Geof Rayner

The Coronavirus pandemic – the global spread of a tiny non-living protein particle with some RNA inside – has revealed many things, most which we may have already known but which are now brought into sharp focus. I have argued that Covid-19 represents ‘a crisis of ecological public health‘, a collision between the natural world and urbanising, growth-led consumer societies. Months on, with the experience of lockdowns, quarantines, massive economic losses, and now resurgence, an image of life beyond our current ‘Covid-year’ is essential. For many, a safe, effective vaccine is on the horizon and getting closer by the day. But reality is not so simple. A pandemic by its nature mixes chaos with complexity and confusion with disorder. In order to frame these fissiparous circumstances three concepts are considered here – biopower – from the French historian, Michel Foucault, biogovernance, created to address the societal surveillance of biological processes, and biocitizenship which examines human mutual responsibilities.

Covid-19 and its predecessors

By late September 2020, some 213 Countries and territories around the world had confirmed 30 million Covid-19 cases with 1 million deaths. According to the Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center, the regions most affected are Latin America and, in Europe, Belgium and Spain. If Italy gave other European countries a heads-up, the UK’s response was laggard and deficient. UK mortality per population now exceeds Italy, with the USA closely behind. The US death total has now exceeded 200,000, contrasting Chinese official mortality of less than 5,000 (the Daily Express alleged a ‘major cover-up’ suggesting a more likely figure of 40 million deaths.)

Societies forget past pandemics at their peril… and do so anyway. One account of the Black Death suggests it took the lives of up to 60 per cent of Europe’s population, some 50 million people. 75–200 million people may have died across Eurasia and North Africa. The bacterium which caused the pandemic, yersinia pestis, appeared in the mid-14th century revisiting many times. What has been described as a ‘golden age of bacteria’ was driven by increases in population density, growing trade and travel.

The current global pandemic is referenced to the influenza pandemic of 1918. Unlike the Black Death, which killed nine out of ten, and cholera, which took four out of five, the 1918 pandemic was fatal to about 3-4% of those who came down with it. A contemporary account in Science referred to “the complete mystery which surrounded it.” Not just its origination, nor its departure, but basic scientific understanding. It was another half-decade before influenza was understood to be a virus, and another eight decades before a chance finding of a preserved body allowed its genetic code to become available. The British government’s preparation for a future pandemic (Exercise Cygnus), also involved the risk of influenza. In February, the US Institute for Disease Modeling calculated that the new coronavirus was roughly as equally transmissible as 1918, just slightly less clinically severe, but higher in both transmissibility and severity than influenza in the forms it has taken since.

Much remains to be learnt but what is striking is how much is known already. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) first emerged in Hubei province, China, around December 2019, the proximal source of infection discovered as a seafood and animal market in Wuhan. The disease was notified on 31 December and declared a public health emergency of international concern (hence, pandemic) on the 30 January, at which point when there were only 98 cases outside China. The first genome sequence of SARS-CoV-2 was released on 10 January 2020 (on the website, Virological.org) by a scientific consortium led by Zhang. By then it was clear that respiratory and contact transmission were the main routes of spread and early detection and isolation were the key modes of prevention. Currently the UK government plans to commit £571m to the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) Covax programme, split between £71m to secure purchase rights for up to 27m vaccine doses for Britain and £500m in aid funding to help 92 of the world’s poorest countries also access doses.

A recently launched Oxford University project maps the broadening spectrum of world-wide countermeasures, but not defined by effectiveness. Rather they constitute a toolbox of countermeasures, formulated over centuries of practical use. There are around 300 Covid-19 vaccines in development, 40 being currently tested on humans, and 9 of which are in late stage development, known as Phase 3 trials. In April, the UK government launched a Vaccine Taskforce, having already made investments in vaccine development. By September, the US government had invested more than $10bn in some 30 research vaccine projects. Major efforts involve China, Russia, India – the largest producer – the European countries, the WHO and the Gates Foundation and various other global efforts.

