Elisa Pieri

The threat of new global pandemics has become a pressing concern in the West. The likelihood and impact of future pandemics are discussed amongst scientists working in various medical fields – from immunology to virology, epidemiology and veterinary research. Pandemic risk and the planning towards its mitigation feature increasingly in policy discourse and strategy at various levels. Most nations have drafted plans to mitigate pandemic risk and are part of global networks for infectious disease surveillance and response.

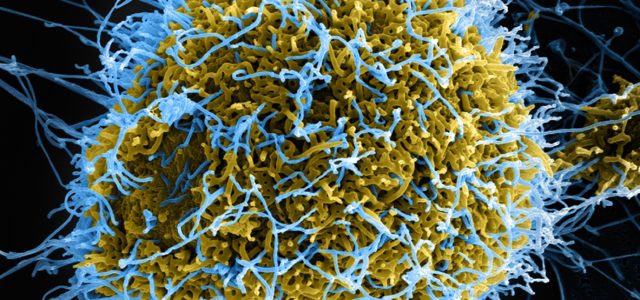

This level of preparedness is not matched by a widespread public awareness of the issues. The sparse information diffused in the public domain tends to only appear in times of crisis – for instance during the 2014-15 West Africa Ebola outbreak, and even then only with a considerable time lag. Moreover, it often envisages the threat as coming from outside (i.e. outside the Global North). How the threat as currently conceptualised fosters little debate on best measures to implement, and very little reflection on some of the likely and varied causes of a forthcoming pandemic.

Practitioners recognise the need to embrace a one-health approach, one in which people’s health is intrinsically linked to that of animals and to the ecosystem, and in which animal and human health professionals work much more closely together, and collaborate with environmental scientists too. This is vital considering the effects of changes in climate (for example warmer temperature extending the habitats of mosquitos that are vectors of a range of diseases) and key to our ability to better mitigate against the risk of zoonoses, or diseases that are jumping species barriers.

Currently, the flawed way of conceptualising infection as coming from the outside detracts from our ability to develop effective responses. On the one hand, it invites a fortress mentality, which results in ineffective actions being taken, as best illustrated by the recent deployment of UK airport and ports of entry screening during the latest stages of the Ebola crisis. On the other, important outbreak triggers, including our established practices of intensive food production and intensive animal farming, are hardly publically debated in relation to pandemic threat and even less likely to be scrutinised in the public domain. Incidentally, what gets highlighted instead is a set of farming practices (such as backyard animal rearing for own consumption), or food provisioning (such as hunting for bush meat, as was apparent during the Ebola crisis in Sierra Leone), prevalent in other parts of the world.

The likelihood of future outbreaks is something upon which experts now agree. Yet, the scientific community did not always regard lethal infectious disease to be such a significant threat. In the post-war period, optimism prevailed and in the 1960s and 1970s the scientific consensus had consigned infectious disease to the history books. This was due to the development of anti-viral medication, and the promise of new vaccines and antibiotics research. Then with the advent of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the early 1980s, and the isolation of Ebola and other haemorrhagic fevers in the mid to late 1970s, it became obvious that novel and lethal infectious diseases were still emerging. Diseases already known to us were also suddenly re-emerging in variants that were both more virulent and proving resistant to known antibiotic treatment.

The advent of SARS, the coronavirus that caused a global outbreak in 2002-2003, was a watershed in terms of professional and—albeit briefly and to a lesser extent—in terms of public understanding of pandemic risk in the West. A disease outbreak could now travel fast and, in a matter of hours, spread to some of the most densely populated cities globally, thanks to the intense and extensive mobility of citizens around the globe. SARS was rapidly brought under control, despite causing approximately 900 deaths globally, since its mode of transmission meant it could be arrested though stringent traditional methods of viral infection isolation and quarantine. However, as those involved in flu pandemic preparedness continue to highlight, in the likely event of a future type A influenza pandemic (not unlike the Spanish Flu which occurred at the beginning of the 20th Century) quarantine would be ineffective, and apocalyptic death tolls may ensue, resulting in the death of tens of millions of citizens globally.

