Image from the Ordinary Streets Project, LSE Cities, 2012

Suzanne Hall, LSE [pdf]

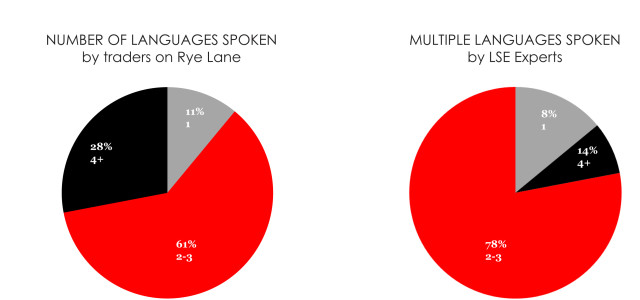

On the ‘Research and Expertise’ webpages of my university, the language proficiencies of its scholars are highlighted at the top of each individual resume. Language fluencies are listed upfront to signal an ability to interact with individuals, geographies and ideas beyond one’s own origins. A brief analysis of the language proficiencies listed in the ‘LSE Experts Directory’ in 2012 indicates connections between scholarship, multilingualism and exchange in a fluid world: 8% of university experts were conversant in one language; 78% were conversant in two to three languages; and 14% in four languages or more. The status value of language and communication is plainly stated as a skill; an acquired expertise in international forms of engagement. It is difficult to imagine contexts in which multilingual competencies are not celebrated as desirable, even necessary, skills for navigating the cultural and ethnic diversities integral to our twenty-first century.

However, our fluid world is also a highly disparate one. Hierarchies of numerous kinds prejudicially rank the practices of engagement and adaptability integral to speaking outside of a mother tongue. Language is a both a signifier and mode of belonging, and in the rising acrimony of migration-speak across the UK and Europe, language is frequently invoked as a symbol of preservation, rather than communication. In the inimitable words of the Right Honourable Theresa May, Home Secretary of the UK:

“With annual migration still at 183,000 we have a way to go to achieve my ambition to reduce that number to the tens of thousands […] In particular, I want to talk about measures we’re taking to make us more discerning when it comes to stopping the wrong people from coming here, and even more welcoming to the people we do want to come here […] It takes time to establish the personal relationships, the family ties, the social bonds that turn the place where you live into a real community. But the pace of change brought by mass immigration makes those things impossible to achieve. You only have to look at London, where almost half of all primary school children speak English as a second language, to see the challenges we now face in our country.” (Home Office speech 2012):

The Home Secretary voices concern for an accelerated process of migration. Indeed, the 2011 Census evidences an increase in the extent and variation of the ‘country of birth’ category in England and Wales: 12% of the population were born outside its borders, and 173 out of the world’s 229 nations now have at least 1000 residents in England and Wales (Paccoud 2013). Alongside long-established histories of migration and the ever-paradoxical categorisation of the ‘first/second/third generation immigrant’ in the UK, are reorientations within ethnic and racial categories. One in five individuals living in England and Wales identifies themselves as other than ‘White British’ and there has been a substantial increase in individuals identifying with the ‘Mixed’ or ‘Other’ ethnic categories (CoDE 2012).

It is the Home Secretary’s view that migration compromises social bonds and local communities. Multilingualism in London schools – specifically speaking English as a second language – is perceived as an outright challenge to the process of learning and to the costs of educating. Undoubtedly, the diversifying societies that will be increasingly integral to twenty-first century life and politics will require different approaches to how citizens are resourced and how they learn and keep apace, both inside and outside of institutions. Being socially agile in a fluid and disparate world requires redefinitions of citizenship and exchange. What then, might we learn from the practice of language, specifically multilingualism, as a constitutive of expression, communication and belonging?

