Evangeline Tsao

As millions of people are displaced worldwide as a consequence of wars, climate crisis and famine, over the past few years the forced migration of refugees has become, and continues to be above all a political ‘crisis’. Accompanying the rise of an increasingly state-led anti-immigration ideology there appears to be a lack of understanding of the critical challenges faced by refugees as well as a lack of empathy for those who are suffering. To bear witness to refugees’ experiences, and to raise questions regarding freedom of movement, humanity and global justice, an increasing number of artists—many of whom are also migrants themselves—are engaging with the topic of migration through their art projects. In this article, I reflect upon some of the artworks that focus on representing stories of migration— admittedly, those that particularly touched me—to discuss how their different approaches may evoke emotions and actions, with a hope for a better future.

Curating the ‘The Sea is the Limit’ exhibition at the York Gallery in 2018, Varvara Shavrova emphasised that the artworks are distinct from the sensationalist or even exploitative representations of migration. I am reminded of the photographs portraying masses of refugees being stranded or marched to camps. While these images are supposedly intended to reflect the extensive scale of hardship and dispossession faced by people, they have been frequently misused in news outlets or as propaganda to generate fear – one such example is Jeff Mitchell’s photograph of refugees crossing from Croatia into Slovenia taken in 2015 being used for the notorious Leave.EU “Breaking Point” anti-migration campaign during the 2016 Brexit referendum. Countering this representation of a mass of humanity that can seem unapproachably distant and strange are Nick Ellwood’s Calais Drawings which seek to achieve the opposite effect by ‘re-humanising’ refugees. Ellwood travelled to Calais in 2015, and while he was sketching the refugees, he chatted with his subjects and marked their names, ages and nationalities on many of his drawings. These annotations suggest to me that the refugees are not anonymous sitters but individuals who have personal histories and who are sharing their life stories. What drove the 12-year-old Shahriar away from his home, and where are his family? What kind of meals does Sophie cook at a kitchen in Calais, when resources are so scarce? Amongst these individual portraits there is also a strong sense of community. At the same time, Ellwood’s hastily sketched rough lines mirror the improvised and precarious conditions in which the refugees lived – and in fact the camp was to be evicted by the French government in the following year and its population forcibly dispersed.

Using the medium of film, Ai Weiwei’s documentary Human Flow (2017) weaves in the journeys of millions of people who are displaced in 23 countries. A few minutes into the film, Ai Weiwei situates individual refugees in the centre of the frame, demanding the viewers to ‘take a good look’ at each of them for as long as fifteen seconds. Some refugees stood still, and some appeared to be as awkward as I was, trying not to ‘stare’ while watching a medium that necessarily invokes the human gaze. Following devastating stories and footage of a war-torn city, the powerful representation confronts its audience, seemingly asking: how could you turn your back on their suffering? How do we restore humanity amid ongoing global conflicts and climate crisis? In a controversial gesture of migrant solidarity, Ai Weiwei inserts himself into the film as a thread that connects these different experiences of displacement: giving aid to refugees arriving at the shores, and comforting a woman overcome by her emotions as she talked about the perilous circumstances. In one scene, Ai Weiwei has his hair cut by a refugee in North Macedonia, and in another, he cuts the hair of a man stranded at the US/Mexican border. These representations evoke humanity while engaging with issues of migration, portraying refugees as ordinary human beings who seek a safe and stable life rather than treating them as ‘passing images’. Nevertheless, the film has received some justified critiques, including how its aesthetic risks fetishizing migrants. Additionally, in one particular scene, Ai Weiwei is seen exchanging passports and jokingly talking about swapping residences with an asylum seeker. The moment almost feels cruel, exposing the relatively privileged position Ai Weiwei was in; and in contrast revealing the vulnerability and insecurity of refugees’ living conditions.

Although the film did not offer any political solutions, Ai Weiwei’s work does raise some questions. Alongside the footage of the Calais ‘Jungle’ being demolished is a quote from the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union: ‘the Union is founded on the indivisible, universal values of human dignity, freedom, equality and solidarity’. This, and the deal struck in March 2016 by the EU to return refugees to Turkey in exchange for €6 billion in aid and visa-free travel for Turkish citizens to countries in the Schengen area, calls out the hypocrisy of the EU member states.

