Navtej Purewal

The results of the 2019 Australian and Indian general elections, announced within days of one another on May 18th and 23rd respectively, were each in their own way a vote for crony capitalism and ‘development’ over environmental, sustainability and social justice concerns. The victory of the BJP in India and the Conservative Party in Australia lay bare how global capital is increasing its influence within and across national political contexts in shaping political narratives and outcomes. By reinforcing old and drawing new lines of influence through adapting regimes of governance, this era of crony capitalism highlights the ‘unexceptional ‘nature of neoliberalism (Cross, 2010) in its manifestation across India and Australia. Mining sites and ‘special economic zones,’ which are formalising features of extractive capital’s pursuit of natural resources normalise dispossession in a time when the idea of ‘development’ wins votes.

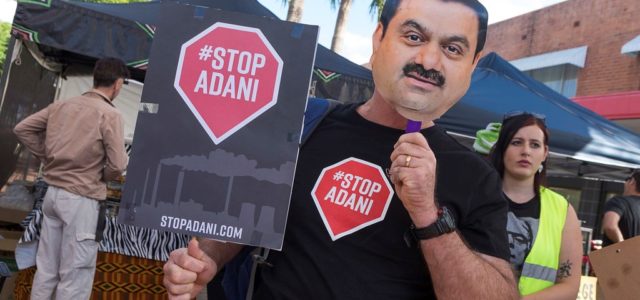

One corporation in particular, the Adani Group, draws a direct link between Australia and India in terms of the forces that led to these electoral outcomes. The Ahmedabad-based Indian conglomerate the Adani Group, with an estimated $12 billion-dollar revenue and $28 billion dollar assets holding and a diverse business profile is most widely known as India’s largest private power producer and port and terminal developer. The consolidation of transport and shipping logistics, access to mining sites, and privy access to government approvals has seen the company expand its portfolio culminating in plans for its largest project to date, the excavation of the Galilee Basin for the Carmichael Adani mine project in Australia.

‘Bad capital’ and ‘good capital’: Stop/Start Adani in Australia

The BJP’s narrative of India as a rising global economic power has relied upon such corporations as the Adani Group. Adani’s pursuit of the Carmichael mining site in Australia shows its understanding of how to navigate the political terrain of another neoliberal context. Australia, like the US, Canada and South Africa, was constructed out of settler colonialism, primitive accumulation and dispossession through violent acquisition of land and the biopolitical replacement of indigenous populations (Grewcock, 2018). The violent settlement was further forged by restrictions, with backing from trade unions, placed on Asian labour migration from reaching the sugar plantations and gold and coal mines since the 1850s. This was extended into a seven decade White Australia immigration policy from 1901 to 1973 aimed to block Asian migration altogether.

Increasing levels of Chinese government and corporate investment in Australia has run parallel to the xenophobic political discourse around Asian immigration and settlement in Australia. Openness to Asian capital investment alongside normalised hostility to Asian migration have been an ongoing feature of mainstream media and political discourse on Australia’s relationship with Asia. In the 2019 Queensland state vote, this bifurcation was starkly demarcated between ‘good capital’ and ‘bad capital’ – economic capital (i.e. infrastructural capital investment) and human capital (i.e. racialised labour), respectively. Decades of anti-Asian immigration played up by political parties in their portrayal of ‘bad capital’ became diffused into the Adani coal mine project’s narrative of ‘good capital’. While Queensland has historically been one of the most prone states to racist political rhetoric, its vote for ‘good’ Indian capital (the Start Adani platform) led to the result which saw the result tip in the Conservative Party’s favour.

Australia’s Stop Adani Campaign and associated climate emergency global protests were overridden by a provincial vote in Queensland in favour of the Carmichael coal mine and rail project project giving a mandate to ‘Start Adani’ through the issuing of state-level environmental management approvals. The Start/Stop Adani debate was, in effect, a referendum that shaped the outcome of the 2019 Australian general election.

As environmental activists and the Stop Adani campaign have vociferously highlighted since the project’s initial approval in 2014, the excavation of the Galilee Basin and plans for shipping coal from the basin each year (mainly to India) threaten the Great Barrier Reef, one of the Seven Wonders of the World, which is already under threat from the forces of climate change. In an era of divestment from fossil fuels and increasing interest in renewable energy, Australia’s approval of the Adani coal project, even in its curtailed current proposal, stands in bold defiance and denial of the climate emergency.

As the approvals were announced within one month of the Australian election, the Adani mine is set to be one of the world’s largest mines. It is not a coincidence that it lies in Australia’s most conservative state with a long history of land-theft, favoring industry over aboriginal rights, and dependence on primary industry, in particular mining and agriculture. The environmental lobby struggles to rally locally against coal in Queensland.

