Sam Hellmuth

Last year I had the privilege of meeting up with a group of Syrian women and men, newly settled in Yorkshire under the Syrian Resettlement Programme, at a weekly drop-in organised by the Refugee Council. The purpose of our meeting was to talk about language. Working with two academic linguist colleagues, we prepared bilingual handouts in English and Arabic and the session itself proceeded primarily in Arabic. We provided English translation for the volunteers from the local community in the North Yorkshire market town that was host both to our event and to the Syrian families we had come to meet. I had instigated the event thinking that the language we most needed to talk about was Arabic. I wanted to check that Arabic-speaking families newly arrived in the UK knew that it was safe, and indeed best, for them to go on speaking Arabic at home. I had heard anecdotal stories of families being advised to start speaking English at home, to promote the children’s—or even the parents’—acquisition of English. As we shall see, this is bad advice, so we wanted to make sure that families had access to the facts. We called our event ‘Arabic at home’ and we went along prepared to explain the evidence around three key messages.

First, becoming multilingual has cultural and socio-economic advantages, from improved cultural awareness to improved career choices and higher earnings. There is even evidence of improved communication and social functioning in children with autism growing up in a multilingual setting. Second, there is no evidence at all to date that being multilingual has negative effects. Although bilingual children may sometimes display slower development in certain aspects of language, there is no long-term language delay. Indeed, maintenance of the home language promotes proficiency in all languages. In Sweden, for example, all school-age children whose first language is not Swedish are legally entitled to some teaching provision in their mother tongue at least once per week. The quality of this provision varies greatly, but the evidence suggests that even this minimal support for the home language has a positive effect on acquisition of both the home and majority languages. Our third and primary concern—in the light of the stories we had heard about parents being given advice to speak English at home—was to set out the evidence that the choice to give up using the home language can have long-lasting negative effects. The most obvious of these is loss of cultural fluency, severing connections with the community of origin. For example, in a BBC Stories feature, Lola Mosanya talks about the disconnect with her cultural heritage that she feels because she never learned her heritage language. More seriously, the research evidence is clear that lack of early rich linguistic input to children in the heritage language at home can result in a situation where their acquisition of all/any languages is ultimately incomplete. As the following advice for parents of bilingual children from Speech and Language Therapists explains:

“It is important that the home language is not given up in the belief that using English will support the child at school. Children spend more time at home than in school over a year at any age. Children also receive the best language input from people who speak a home language. When speaking a home language, adults are able to provide a very rich language model for children.”

These messages about the importance of Arabic home language maintenance were well received; some families were already reflecting on their family language choices and welcomed an opportunity to talk things through, and we had a long list of requests for more information and advice. What we weren’t quite prepared for was an equivalent strength of feeling in the room about the need for more support for the adults and parents in acquiring English. All the clients were enrolled in regular English language classes, and had fantastic support from local volunteers, but it was apparent that the struggle to acquire English was proving deeply discouraging. For many the lack of practical communicative proficiency in English remained a profound barrier to economic independence, as well as to a sense of safety or belonging in a new place. Based on the findings of a recent round table on second language learning and migration, it is clear that the needs expressed to us in that North Yorkshire community room are far from unique. Why is the bar so high for migrant language learners?

One issue is that migrant language education policies, if they are based on research at all, may be based on evidence from learners who bear little resemblance to the group I met last year. Most research to date on second language acquisition has investigated the type of participants that the academic psychology community now accepts are unrepresentatively WEIRD: Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich and Democratic. Embedded within this trend is a further inherent bias in most prior research towards literate second language learners. Recent work on acquisition of grammar patterns suggests that adult learners without home language literacy show the same basic learning trajectory as literate learners, but tend to make slower overall progress, and are therefore at somewhat greater risk of remaining at an incomplete stage of their language learning. There is a wealth of evidence and resources about the specific language learning needs of non-literate learners, including specific recommendations for the training and professional development of teachers of adult migrants with low literacy, but this advice is not yet in the hands of all those delivering English support.