From the perspective of international health, the search for Covid-19 vaccines (one single vaccine is thought unlikely) should be part of a long-term global effort against existing, resurgent and novel diseases. It speaks to our different times, perhaps, that one of the largest funders of infectious disease prevention – in the absence of sufficient support from individual governments – is the Microsoft billionaire, Bill Gates. And, while the UN Sustainable Development Goal 3.8 called on the world to “achieve universal health coverage and provide access to safe and effective medicines and vaccines for all”, universal vaccination programmes are now in tatters. In May Donald Trump announcing the US ‘termination’ of its relationship with the World Health Organisation and rebuffed the WHO’s efforts to establish a collective vaccine effort. Along with efforts to pre-purchase vaccines, in effect to ‘corner the market’ for US consumption and thus institute ‘vaccine nationalism’, the prior framework of international health policy, sustained since the formation of the United Nations in 1945 (at US instigation), now seems at the point of breaking up.

Almost by definition, pandemics are low-frequency, high-impact events. They hit hardest when societies are unprepared or where demographic and other factors create vulnerabilities (with Covid-19 these are older age group, pre-existing health, body weight, and environmental exposure risk.) So far, the health impact has been the greater in richer countries and poverty impact in poor countries.

Social Science and pandemics

From a social science perspective, the 1918 pandemic offers thin pickings. Its social documentation was weak, oddly so given an estimated mortality of between 50 to 100 million deaths. That it has almost completely disappeared from collective memory might confirm JS Mill’s remark about how quickly societies recover from disease or war. Such was its immensity, it was suggested in contemporary press comment, that it was impossible for the public to process, especially under the shadow of a devastating world war. (Honigsbaum 2009)

An alternative and certainly bigger starting place might be the experience of all prior epidemics/pandemics and many different types of accounts. In recent years, medical anthropology has contributed powerfully to the understanding of recent epidemics, especially in Africa. It’s a field which addresses the importance of cultural factors and social institutions in enhancing the responsiveness of disease countermeasures and reducing the risks associated with the ‘standardised’ roll-out of biomedical approaches, with their weak footing in culture. Even old narratives may be useful for studying human social reflexes when facing disease threat. One place to start is Samuel Pepys’ unfiltered diary account of the bubonic plague in London in the 1660s, while Daniel Defoe’s (1722) broader geographical account, A Journal of the Plague Year, throws light on the intersection of beliefs and behaviours. Probably the most affecting narrative, Albert Camus’ 1947 book, The Plague (La Peste), is, like Defoe’s work, reconstructed. But It is also experience-derived, being a personal account of a society in social breakdown where the narrative is uprooted and transplanted to an epidemic event occurring a century before (and in French Algeria.) To the historian Tony Judt, Camus’ book was both an allegory of wartime occupation and an observation on ‘plague times’, a situation which exposed human complexity where “dogma, conformity, compliance and cowardice (appear) in all their intersecting public forms.”

In both Defoe and Camus, imagination and reality are blended. In Michel Foucault’s account of the shift from premodern to modern society the French historian attempted to construct a new architecture of understanding. In his lectures at the Collège de France in 1977-78, he presented a novel analytic coinage, biological power (biopower, biopouvoir) alongside the principle of ‘governmentality’. (Foucault 2007) Foucault defined biopower as the “set of mechanisms through which the basic biological features of the human species became the object of a political strategy, of a general strategy of power.” Biopower crosses all biological processes at population level including birth and mortality, health, life expectancy and longevity and conditions that cause these to vary. It also operates at the subjective level through the shaping of knowledge and desire. Biopower is accompanied by ‘biopolitics’, conceived as ‘bioregulation’ by the state. Foucault’s approach, with its apparent dissolution of the boundary between the literary and the non-literary, represents more a progression from earlier accounts rather than a break with them. One enthusiast for Foucault has acknowledged that just as Defoe’s study blurred the line between ‘fact’ and ‘fiction’ his ‘authorial strategy’ achieved much of the same.

Even for those unmoved by Foucault’s approach to history the theme of biopower offers fertile territory. It sets up a new line of questioning about the nature and location of power, through mind as well as bodies. Foucault sees modern modes of power distinct from earlier periods and which gave rise to new forms of surveillance, his oft-cited case example being Jeremy Bentham’s model prison, the ‘Panopticon’. And for Foucault vaccination was located at the opening of a new scientific world of ‘bodies in general’ with biopower expressed through new notions of calculative risk applied to whole populations. He draws out four characteristics of vaccination: the first, that it was “absolutely out of the ordinary in the medical practices of the time”; second, “having almost total certainty of success” (as we see, it was highly challenged), third, “being in principle able to be extended to the whole population without major material or economic difficulties”, and fourth, “being completely foreign to any medical theory.”