The UK National Risk Register (NRR) regards the spread of emerging infectious diseases, and specifically pandemic influenza, as a tier one risk, the most serious category of risk envisaged by the register. This mirrors the international alarm and efforts at European and global level to ramp up a rapid coordinated response to any future major global infection. Following the WHO-led reforms to the International Health Regulations in 2005 and the creation of new dedicated instruments for international surveillance and reporting of infectious disease, such as the launch of the WHO’s Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN) in 2000, and the EU European Centre of Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) in 2005, more than 100 countries have drafted formal plans to respond to a possible pandemic event. Guidelines are produced and widely circulated by institutional actors at various levels of governance, national to international, including by the non-governmental actors that routinely respond to such crises, such as Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and the Red Cross.

An impressively heterogeneous set of practitioners and responders (from NHS front-line services to the military) and policy makers are drafting these plans and guidelines. Yet no input is being sought from citizens. No input on the desirability of such measures. Both medical and logistic solutions are intrinsically connected to cultural values (e.g. acceptable burial practices) and priorities (e.g. which groups to prioritise under crisis conditions when resources will be scarce – for example children, senior citizens, the vulnerable, first responders and so on). No input as to the likely or previous effects of these very measures, when these have already been deployed and experienced, such as quarantine and isolation, or triaging access to ventilators and other limited medical resources (as was the case in Toronto hospitals during the SARS outbreak). No participation in setting priorities, even if issues of allocation of scares resource are expected to arise.

An outbreak is expected to occur imminently. Yet great uncertainty remains, as to what pathogens may trigger the infectious outbreak and thus on a whole series of related key factors – including the pathogen’s origin, its pathways for transmissibility, infectiousness, fatality rate, responsiveness to known treatment (or indeed to any newly-developed vaccines, in due course), and its capacity to rapidly transform further. Under these conditions of radical uncertainty it is even more important to be procedurally fair, to be inclusive of all stakeholders in the decision-making process and the preparedness activities. Yet, this is certainly not the case currently, with publics being excluded from any planning input and preparedness exercise, and with the lack of any public debate on pandemic risk.

Involving publics in open debate on pandemic threat and preparedness would result in a process that is procedurally fairer and, quite possibly, in solutions that may achieve better uptake rates under an emergency. More importantly, ensuring all stakeholders participate in co-shaping the preparedness strategy and planning will hopefully also generate better mitigation solutions against the next pandemic.

An open, inclusive and sustained public debate might also prompt reflection on other aspects of pandemic risk – for example the very causes of pandemic outbreaks. If we consider the case of pandemic influenza, the threat comes from a new strain that may combine high lethality and ease of human-to-human communicability. Its origin may be connected to natural biological processes of viral (antigenic) drift and shift. These are the slow genetic change and the sudden unpredictable and major re-assortment of genetic material. The outbreak may be facilitated by natural animal behaviours, such as migration patterns, and assembling of waterfowl in certain natural reservoirs. Animals may spread the disease as carriers or transport it in forms that are lethal to them too.

While pandemic outbreaks may have different origins and may well be triggered by natural processes that cannot be stopped, nor managed (such as migration patterns), they are also likely to result from risks generated by a range of human activities and economic practices. These range from deforestation to intensive animal rearing, very rapid urbanisation and inadequate sanitation, inadequate animal husbandry and housing, including misuse of medication in animal rearing. We appear to be less prepared to intervene at the policy level in these areas. For example, the EU has banned antibiotics for growth promotion in animal farming since 2006, but many other countries, including in the Global North, have not followed suit, which increases risk of antimicrobial resistance to pathogens. When the focus is publicly drawn to risky farming and food practices, too often it highlights activities depicted as pre-modern and exotic, such as using wet markets in Asia (where poultry are purchased live and slaughtered ahead of home cooking and fresh consumption), or backyard rearing of chickens in Thailand. Little, if any, public reflection is directed at intensive farming, or at how our reliance on certain food products sustains the spread of monoculture, deforestation and encroachment on animal habitats and environments previously removed from human activity, bringing species in close proximity, and facilitating the risk of zoonoses. Publicly debating the links between human health, animal health and the environment in the context of pandemic risk may perhaps encourage policy makers to think through the issues in a more integrated and inter-connected fashion – as practitioners already seek to do.

Elisa Pieri is a Lecturer in Sociology at University of Manchester. Her work focuses on security, the urban, science and technology, and governance of radical uncertainty. She conducts research on Securing Cities against Global Pandemics (Simon Fellowship Award, 2016-2019). Her previous interdisciplinary research projects were on emergent technologies, including genomics, biometrics and identity technologies.

IMAGE CREDIT: “Ebola Virus” by theglobalpanorama licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0