Simon Parker and Sara de Jong

“Go on look at me. […] What do you see? Maybe I am a refugee […] Maybe I am a story on the news, to turn off and forget.” The girl is looking at you squarely in the eye, walking directly towards you, emerging from a group of refugees fleeing a war zone. This Save the Children advert interrupts your relaxing evening during a commercial break of The Great British Bake Off. The girl’s call to ‘Look at me. Go on, look at me, don’t be shy’ and her piercing eyes, which do not let you avert yours, seeks to disrupt the mostly depersonalised images you watch on the news. Indeed the individualised appeal often feels harder to ignore and therefore could be an effective strategy for Save the Children’s fundraising campaign. But something gets lost in the choice between ‘huddled masses’ and individualised tragic faces, exemplified by the globally circulating image of the refugee toddler Alan Kurdi, who was found dead on the shore near Bodrum in Turkey.

Refugees and migrants are a prominent subject of discussion in media and research, yet it is rare that refugees’ own voices are heard, beyond testimonial snippets of suffering or heroism. Refugees’ own accounts are subjected to scrutiny, checked for errors and inconsistencies in asylum interviews and courts. They get (mis)translated in the language of the receiving country, channelled into legal language or ignored altogether. As relative newcomers, refugees who want to speak up may find it hard to gain entry into political and media arenas or even access basic services. Often the experiences of refugees are re-told by others. And in those stories refugees are frequently presented only as refugees, not as professionals, parents, political subjects, or future citizens. The emphasis either on single cases or anonymous masses conceals the complex experiences of refugees, and the ways ‘their’ and ‘our’ lives are intertwined.

Speaking Up

One of the key questions that emerged from the University of York Migration Network (MigNet) Ideas Salon on Speaking Up, Not Talking Down that we organised for Refugee Week in York this year, and which features in a number of the contributions in this special issue of Discover Society is how can those who are victims of unfair border regimes and bordering practices speak the truth of their experience to power? Linked to this is what role can scholars, researchers and activists play in facilitating the expression not so much of the personal histories of persecution, trauma and mistreatment that many forced migrants have experienced – although this is important – but in disrupting and challenging the othering which inevitably attaches to the terms ‘refugee’, ‘asylum seeker’, and ‘migrant’? And what are the responsibilities of political, academic and media platforms in terms of being inclusive and accountable?

Talking Down

There are many ways in which forced migrants and the undocumented are talked down to, but how is the condescension of the border privileged towards those without a home, a territory or a voice organised and structured? What are its ethical, emotional and aesthetic impacts, not just on those who have been denied citizenship of anywhere, but on those who are fortunate enough to be citizens of somewhere?

The global hierarchies that persist in an age of apparent ‘post’-colonialism continue to reflect the geopolitical disposition of uneven sovereign power that is increasingly displayed in and through state bordering practices. In the territories of the Global North – state constituted elites use their bordering powers to symbolically attack what Adorno (2005) calls ‘nomadic disorder’ through resort to delegitimising terminology such as ‘illegal immigrants’, ‘economic migrants’ and ‘failed asylum seekers’ with the deliberate intention of dehumanising and disempowering the subaltern (Spivak [1998] 2000). This tactic applies equally to the stigmatisation by association technique adopted by immigration, police and border authorities in the frequent reference to ‘trafficked’ and ‘smuggled’ populations where the sovereign gaze finds common cause with the trafficker and the smuggler in viewing the victims of this inhumane trade as cargo or goods that can be traded and inventoried in terms of ‘stocks’ and ‘flows’.

Esme Madill and Rachel Alsop explain in ‘Breaking the Chains: Albanian children and young people seeking asylum in the UK’ how ‘the culture of disbelief’ (Souter, 2011) is such a core feature of the Home Office’s response to accounts of persecution and trauma that a master template of ‘undeservingness’ of humanitarian protection is universally applied to those seeking asylum from certain countries of origin–such as Albania–despite the counter evidence from other government agencies such as the National Referral Mechanism that this nationality is heavily associated with victims of organised criminality, trafficking and forced labour. In this situation it is not enough to be the narrator of one’s own trauma because the regime of truth to which these stories must be told is not prepared to countenance the possibility that its assessment devices and procedures could yield rogue outcomes resulting in someone being returned to harm.