It is an approach outside the traditional story of vaccination which begins with a country doctor, Edward Jenner (1749-1823), his small experiment, and then the rush of success in disseminating ideas and biological agents throughout Europe, Russia and the USA, where vaccination became of requirement for army service. In Britain, the 1840 Vaccination Act provided cow pox or vaccinia virus free of charge, followed by a second act, in 1853, which made it mandatory. What is not discussed by Foucault, although he raises the question of ‘resistance’ to biopower, is the campaign by those subject to it.(Durbach 2005) Under pressure from below, compulsory vaccination in the UK was suspended; it continues in the USA – ostensibly the ‘land of the free’, where state laws dictate mandatory vaccinations, such as for children entering school, albeit religious opt-outs apply.

Vaccination was, whatever its benefits, imposed, intrusive, and sometimes ineffective, even harmful, with evidence that it could pass on smallpox (as Foucault’s account acknowledges.) Community opposition was amplified by middle-class opponents from anti-vivisectionists to intellectuals, and most prominently the co-creator of natural selection, Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913). For Wallace, an active socialist, vaccination was an affront to human dignity. It’s been recently charged that Wallace held ‘liberty’ above science, but that’s controversial. For Wallace compulsory vaccination was oppressive and unjustified by statistical evidence.

Today the public debate about the utility and safety of vaccines is framed in terms of ‘vaccine hesitancy’: “the delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccination services.” Such hesitancy was identified by WHO as one of the ‘top ten global health threats’ of 2019. Hesitancy comes in many degrees and forms, from mild anxiety about a medical procedure, understandable when applied to frightened young children, extending to religious or ideologically-sourced and organised denial. Also, as one world-wide documentation of hesitancy has shown, it is often linked to things going wrong in vaccination programmes. Unsurprisingly so.

Louis Pasteur (1822-1895), “father of modern hygiene, public health and much of modern medicine“, was Jenner’s scientific heir who named Jenner’s technique vaccination (vacca, Latin for cow), in his honour. It might be surprising therefore that the French are the most vaccine hesitant in the world. But then this phenomenon is hardly isolated to France as social media has been charged with spreading it. Around one-third of world’s population (2.6 billion) are members of Facebook and other social media platforms, with strong signs of its spreading misinformation.

