Andréa Gill

In a recent interview following the 2019 launch of his book, Ideias para Adiar o Fim do Mundo (Ideas to Delay the End of the World), indigenous leader Ailton Krenak poses a crucial question to those concerned with growing signs of human and environmental destruction: which end of the world are we talking about? Speaking to centuries of genocidal politics against indigenous peoples across what has come to be known as the Americas, Krenak affirms: “It is not the first time that our end is prophesized, we have witnessed varied prophecies. We have buried all of the prophets.”

Asked, “Has it got worse?” Krenak responds: “No, it has not gotten worse. It would have been worse if we had not been able to appropriate ourselves of the means of communication dominated by white people. So, before we could constitute a narrative, we had to constitute a technology of the whites.” He continues, “Now, we cannot live day to day life pressured by this. In our communities, we have to live the day to day with our lives; and these governments come and go, but they pass, like a flood.”

Here a necessary pause. What narratives are we composing of our inherited histories of the present? How did we get to where we are today, and what (im)possible pathways lie ahead? In what world does “hospitality” become a means to deal with structural and historical relations of oppression and privilege? Here it is necessary to look beyond the hostility/hospitality dyad, which, after all, reflects more a Northern preoccupation and look toward the South.

The rise of authoritarian movements as we have seen in Brazil, congruent with global waves of conservativism, can be understood as a sort of reaction against movements transforming the worlds in which we live. Perceived threats to naturalised places of privilege and power. And, now, with the global experience of COVID-19 so present in our mind/body/spirit, we need to recognise that these movements are not always from or of humans.

As Krenak alerts us, looking to indigenous and oppressed peoples for the secret to survival in a domineering world – and often with the empty and self-centered optimism of the “it gets better” variety – misses the point. We need to become evermore attentive to how we cultivate modes of living and perceiving the world mired in oppressive and repressive sentiments that distract us from grasping what is at stake as a response-ability aligned with the times that we are living in.

For those of us working to dispute dominant narratives, the question remains: how to proceed? Whether up against post-racial or post-feminist tendencies coming from the North, or attacks on what has come to be called gender and communist ideologies by our postcolonial elites in the South, what is in question are perceived threats to the structures sustaining the status quo. Our so-called democracies.

This is not all that new. In the 1950s at a time when the Brazilian social sciences were being institutionalised in the image of an idealised Europe, Guerreiro Ramos and the black movements in our territories were confronting the still-reigning myths of racial democracy and cordiality in Brazil, mobilised as a standard to be projected around the decolonising world by international organisations such as UNESCO. No less violent, its flipside, racism by denegation, as Lélia Gonzalez describes the Brazilian civilizational marker, has configured political oppression and resistance in perverse ways, requiring that it be brought into the conscious realm to be dealt with publicly, openly and directly.

We live in a country where #WeAreAllOne, and its many renditions that circulate widely at times of declared global crises, has proved to generate some of the most authoritarian and aggressive forms of segregation. What needs to be put in place for us to perceive and respond otherwise? How to potentialise the pathways opened/closed at a time when, what was often left unsaid (i.e. in the style of the cordial imaginaries of racial democracy), now has official sanction and dictates public policy and debate?

At an art exhibition launched in the aftermath of the national elections that deepened an authoritarian turn in Brazilian society, a selection of LGBTQ+ artists and a curator from Rio de Janeiro´s peripheries proposed a reimagining of what democracy is. Or more precisely, what democracy does. Eliciting the query: for what democracy? Or as Krenak puts it: “For what be a citizen?”

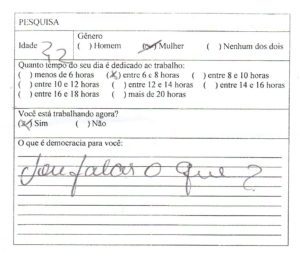

The exhibition project, Bela Verão 2019 – Transcendências (Beautiful Summer 2019 – Transcendences), architected at Galpão Bela Maré in the Favelas of Maré during the months of January and February of 2019, opened a series of dialogues with Brazilian society and contemporary art circuits. On the date that marked thirty years of Brazil´s so-called redemocratisation process, following our last military-corporate dictatorship of 1964, the artist Daniel Santiso and interlocutors went to the streets in the lead up to the much anticipated elections. They set up voting urns to gather responses collected on ballots that registered the question: “What is democracy for you?”