Victor Mujakachi and John Grayson talk about the problematic relationship between providers of assistance to refugees and asylum seekers in Sheffield, one of the first cities in the UK to declare itself a City of Sanctuary, and where a philanthropic approach to refugees is deeply rooted especially among those providing services and meeting spaces from its predominantly Christian faith communities. The authors note that the ‘overwhelmingly white and middle-class’ character of the refugee service provision in the city serves to disempower refugees and migrants while marginalising their voices and capacity for self-organisation. They write

as Mamdani (1973) pointed out, recalling his experience as a British overseas citizen fleeing Uganda, ‘helping’ agencies are creating a disempowered ‘refugee’ identity, giving people a new, dependent role in their new country. As a result, the voices of refugee victims relating stories of suffering become more relevant than testimony from voices demanding rights as potential citizens.

The best way to confront and challenge the pacification of refugee voices, argue Mujakachi and Grayson, is through ‘collective action, research foregrounding the voices and everyday experience of asylum seekers, film making, and demonstrations’ in order to ‘make individual voices loudly heard…not through “stories” but through testimony to change the world for other asylum seekers and refugees’.

Silencing and Screaming

While the media can play a role in amplifying migrant and refugee’ voices, it can also contribute to their silencing, as Ismail Einashe and Daniel Trilling argue, in the interview we conducted with them for Discover Society’s Viewpoint piece. This irony is well expressed in the title of their edited collection, Lost in Media: Migrant Perspectives and the Public Sphere, which we use as a springboard for our conversation. As journalist Daniel Trilling told us, in journalistic, artistic and academic work there is “the danger is that [engaging with migrants’ plight] becomes a shorthand for profundity [where] there’s always a risk that you end up merely aestheticising something and losing whatever else it was you wanted to communicate through that”. Structural global inequalities are reproduced in the hierarchies of the media industry, which means that non-English speaking voices from marginalised actors in the global South and beyond, often only reach the West in a mediated form. Journalists with privileged passports, as Ismael explains, can exploit their mobility by reaching different communities, and use their resources to pay local fixers who facilitate access. The fixers often remain invisible and hardly ever get the recognition for their role in the production of knowledge, while the communities that get ‘represented’ in the Western media often do not even have access to what has been written about them due to linguistic and other obstacles.

Bordering practices also entail an active silencing, as Maurice Stierl argues in his contribution ‘Can Migrants at Sea be Heard?’. ‘Europe has drowned out thousands of migrant voices’ by not intervening when dinghies get swallowed by the sea. And when people in distress have screamed for help, they have too often been ignored. Yet at the same time, humanitarian organisations that are meant to support refugees and migrants are, as Dimos Sarantidis and Simon Parker show, too often complicit in silencing refugees by hiding the violence in detention centres and other locations, once they become contractually interested members of the refugee industry. As Parker notes, the couching of humanitarian protection exclusively in terms of border security not only seeks to achieve discursive closure by forbidding the intrusion of the border oppressed within elite policy making, but the securitisation and illegalisation of forced migration is itself generative of a hugely profitable surveillance and security industry that both sustains and facilitates the EU’s ever strengthening ‘Security Union’.

The deserving and the undeserving

Whether in a drop-in reception centre in Sheffield or in the middle of the Mediterranean sea, our contributors highlight how powerful state and non-state actors engage in sophisticated forms of social sorting around entirely arbitrary and often racist notions of ‘desert’. Marcia Vera Espinoza talks about how even academic researchers can be guilty of over-focusing on categories of refugee that more easily fit our preconceived notions of what a refugee should be, where they should come from, what they should look like, and how they should supplicate. Esme Madill and Rachel Alsop reveal the dangers of being associated with socially stigmatised demographics – young, single, males who might be assumed to have gang associations or any kind of criminal past – are particularly unwelcome anywhere in the world regardless of their humanitarian protection needs. Add negatively ascribed religious and ethnic categories to the intersectional mix and it is not hard to see how the category of the undeserving illegal immigrant is framed in a way that produces a system in which the right of an individual to have their protection claim fairly heard is constantly and aggressively breached.

Even though this is not a requirement of the Refugee Convention, those seeking protection know that having assisted the country to which they are appealing for humanitarian protection (or one of its allies) can help at least to frame their demands in a way which is more likely to elicit public sympathy. If one has not been able to render the right kind of assistance in the right context at the right time, then it helps to have been blessed with exceptional sporting prowess, like the quadruple Olympic champion, the Somali-born athlete Mo Farah, who came to Britain from Mogadishu with his refugee father as an 8-year- old, or Yusra Mardini the Syrian-born Olympic swimmer, now living and training in Germany, who competed in the 2016 Rio de Janeiro games for the Refugee Olympic Athletes Team and who was appointed Goodwill Ambassador for UNHCR the following year. It is not that sporting heroes or popular artists with a refugee background such as Rita Ora or Freddy Mercury should not be celebrated, but rather that the media focus on the successful and the high-achieving underscores the hidden performative script that the ability to live in relative safety without the risk of arbitrary death, imprisonment or harm is not a right but a privilege that non-citizens must earn.