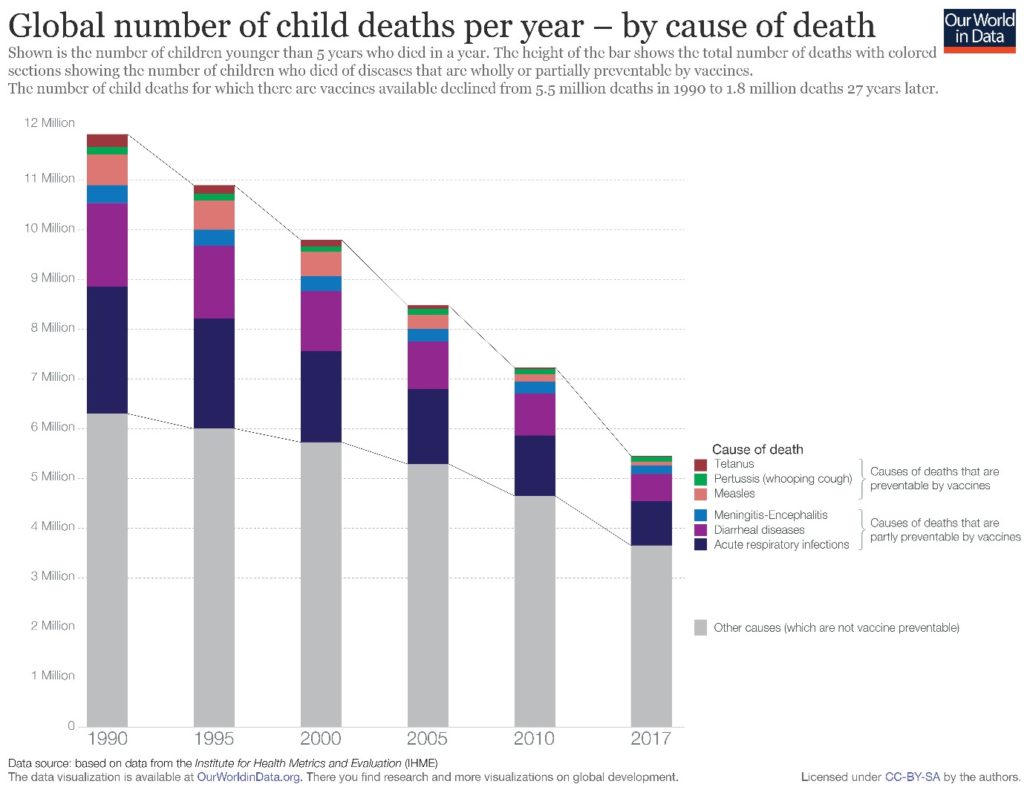

Vaccination is a cheap and effective biomedical intervention which improves as biological knowledge improves. The Swiss mathematician Daniel Bernoulli (1700-1782) estimated that three quarters of people in Europe were infected with smallpox, causing one-tenth of all mortality. Even through the 1950’s there were 45,000 cases a year in the UK and hundreds died. The WHO certified the global eradication of the disease, due to vaccination, in 1980. The measles vaccine was introduced in 1963. Before then the world-wide yearly tally of deaths was around 2.6 million. In places like Cambodia, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) took justified pride in assisting the country eliminate endemic measles and rubella. Today about 86% of the world population are immunised with mortality reduced to an estimated 95,000 deaths in 2017. The wider picture of vaccine success is indicated in the following graph.

Vaccine hesitancy has clouded this picture. Weakening of measles immunisation followed a 1998 Lancet article by gastroenterologist Andrew Wakefield, which, on the basis of a small number of cases linked measles vaccination (by then, MMR), to childhood autism. The article was partially retracted in 2004, but not fully retracted until 2010. It is now considered fraudulent and Wakefield unable to practice medicine in the UK. If other factors played a part, the very success of vaccination in eliminating measles redirected fears away from the measles itself and towards the mechanism of measles prevention. In effect, the explanation supports the ‘risk society’ thesis of the late Ulrich Beck.

Covid-denial, ‘anti-vaxx’ and biopolitical ‘Realpolitik’

Vaccination hesitancy is being reshaped for the Covid age. For some, it has caused their anti-vaccine views to waiver. For others, antivaccination has mingled with conspiracy theory. Over the course of 2020, the brother of the former Labour party leader, Jeremy Corbyn, organised rallies linking conspiracy themes, including coronavirus, vaccination and climate change denial. On 29th August around 38,000 ‘corona-sceptics’ gathered in Berlin, bringing together ‘anti-vaxxers’, ‘hippie moms’ and the far right, according to the Washington Post.

From 20 July in France, the wearing of masks was made compulsory in enclosed public places. One study of the opposition to mask wearing in France has shown a variety of mask opponents, ranging people who argue that masks are useless or self-defeating, to others who express the view that the epidemic is bogus or wearing masks is an act of enslavement. For all viewpoints, the underlying explanatory factor was institutional distrust. French anti-maskers were attracted by libertarian beliefs (rather than simply groups on left or right), and to conspiracy theories. These included government connivance with the pharmaceutical industry to conceal vaccine harm (93% of anti-maskers vs 43% rest of population – an indicator of French vaccine hesitancy). Only 14% of respondents said they had confidence in newspapers and 2% in the information on television. Online media was seen much more sympathetically: 60% of ‘anti-masks’ trust websites and blogs and 51% social networks.

In the USA, ‘anti-mask’ has communal and significatory dimensions, boosted by the connivance, if not the orchestration, of President Trump. The difference with France, Germany and the UK is that these movements strongly associate Covid-19 denial with vaccine hesitancy, whereas in the USA they have separated, at least for those that rigidly follow Trump. The explanation lies in the fact that before Covid-19 Donald Trump was a critic of the measles vaccine and a vocal supporter of Andrew Wakefield. Covid-19 changed all that. The President’s failure to lead society-wide public health countermeasures, and deaths that followed, led to the dimming of his election prospects. Perception of a ‘breakthrough’ vaccine, timed to appear before the election, offered a potential reversal of fortunes. Consistent with his televisual heritage, the programme was titled Warp Speed, from TV series Star Trek.

