 12.0 million High Net Worth Individuals (HNWIs) – each with $1m or more of investable assets – around the globe in 2012. Of these it was estimated that some 465,000 were resident in the UK (up from 441,000 in 2011).

But what if we want a clearer view of where and how the rich live today? As Savage and Williams point out, traditional survey research is of little use in this regard because of the closed patterns of life among the wealthy – we are unlikely to gain insights by asking direct questions about their income and even less likely to successfully use such techniques to measure their wealth. But what of other methodological innovations resulting from the increasing ubiquity of digital data?[3] What about the supposed turn to big data? Are the super-rich able to circumnavigate the statistical gaze of, for example, the commercial geodemographics industry – systems such as ACORN and MOSAIC – that seem so ably to classify and precisely locate the rest of us?

ACORN, MOSAIC and a cluster of other such systems geocode every address in the UK based upon a huge amount of spatially referenced data sourced from myriad commercial and official sources. The current MOSAIC system, owned by Experian, holds over 400 items of data on almost 49 million adults in the UK. These adults can then be associated with individual addresses. There is not always a one-to-one correspondence between a person and an address however, as some people are ‘associated’ with more than one address – students, people with two or more homes, and so on.

The nature of the ‘association’ may also vary – it could be voter registration, responsibility for payment of a utility bill, a mobile phone or some other account. However, the data does broadly allow each address in the UK to be classified in relation to the types of adults ‘associated’ with it. The MOSAIC system classifies each address into one of 67 different types, whilst the ACORN system classifies them into 62. The statistical procedures that each uses to cluster and then classify each address is, of course proprietary.

Although the veracity of the classifications are not primarily driven by sociological sensibilities, they ‘work’ in the sense that they identify highly nuanced differences between neighbourhoods that have proven useful to a wide range of commercial, public sector and other agencies. What do such systems offer if we are keen to identify the socio-spatial characteristics of, for example, HNWIs? Certainly debates about wealth, inequality and the changing nature of urban life deriving from massive house price rises offer good reasons for thinking about and locating the wealth in social spaces across urban systems such as London and other cities.

For ACORN, addresses most likely to be associated with such people are grouped together as ‘Lavish Lifestyles’, which are further differentiated into: ‘Exclusive Enclaves’; ‘Metropolitan Money’; or ‘Large House Luxury’. For those taking their cues from Bourdieusian notions of social capital, the MOSAIC system might appear to offer advantages given its classification of the wealthy into a type of space labelled as part of the ‘Alpha Territory’ of which there are considered to four distinct types: ‘Global Power Brokers’ (GPB); ‘Voices of Authority’ (VA); ‘Business Class’ (BC); and ‘Serious Money’ (SM).

The 465,000 HNWIs we started with in the UK are most likely to be ‘associated’ with addresses located within this ‘Alpha Territory’ (AT); however they are most likely to be found in postcode areas classified as Global Power Brokers than in the other three types. Across the UK as a whole we can locate some 1,759,984 adults associated with addresses in the AT but, within this category, only 144,553 are located in GPB areas. If we are interested in the geodemographics of the ‘super-rich’, then the GPB addresses might be thought of as offering us the most intense concentrations of such people, whilst a focus on the Alpha Territory (AT) as a whole gives a broader indication of where they might reside.

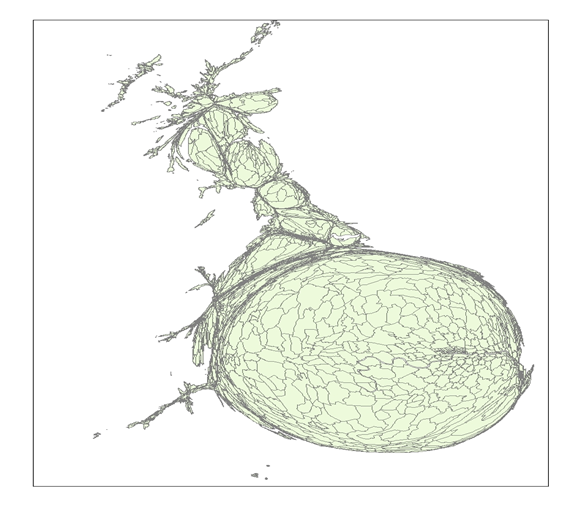

Amongst the AT as a whole, some 60.7 per cent live in London or the South East. To illustrate this if we draw a map of the UK not in relation to land mass but, instead in proportion to the distribution of the AT addresses (a cartogram) and this is what it looks like:

Such a map would be close to impossible to draw if we were to focus only on the distribution of GPBs since they are overwhelmingly (95.2 per cent) located in London. Not surprisingly the distribution of GPB addresses within London is itself unevenly distributed across the capital. The highest concentration can be found in London W8 – Kensington – where some 58 per cent of adults are so classified, next comes SW3 – Chelsea – where the figure is 56.6 per cent – and third comes SW7 – South Kensington where almost 51 per cent are so classified. In these three areas the majority of addresses are associated with some of the wealthiest people in the world.

But the percentage figures are a little misleading if we are interested in raw numbers. The largest number of GPBs – some 14,018 – live in Belgravia, but the size and demographics of that area are such that they constitute just under 30 per cent of the population. All of this shows that we need to be aware of both the absolute and relative size of these groups when we begin to think about the relative presence and influence of the wealthy in a city like London.

Not surprisingly, the kind of geodemographic distributions we are describing here are highly spatially correlated with house prices. A recent report found that ‘an astonishing £83bn of properties were purchased in 2012 with no financing – all cash purchases’ in these ‘super prime’ property market areas. According to property analysts Knight Frank, although about one-third of ‘super-prime’ (properties selling for £10m or more) buyers were from the UK, between 2010 and 2012 two-thirds of purchasers were from overseas: 19 per cent from Russia; 15 per cent from the middle East; and 10 per cent each from Asia-Pacific and Europe.

Such figures highlight the emerging social geography and global forces of capital accumulation that are now re-shaping even those areas in London that have been historically some of the most fashionable and elite areas of that city. What we have here is an astonishing concentration of global wealth not just in London but in very specific and highly circumscribed enclaves within it. Geodemographic data of the type described here highlights how the city is changing and allows us to throw light on those social groups who have traditionally been absent from social research because they are so difficult to locate and access.

These neighbourhoods of extraordinary wealth concentration offer social researchers exciting and important opportunities for analysis and reflection. The kind of gilded ghettos we are describing are beginning to be identified in newspaper articles and political debates, about London and its housing system, as a social problem. If these were areas of concentrated poverty they would be considered a significant social problem, yet it is increasingly clear that such areas and the global growth of money power that underpin their emergence are already beginning to exercise policy makers and the lay public and social researchers require eclectic and innovative means of responding to these concerns. A situation of massive cuts to public spending and reductions in support for those on low incomes and their housing is occurring side-by-side with unchecked gains for the wealthiest.

References:

[2] Hay, I. and Muller, S. (2012) ‘“That Tiny, Stratospheric Apex That Owns Most of the World’ – Exploring Geographies of the Super-Rich’, Geographical Research, 50, 1, 75–88.

[3] Burrows, R. and Savage, M. (2007) ‘The Coming Crisis of Empirical Sociology’, Sociology, 41, 5, 885-899.

Roger Burrows is Professor of Sociology and Pro-Warden for Interdisciplinary Development at Goldsmiths, University of London. He has longstanding research interests in urban studies, digital media and sociological research methods.