These hierarchies are keenly understood by the border oppressed themselves and even more firmly enforced by the gate-keepers of the giant’s garden. As Salena Godden in The Good Immigrant writes

I now imagine a giant separating people like he is recycling glass at the bottle bank: brown skin glass there, yellow skin glass here, white skin glass over there. […] Arab Oil is Gold Dust. Drowned Brown is Refugee. Immigrant Brown is Better Media Coverage. The giant shrugs. He throws some people in the other bucket and some in the sea to die. His supervisor reminds him that it is vital to tell the difference between Immigrant Brown and Refugee Brown. Let’s be diligent about that. Let’s make sure we pay attention (183-184).

Memory, Loss and the role of the Creative Arts

As Claire Chambers argues in her article, Titanic Refugee Fictions, the remembrance of past human tragedies at sea has its echoes in the contemporary tragedy of the mass drownings in the Mediterranean which the writer Hassan Blasim compares to the catastrophic loss of circa 1,500 lives that followed the sinking of the RMS Titanic in 1912. In just one week in April 2015 two massively overcrowded fishing boats sank off the coast of Libya resulting in the loss of over 1,200 lives, but no Hollywood blockbusters starring the leading screen idols of the day have been made and it is likely any will be made about the April tragedies – although fame of a rather controversial kind was attached to the remains of the vessel that sank on 18 April since it featured as an exhibit in the 2019 Venice Biennale. Jacqueline Maingard’s account of the image-making workshop based on Sine Lambech’s documentary film Becky’s Journey, also helped to foreground the hidden victims of forced migration in a way that empowered Becky ‘through the film to speak her mind, but her agency, if indeed she does have agency, notwithstanding her lively self-reflection, does not and clearly cannot stretch to breaking the cycle of fatal desert journeys’.

How the creative arts can be used to disrupt and challenge the narrative around forced displacement is also the subject of Evangeline Tsao essay where she reflects on the Italian artist Vanessa Vozzo’s use of immersive virtual reality and personal artefacts – including a toy car, or a small jar of oil or perfume — in order to engage viewers more directly with the unknown lives that may or may not have survived the sea journey. ‘I could not help’, Tsao writes, ‘but imagine who their previous owners might be, and what kinds of memory and meaning were attached to them’. Tania Bruguera, who contributes to the Lost in Media collection is an important example of an artist who actively breaks down barriers between the audiences for her work by, for example, requiring visitors to her installation in the Tate Turbine Hall to share their body heat in order to reveal the image of Yousef – a young Syrian refugee who lives in London, and by co-curating other parts of the exhibition with local residents.

This spirit of co-production is also strongly present in Umut Erel and Maggie O’Neill’s participatory action research project with women migrants in London, where theatrical performance and walking methods are used to explore, share and document processes of belonging and place-making. Their collaboration with migrant mothers succeeded in moving beyond stereotypical dichotomies of representing migrant mothers and young girls as only a ‘victim’ or ‘hero’, and showed how these methods can offer ‘ways of engaging with participants’ multiple experiences, subjugated knowledges and constructions of social reality’.

Amplifying Migrants’ Voices

As Sam Hellmuth’s experience of working with newly arrived Syrian refugees in North Yorkshire shows, what professionals, experts and policy-makers think refugee communities need and what they actually want help with in terms of integration or just the practicalities of everyday life can be quite different things. Although the Syrian men and women who took part in the meeting did express an interest in supporting the maintenance of Arabic language in the home, Hellmuth admitted that what she and her colleagues

weren’t quite prepared for was an equivalent strength of feeling in the room about the need for more support for the adults and parents in acquiring English. All the clients were enrolled in regular English language classes, and had fantastic support from local volunteers, but it was apparent that the struggle to acquire English was proving deeply discouraging. For many the lack of practical communicative proficiency in English remained a profound barrier to economic independence, as well as to a sense of safety or belonging in a new place.

Hellmuth’s findings chime with those of the MP Preet Kaur Gill who recognised a similar need among the families from the Syrian vulnerable person resettlement scheme in Birmingham where the lack of ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages) provision was limiting the new arrivals’ ability to ‘communicate properly with healthcare professionals (or) to support their daughter with her complex health needs’. As a recent Refugee Action briefing Safe but Alone found, ‘Government funding in England fell from £203m in 2010 to £90m in 2016 – a real terms cut of 60%.’ The lack of English language provision for migrants and refugees in the 5th richest country in the world is not an accident, but a deliberate policy decision to target the costs of austerity on the weakest and most vulnerable.