Disruption of a vaccination programme has occurred before. In 1976 then President Ford rushed out a vaccine for Swine Flu. The medical consequences were severe and it was withdrawn. Opinion polls indicated that such worries about a recurrent episode were spreading. Almost two-thirds of those interviewed (62%) in September thought that a similar situation might occur and that pressure to speed up vaccine approval was compromising safety. Press accounts spoke of disputes within the CDC, with White House appointees directing professional staff to prepare the ground for an early vaccination programme, implying disreguarded safety protocols. The CDC subsequently issued a notice to US states to prepare for a vaccine by November 1st, 2 days before the 2020 election. In response professional staff objected and vaccine manufacturers issued a joint statement confirming that they would undertake no actions which would compromise safety. Trump appointees then resigned and, in late September, the CDC issued new directives tightening procedures and making a pre-election launch unlikely.

Notably, fewer of the President’s supporters voiced concern. But just 21% of US voters say they would accept a vaccine if one became available at no cost, down from 32% in late July. (The British situation too is unclear. The European pharmaceuticals regulator, previously established in London, is now newly arrived in Amsterdam and the situation of UK pharmaceuticals regulation mirrors the wider confusion around Brexit.)

Such disputes constitute an open form of biopolitics. Given Foucault’s ambiguous account of resistance to biopower, it is difficult to know which of these contending forces represents the expression of biopower or its opposite. For Trump’s supporters the answer was clear, government scientists represented the ‘deep state’, but the situation left the rest of public in a state of ambivalence, a situation peculiar for being caused by the government; in effect government-induced vaccine hesitancy.

Do the ambiguities contained in Foucault’s account of biopower point to underlying errors of historical interpretation and flaws in his theoretical analysis? Certainly the case has been made that Foucault’s approach to Victorian history neglected cultural differences between liberal England and Continental Europe, and that he also misunderstood Bentham’s panopticon, in particular that the jailor responsible for surveillance was also himself subject to surveillance. (Goodlad 2003) In any case, state and market institutions have been transformed since the late 1970s. It’s been argued that the new rising regime of power is ‘surveillance capitalism’, with Facebook and other ‘tech’ companies – to use their Wall Street designation – having gained enormous power over the shaping of belief and opinion (Zuboff 2019). And while much of Foucault’s thesis rings true, it hardly helps in understanding changing lines of power, that science too can operate as resistance and that, to use an expression, culture really does matter.

Given these recent biopolitical stirrings, the concept biological governance (or biogovernance) may help. This term applies to the oversight of the production, management, use and regulation of biological materials. One example, and that for which it was coined, has been the use of antibiotics in medicine and animal husbandry, with its attendant cross-over risks to human health and antimicrobial resistance. More recently the governance concept has also been applied to the sharing and storage (biobanking) of human biological materials and related data, particularly as they arise in epidemics and to associated ethical responsibilities. A potential larger field again is the expansion of the concept into biological consequences of human intrusions into natural habitat.

A second concept, biological citizenship (biocitizenship), was first promoted as part of an ethnographic inquiry into the Chernobyl disaster. (Petryna 2002). Synonyms include medical or health citizenship, studies of which have related to genetic risks. What Covid-19 exposes is the larger question of our mutual social-biological interdependence and the obligations we offer to each other. It’s a discussion which began with the German philosopher, Immanuel Kant, assuming a more liberal and distinctively British form in the writings of JS Mill. Certainly, the imposition of rules for public behaviour during the summer lockdown and the degree of communal compliance has become a fundamental issue for disease risk. One social science project has shown that legal imposition alone cannot explain patterns of behaviour, but rather the action of social norms— the way in which people think it is correct to behave and the social pressures this places on them. Placing greater emphasis on mutuality and social norms, produced from ‘below’ rather than ‘above’, might suggest that the Covid-19 experience is not just solely that of biopower, but also engages culture and mechanisms of collective responsibility.

References:

Durbach, N. (2005). Bodily matters: the anti-vaccination movement in England, 1853-1907, Duke University Press.

Foucault, M. (2007). Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1977‐78. Edited by Michel Senellart. London, Palgrave Macmillan.

Goodlad, L. M. E. (2003). Victorian literature and the Victorian state: character and governance in a liberal society. Baltimore, MD, Johns Hopkins University Press.

Honigsbaum, M. (2009). Living with Enza: The Forgotten Story of Britain and the Great Flu Pandemic of 1918. Basingstoke, MacMillan Science.

Petryna, A. (2002). Life exposed: Biological citizens after Chernobyl. Princeton, NJ, Princeton Univ. Press.

Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. New York, Profile.

Geof Rayner is a public health sociologist who has worked in local government environmental services, NHS joint planning, and for the European Commission, WHO and European and national NGOs.