By way of contrast with the university, let’s turn to the street. In 2012 a multidisciplinary team of architects and sociologists, whose origins spanned South Africa, Santiago and the US, undertook a survey of a multi-ethnic street in a comparatively deprived urban locality . Rye Lane in Peckham south London is a kilometre stretch of densely packed retail activity. One hundred and ninety-nine retail units line the street edges, two-thirds of which are independent shops that are occupied by proprietors from over twenty different countries of origin, including: Afghanistan, England, Eritrea, Ghana, India, Ireland, Iran, Iraq, Jamaica, Pakistan, Kashmir, Kenya, Nepal, Nigeria, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, Uganda, Vietnam and Yemen. In the absence of an ‘expertise directory’ for the street, we asked the proprietors to name the languages they spoke: 11% of street proprietors spoke one language; 61% spoke two to three languages; and 28% spoke four languages or more. The language proficiencies of proprietors on Rye Lane are as remarkable as those of the LSE experts, and in the proficiency category of four or more languages, the street excels.

What do the street proprietors use language for? The repertoires of multilingual communication are as strategic as they are sociable, and activate opportunism, solidarity, exchange and aspiration. Multilingual competencies on the street are more than simply verbal; they allow for new forms of transaction and enterprise. One in four of the shops along Rye Lane practice a form of urban mutualism: a subdivision and subletting of space into small interdependent parts and activities, across ethnicity, origin and gender. Within one shop space, ‘Armagan’ who recently arrived from Afghanistan, occupies two square metres of space at the front of the store where he trades in mobile phones and software services. ‘Umesh’ who arrived from Uganda in 2003, runs a Western Union remittance store at the back of the shop. We ask Umesh who his customers are, and he replies, ‘All kinds of people, sending money to their countries, and changing money for travel. They are all ages, from everywhere – Africa, Europe, Asia, everywhere’. ‘Frances’ is from Ghana, and her space is allocated between the two micro-shops at the front and rear, leaving just enough room to stack rolls of cloth and accommodate her sewing machine. Together they must negotiate how toilets are shared, and how security is arranged. Within the shop interior, they share risk and prospect, and shape the textures and spaces of a multilingual street economy.

Sociolingual writers like Jan Blommaert and Ben Rampton remind us that language is both circumstance and ability. Fluency in multiple languages therefore emerges as much in the circuits of displacement imposed by migration, as it does within the elite world of universities. ‘Aahad’, for example, has traded on Rye Lane for 32 years. He speaks English, Punjabi, Urdu, Guajarati and Swahili. His multilingualism reflects displacements and journeys through India, Pakistan, Tanzania and England. His fluencies also reflect an ability to converse in standardised registers like Punjabi, with specialised inflections like Urdu, and in an east African lingua franca like Swahili, a language derived from Arabic and grown over many centuries incorporating colonial influences of German, Portuguese, English and French.

The combined multilingualisms on Rye Lane reveal the circumstance and ability to converse in more than one language, to read the cultural and economic landscape of a city, and to translate it into products, services and networks. Multilingualism is a ‘citizenship’ capacity of the twenty-first century, constituting a diverse social capital to interpret, to make do, and to renew. In political framings in the UK, citizenship is essentialised as an inheritance rather than a capacity, and the ideological commitment is therefore directed to forms of cohesion and assimilation. While there is broad political and cultural acceptance that universities, corporate boards and trading floors are ‘international’ in their outlook and composition, there is less inclination to engage with how a diversity of origins, languages and outlooks contributes to local life, or as Theresa May puts it, to ‘the personal relationships, the family ties, the social bonds that turn the place where you live into a real community.’

What might the spoken, spatial and economic multilingualisms of the street lend to our sociological imagination? First, is the on-going reframing of questions of belonging in a diverse and disparate world, shifting away from ideological categories or definitions of groupings – be it language, community, ethnicity, nationality – to questions of how groups or associations are renewed and updated through dialogue. While there is an extensive sociology of communication, multilingualism begs for a sociology of fluency: a conscious capacity of an individual or a network to understand and to be understood beyond a single or dominant cultural register. Fluency is therefore not only a practice of communication, but a process that is activated between people and things in order to connect or conduct or mediate exchange, and to foster transition, re-composition and renewal.

Suzanne Hall is based at LSE Cities in the Department of Sociology at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Her current research explores migrant economies and urban space. She is author of City, Street and Citizen (Routledge 2012).