‘Development’ by dispossession

The Adani project is a prime example of accumulation by dispossession which encapsulates neoliberal policies seeking to privatise and dispossess the public of land and resources, even when there is an appearance of state redistribution. In Australian Adani country (Queensland), voters, who are regularly mobilised around anti-immigration (“bad capital”), were motivated by the idea of ‘development’, that the planned Carmichael coal mine would bring jobs to the region against the Labor Party’s environmental policy and opposition to the Adani mine project. Meanwhile, the regionally protectionist and minor conservative/right-wing parties contributed to the sidelining of the Labor Party’s ambiguous stance on Adani, encouraging Queensland voters to reject the concerns raised by the Stop Adani campaign.

A longer term view understands the Adani mining proposition as a continuity in Australia, a place created out of dispossession wherein the “settlement” of Queensland occurred through violent predatory accumulation of land through the European colonial settler state. Non-indigenous Queensland voters were voting for dispossession from land already stolen.

The Adani Group is experienced in accumulation by dispossession and has played a notorious role within India’s burgeoning system of crony capitalism. Gautam Adani’s rise synchronistically parallels Narendra Modi’s ascent in the Indian state of Gujarat since 2002. Both of their successes can be attributed to the “Gujarat model“, hinged on crony capitalism: capital-intensive infrastructural development, incentives and tax subsidies to corporate investors, and loans provided for such projects by state banks.

All of this occurred alongside declining public expenditure on education, health, environment, formal employment, and, most significantly, the overt use of Hindutva ideology to promote majoritarianism, governance and economic globalization. Adani is not the only oligarch within the ascent of Indian global capital. The split Ambani (Reliance) empire has a scandalous track record in India, in particular over its ambitions to capture the Krishna Godavari (KG) Basin which is spread across 50,000 sq km near the coast of Andhra Pradesh in the Bay of Bengal. Despite Article 297 of the Indian constitution which states that a production sharing contract would maintain that the natural resource remains publicly owned, Reliance has operated as a parallel state in India by monopolising control over financial, human and environmental resources.

It is important to recognize the far-right forces supporting the Gujarat model which have enabled crony capitalism in India. The Gujarat model emerged out of the spectre of the 2002 anti-Muslim pogroms where state impunity and complicity were found at every level from the attackers, police, courts, judges, to the office of the then Chief Minister who is now India’s Prime Minister for a second term. The 2019 Indian election just one week after the Australian ballot saw Narendra Modi’s BJP gain sizeable numbers of seats, successfully banking on the above-mentioned reputation of state-endorsement of attacks against a minority community. The Indian election, like the Queensland result, showed how big business and the neoliberal state maligned protests about the state’s human rights record by turning it into a referendum for ‘development’.

The maligning of social justice concerns in a bid to show a pro-business/’development’ stance is evident in how Adani’s home state model has become the national model in India. Only one year after the 2002 Gujarat pogroms, Narendra Modi as Chief Minister of Gujarat declared that the Vibrant Gujarat summit would take place annually to attract investors. The synergies across the religious right, movements for social conservatism, and neoliberal globalisation are embedded in India’s ruling BJP party.

As the Adani coal project goes ahead in Queensland, the prospect of jobs and ‘development’, which was the core of the Start Adani message, is a plagued election outcome when the Adani track record is examined more closely. There are countless cases and examples of exploitation [https://adanifiles.com.au] of workers within Adani projects in India. A lack of attention to health and safety has resulted in deaths at work sites and power plants, and non-compliance with labour laws by outsourcing to contractors has seen the employment of child and underpaid workers.

The projection and promises of ‘development’ created ripe conditions for crony capitalism to thrive and win over environmental, social justice, and ethical concerns in attracting voters in both of these contexts. However distant they may seem, Queensland in Australia and post-2002 India have shown how electoral support for neoliberal, unchecked corporate ‘development’ can be rallied from platforms actually calling for accumulation by dispossession.

References:

Cross, Jamie (2010) “Neoliberalism as Unexceptional: Economic zones and the everyday precariousness of working life in South India.” Critique of Anthropology. 30(4), 355-373.

Grewcock, Michael (2018) “Settler-colonial violence, primitive accumulation and Australia’s Genocide.” State Crime Journal. Autumn 2018. pp. 222-250.

Navtej Purewal is Visiting Chair in Contemporary India In the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Sydney and Professor in Political Sociology and Development Studies at SOAS, University of London.