Ballot completed during Daniel Santiso´s performance 13 + 17, Rio de Janeiro, 2018

The urns were met with exhaustion and a hallowing out of the question. With the most pressing pleas made to rights that would be difficult to materialise within the current juridico-normative frames: the right to be respected, to be heard; the right to come and go; and the right to live.

The demand for visibility, recognition and representation are often the basis of claiming rights. Visible to whom, we must ask? Yet there is so little about the right to opacity. To respect life in all of its manifestations, independent of its designated worth to the dominant project of society.

In the heart of the transformed warehouse turned art gallery of Maré, a peripheral territory under military occupation for years in a nominally democratic regime, two large banners, draped overhead, made a radical demand: the right to idleness.

Exhibition in Transcendências at Galpão Bela Maré, Rio de Janeiro, 2019

The right to idleness (direito ao ócio), brought centerstage by the black-and-white banners, invokes a series of reflections on the terms and conditions of citizenship. What does it mean to claim a right to idleness? How does this right inform our ideas about democracy and accompanying narratives of the present? What belongs to the categories of idleness or leisure in their supposed opposition to work, and what is being regulated as a result? What civilisational project is being evoked in the control of the (non)productive?

The answers to these questions are not at all obvious. In sum, they interrogate the use and exchange values embedded in racially and gender hierarchized societies, where enslaved subjects in former colonies and foreign trade companies like Brazil were governed by prohibitions on all that was considered idle. These re/productions of “dangerous classes” bear on much of what today might be classified as art such as samba, capoeira and other practices that opened space for elaborating insurgent living and knowing. The bailes charme during the last dictatorship and bailes funk criminalised today continue to bring together black movements that insist on concretising the possibility of a real democracy.

Beyond its more ostensive moral articulations, what does the currently observed rise of the right have to say to us about our worlds? What is called on to be conserved? If we dare to go beyond making room for difference and otherness – different from whom? Other than whom? Or rather, equal to whom? – how can we become attentive to its multiple reconfigurations and implicate ourselves in its wholesale social transformation?

As we have learned from the force of the myths of cordiality in Brazil, what and whom we (do not) welcome has more to say about the subjects rather than the objects of its discourse, and the world that they seek to re/create. The prevailing idea of democracy – in addition to reproducing a project of society forged by the coloniality of being, power and knowledge – has fueled a disbelief in the very principle of democracy, contributing to its weakening, its depoliticisation. Leaving us with the plea to hospitality as one of the few possible spaces of resistance.

Looking ahead to our next steps, the vital question then remains: how to dialogue with or dispute narratives that propagate, legitimate and applaud the use of violence founded in coloniality? Here processes of re/making memory are central to creating and circulating alternate narratives, renewing the wager on democratic pacts that hold out the possibilities of living together with respect.

Fear generates a life of its own. To not fear the end is to reconceive the beginning and our relationships to the worlds around us. The idea of humanity itself, as Krenak reminds us, is a colonial illusion. Questions open up of who and what we think we are. In turn, an invitation is issued for us to reimagine the contours of democracy, starting with a fundamental recreating of the pacts sustaining our everyday ways of living, knowing and being. And to this end, as the Transcendências exhibition evokes, it is not through processes of (de)valuation that the terms of capitalist, racist and sexist hierarchies of our humanities will be undone. To dare to claim the right to opacity and the right to idleness is to revindicate life in all of its manifestations.

Andréa Gill is a professor and research practitioner at the Institute of International Relations at Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

*All in-text translations are of the author´s responsibility.

Photo credits: http://cargocollective.com/danielsantiso/13-17-Direito-ao-ocio-2018