In my interpretation, Susan Stockwell’s projects Sail Away (2013) and Trade Winds (2018), installations that depict movements with boats made from paper currency, also allude to the ways freedom of movement is often tied to trade and monetary exchange, as well as other forms of injustice. The currencies arranged to look like boats and seas also mark out some kind of borders; nevertheless, economic exchanges crossing national and geographical boundaries are often taken for granted, making the ‘movements’ of corporations and the powerful much less contested and visible. Freedom of movement for (less powerful) individuals, however, becomes a bargaining chip for political negotiation, such as the case of Brexit, and as a result the high politics of international negotiations shifts the focus from the human scale towards the anonymous mass that tends to remove any sense of common destiny and empathy

The journeys that refugees embark on are full of dangers, and the power of artwork can lie in the ways it generates emotions that bring the audience close to experiencing their perils and dispossession. Vanessa Vozzo’s Apnea Project (2013) is one such example. Vozzo presented photographs and the original artefacts discovered from shipwrecks. These are objects that once ‘belonged’ to someone, and as I looked at the images and the artefacts— including a toy car, or a small jar of oil or perfume—I could not help but imagine who their previous owners might be, and what kinds of memory and meaning were attached to them. At the exhibition there was also a virtual reality device. When I put it on, I was immediately immersed in water, looking at these objects around me gradually sinking to the bottom of the sea, lost in the ocean. Suddenly a white man—perhaps a holidaymaker—appeared, and stared at me for a couple of seconds before he swam away. At that moment, it seemed that I was an object that had been abandoned, hopeless and so distant from any civilization. Not long after, I was starting to feel claustrophobic, because of the sense of helplessness and the fear of being trapped in water. These are the experiences that are rarely seen or felt, and Vozzo’s immersive media artwork, putting its viewers in refugees’ vulnerable position, can evoke emotions that bring the viewers closer to understanding and empathizing refugees’ dangerous journeys.

For some artists, to create representations that aim to evoke emotions is not enough. Tania Bruguera created a series of art installations for an exhibition at Tate Modern in 2018-19. Conceptualized as subtle interventions, one installation demands collective action and another is designed to make its audience ‘cry’. In the Turbine Hall, Bruguera put in a large hidden portrait of Yousef, an asylum seeker from Syria, underneath a heat-sensitive floor. The portraiture would only reveal itself if the audience use their body heat to warm up the floor together. In a room, Bruguera used an organic compound that induces tears, posing the question ‘can we re-learn to feel again?’ The title of the project is an ever-changing number of people who migrated across national borders in the year before, added with the recorded migrant deaths in the duration of the exhibition. Arguably, even the title itself is an intervention, demonstrating the staggering number and casualties of migration. The ideas behind these installations are creative and inspiring, demonstrating how art can be politically involved. Nevertheless, just as I often reflect upon my own research on critical pedagogy and gender equality, I often wonder how feminist and activist work that directly engages with marginalized groups of people can inform structural changes and influence institutional policies? How can research and activist work generate meaningful conversations with people in power, or those who may hold very different opinions? One of the starting points, as Bruguera herself practises and suggests, is to build relationship and solidarity with the communities we intend to represent, and forging wider connections in the society.

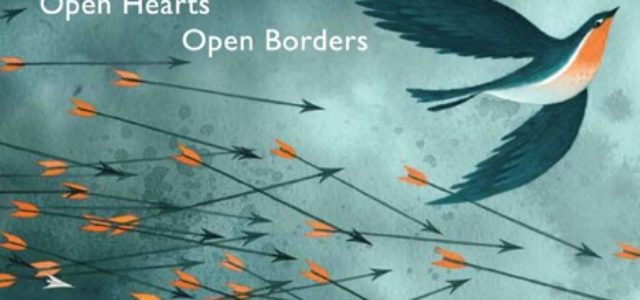

Writing the foreword for the Migrations project (2017), a collection of selected artwork representing migration with illustrations of birds, Shaun Tan emphasizes the importance of using creativity and artwork to craft questions that one may not always know the answers to, and to challenge indifference. The Migrations project invited illustrators from all over the world to draw and send postcards of birds, accompanied with their messages, to the UK; and the risks of damage or loss of the artwork represent the precariousness of migration. In response to the current socio-political climate of borders and walls, many artists decided to emphasize kindness, courage, freedom and hope through their work. The sense of connection and solidarity resonates with the story in Shaun Tan’s graphic novel The Arrival (2006). Without words, Tan depicts a refugee’s experience of migration. Readers would follow his journey, crossing the border to a place where the language, social system, produce and animals all seem a little familiar yet totally strange – reminding me of my own experience when I first moved to the UK. In such a strange place, smiles, companionship and stories are part of our humanity that can be shared across linguistic differences. Perhaps with more kindness and a will to understand, we would be able to rebuild a global community that is more sustainable and hopeful for the future.

Evangeline Tsao is a Gender Equality Research Fellow at the Centre for Women’s Studies, University of York. Her research interests and expertise include theories of gender and sexuality, intersectionality, participatory visual methodologies and feminist pedagogy.

IMAGE CREDIT: Copyright Richard Johnson. Cover illustration Migrations (2019) edited by The International Centre for the Picture Book in Society at University of Worcester, published by Otter-Barry Books.