Anyone who has attempted to learn a language as an adult will recognise the role of motivation in promoting language learning progress, or of lack of motivation in hindering progress, and there is a rich literature on the relative contribution of extrinsic versus intrinsic motivation in language learning success. The emotional force motivating the adult language learners that I met in our community drop-in group was palpable, and almost entirely instrumental in nature, being rooted in the need to negotiate the practicalities of daily life and secure employment, rather than a general integrative motivation to belong. A recent study of highly proficient migrant language learners in Sweden by Alastair Henry suggests that this type of coerced motivation can be effective but places huge demands on the learner’s emotional and cognitive resources. Another source of stress in the language learning process is the linguistic insecurity induced by appeal to a native speaker ideal. Internationally, the English language teaching profession has undergone a shift towards acceptance of English as a Lingua Franca as the goal of language learning, thus prioritising mastery of those features of English which most facilitate effective communication. All adult language learners—and their teachers—should be encouraged and supported to set realistic goals.

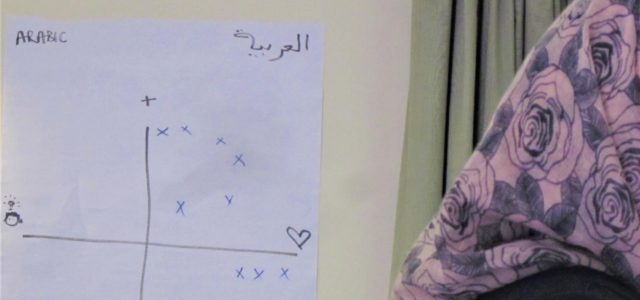

How can we balance the need to acquire a majority language (here, English) with the need to maintain a home language (such as Arabic)? Sabine Little has written about how multilingual families hoping to sustain a heritage language may vary in their reasons for doing so. She proposes a conceptual framework of heritage language identities in which the language is viewed at the intersection of an axis of ‘essential’ versus ‘peripheral’ and another axis of ‘pragmatic’ to ‘emotional’. With our community group we talked about this latter axis in terms of an issue of ‘head’ versus ‘heart’ and if we were to place the probable position of English and Arabic for them, using this framework, it is striking that the two languages would likely fall in entirely different quadrants, with English a language of daily necessity for all, and Arabic as a language of deep emotional well-being for some, but only of cultural convenience for others.

This stark opposition between the majority and home language may well be a symptom of current migrant language education policy in the UK – or at least in England. The only language mentioned in the Integrated Communities Action Plan 2019 is English. There is nothing intrinsically wrong with seeking to ‘boost English language’; indeed, this speaks directly to the strongly felt needs of the families we met with. Nevertheless, it falls into the language policy trap outlined by Dudley Reynolds whereby multilingualism is viewed in terms of an ideology of competition, in which additional languages represent a threat to national identity.

The solution—for language policy and for our response to Syrian families in Yorkshire and beyond —is to take a multilingual turn, and move away from either/or approaches which support one language or the other, to both/and approaches in which the cognitive and socio-emotional resources tied up in a home language can be brought to bear on the task of learning a majority language. A positive role model is provided by the language policy for new refugees in Scotland, articulated in the New Scots refugee integration scheme, which explicitly balances the need to acquire the language of the host community with the emotional, cultural and economic value of the heritage languages that migrants bring with them. Yorkshire has resettled the largest number of Syrian refugees after Scotland, so our ongoing challenge is to find ways and means to better support these families along their path to multilingualism.

Sam Hellmuth is a Senior Lecturer in Linguistics in the Department of Language and Linguistic Science at the University of York whose research focuses on differences across languages (and in particular between different spoken dialects of Arabic) in the expression of meaning through intonation (www.ivar.york.ac.uk). Sam has lived and worked for extended periods in the Middle East and tweets as @samhellmuth.

IMAGE CREDIT: Author’s own