While migrants are often viewed as victims, it is often resistance and resilience, as Maurice Stierl, argues, that are fundamental to how far they have managed to reach. The act of leaving one’s country can already be understood as an act of refusal to accept conditions of conflict, poverty, rightlessness and dispossession. In his words, ‘migrant boats can be death-traps but they are also places of political contestation that carry subjects who enact their right to leave, move, survive and arrive’.

Postcolonial and decolonial perspectives recognise the interconnectedness between events ‘over there’ and what happens ‘over here’. They also underline that calls for justice and rights should not be dependent on benevolence but on the recognition of historical and contemporary responsibility for structural inequalities. It is, arguably, not a question of charity but a duty of reparation to offer asylum to displaced people displaced when a state is (co-)responsible for the conflict due to its colonial politics, military intervention, or arms trade. Former military interpreters seeking protection from the states they have worked for, are well aware that ‘they are here, because you were there’ and hence demand rights, not favours.

As the various pieces of this Discover Society Special Issue show, once listening is taken seriously, migrants make their voices heard in various ways. As Sara de Jong argues, ‘recognising migrants as political actors is one important way to work against the representation of migrants as voiceless victims’. Migrants have sought out media channels, legal avenues and political routes, but as Dimos Sarantidis points out, ensuring that refugees and migrants have

the opportunity to participate and speak in conferences, workshops and debates, or encouraging them to individually or collectively contribute to academic journals and blogs will not just amplify their voices but will practically show that they are treated as equal participants in a debate, which mainly involves their own lives.

In the contributions that comprise this special issue and in our public engagement work the editors and contributors have sought to do this, while acknowledging that such voices should not have to rely on our more privileged access to circuits of knowledge and communicative power to find a platform and an audience.

References:

Adorno, T.W. (2005) Minima Moralia. Reflections from Damaged Life, Verso, London.

Godden, S. (2017) in Nikesh Shukla (ed) The good immigrant, Unbound, London.

Mamdani, M. (1973) From Citizen to Refugee: Ugandan Asians Come to Britain, Frances Pinter Publishers, London.

Souter, J. (2011) ‘A Culture of Disbelief or Denial? Critiquing Refugee Status Determination in the United Kingdom’, J Oxford Monitor of Forced Migration Volume 1, Number 1, 48-59.

Spivak, G. ([1988] 2010) Appendix: Can the Subaltern Speak? In Nelson C , Grossberg L (eds.) Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, 271–313. MacMillan, London.

Sara de Jong is Co-Chair of the University of York Migration Network (MigNet) and a Lecturer in the Department of Politics, University of York. She currently researches the claims to protection and rights by former Afghan and Iraqi military interpreters and other Locally Engaged Civilians. Her research focuses on the politics of NGOs, migrant and refugee advocacy and solidarity, and (post-)colonial brokers in migration, conflict and development. Simon Parker is Co-Chair of the University of York Migration Network (MigNet), and Senior Lecturer in Politics at the University of York. He was Principal Investigator of the ESRC-funded project ‘Precarious Trajectories: Understanding the Human Cost of the Migrant Crisis in the Central Mediterranean’ and is currently co-investigator on the ESRC Governance after Brexit project ‘EEA Public Services Research Clinic’ which will be investigating the impact of Brexit on EEA nationals’ access to public services in the UK. Simon’s research and teaching focuses on urban politics, urban political economy and urban theory and on forcibly displaced persons, refugees and migrants. Evangeline Tsao is a Gender Equality Research Fellow at the Centre for Women’s Studies, University of York. Her research interests and expertise include theories of gender and sexuality, intersectionality, participatory visual methodologies and feminist pedagogy. Twitter: @EvangelineTsao

The editors of this Discover Society feature would like to thank Evangeline Tsao (associate editor) for her editorial support and the members of the University of York Migration Network (MigNet) for their contributions.

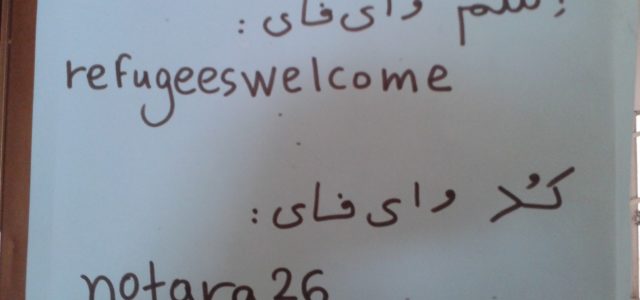

Image Credit: Simon Parker. Refugee children’s art, Notara 26 autonomous space, Athens, November 2015.