Yvette Taylor

“Estrangement feels very taboo…it’s almost like having to out yourself a lot of the time to people…” (interviewee)

Widening participation (WP) agendas are supposedly a key priority of UK universities, supporting the transition and inclusion of under-represented groups. In the UK, the WP agenda has a large portfolio of target groups, including low-income students, people with disabilities and care leavers. Often these cohorts are viewed in silos, as discretely ‘international’, or ‘non-traditional’, for example, and policies are often replete with euphemisms, which don’t name the particular intersectional inequalities impacting on access and the ‘student experience’. What then of ‘estranged students’ whose experiences may not fit or may even be ‘taboo’?

The status of student estrangement – of those who have unstable, minimal or no contact with immediate family – has been added to the widening participation mission. The status of ‘estrangement’ was first introduced into student funding in 1997 in England. In Scotland the same status was only recognised in 2016, representing a gap of almost 20 years. Strides are being made particularly through initiatives guided by organisations such as Stand Alone, which acts in four key areas of support, policy, research and awareness-raising. Yet higher educational institutions can still be regarded as failing WP priorities and as contributing to estranging experiences of ‘widening participations’ students.

Stand Alone found that 41% of estranged students contemplate dropping out of their studies early (Stand Alone, 2015). Recently, Stand Alone queried the Student Loan’s Company’s decision to select – or spy on – 150 estranged students, asking them to provide evidence that they were no longer in contact with their families. Proving a negative, or an absence, is of course rather difficult and much upset was caused by the threat that failure to respond within 28 days with the required proof would mean suspension of funding and, thus, studies. Worryingly, social media accounts were monitored to find out if ‘family contact’ had been made, where, for example, random Facebook posts were collapsed into evidence of contact and support.

Much research has shown that supporting access to university is only one of many critical ways to effectively and successfully support academic trajectories. The Student Loan Company’s actions highlight the fact that once students get into university they can continue to face barriers and be disadvantaged by expectations, norms and policies on family structure, connectedness and finance as often assumed as in-place, continuous and uncontroversial. Our research, funded by the Carnegie Trust and the Society for Research in Higher Education, hopes to extend existing research in HE transitions (Purcell et al, 2010; Furlong and Cartmel, 2005), including Precarious Pathways (Purcell et al. 2014-17) and the Paired Peers project.

Estranged students, who have unstable or minimal contact with their parents or wider family, may lack the vital ‘safety net’ of other students, receiving little to no financial or emotional support while studying. As a result, estranged students may face many challenges, including securing stable accommodation outside of term time (or feeling isolated in university accommodation when other students have left to go home). The emotional burden of feeling outside the typical ‘student experience’ can result in mental health issues related to stress and isolation, as reported by Stand Alone. The lack of familial face-to-face proximity may mirror the experiences of international students but not enough is known here, or about the differences among ‘estranged students’.

Initial findings from our investigation into the experiences of estranged students in Scottish universities highlights the inter-related issues of accommodation (availability and price), personal finances and lack of support networks. When it comes to accommodation estranged students find themselves in a very strange place.

On the one hand, they have the prestigious status of being HE students, yet, on the other hand, they are always at risk of not having a place to live. These two realities don’t often go together in people’s imagination:

“Because most people actually live at home. … a lot of the support … there’s still a lot of antiquated ideas of ah, ideas that are not relevant to, to me, which is to say ah over the summer ah why not just ah, you know, go and stay with your parents?” (interviewee)

Estranged students who live in halls of residence can rarely afford the high rent costs and often take on near full-time employment to make ends meet, and sometimes face eviction during the summer period. These constitutes a huge problem for students who do not have a family home to return to, and are essentially homeless and reliant on sofa surfing while many classmates go home to their families:

“So when I came to the end of first year we had a wee situation where I was, I was living in halls and, and the university were saying ‘well you need to vacate the halls on this date’, and I said ‘well I don’t have anywhere else to go and I don’t have a job, and my student loan’s ending’ [...]and as a result I actually remember I moved all my stuff out of the halls onto the grass outside the, the building […]and for that whole summer I ended up being homeless […] I felt that at that point the support structures were not assisting people that were in my shoes basically.” (interviewee)

When it comes to accommodation HEIs seem to take a one-fits-all approach, again overlooking the needs of students who fall outside a traditional understanding of student and family life. Some interviewees, while pleased that their institutions were signatories to the Stand Alone pledge, committing resources and actions to supporting estranged students, felt sceptical about the reach of these resources. Others didn’t know they existed or felt unwilling to come forward and claim support given the ‘taboo’ of estrangement: likely no-one easily identifies as ‘non-traditional’ or estranged:

“I don’t really like to title myself estranged that much… it’s Stigmatising (…) like no matter what bad things happen to me, you know, it’s like a very bad beginning, bad upbringing, or everything, a lot of bad luck, but I’m coming through it”. (interviewee)

It is important to consider student’s own definitions, as well as resistances and personal strength evident in all discussions of the challenges faced by estranged students. Often these students face isolation, uncertainty, financial instability and fear of homelessness, and yet have still secured a place at university using whatever limited resources, personal and practical, to navigate barriers to their academic success.

In order to highlight the experiences of estranged students to a broader audience our research team held a one-day conference on 20th of September at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow. The aim was to consider the role of higher education in meeting the needs of estranged students, and also to give estranged students a voice. In doing so we hoped to shine a light on issues that mark and differentiate their academic journey from that of other students in particular, issues of social and economic capital and precarity.

The research team at Strathclyde invited CEO of Stand Alone, Becca Bland, Dr Lucy Blake a researcher in family estrangement, as well as widening participation teams in higher education, and also presented initial findings from our qualitative research. The event aimed to open dialogue about estrangement in higher education, and how to make the experiences of estranged students less ‘taboo’ by promoting awareness and sharing ideas of best-practice. Attendees were encouraged to share ideas with each other and online using the hashtag #StrathEstrangement, aiming, with Stand Alone, to give estranged students ‘a voice and a face’.

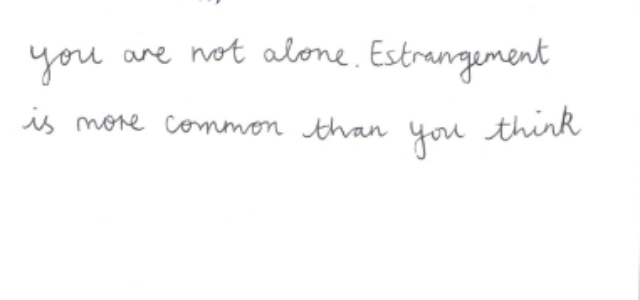

In our research we wanted to help promote the voices of estranged students, and share their experiences in their own words. We ask estranged students participating in our research to write down one ‘take home message’ on a postcard. Messages could be addressed either to other estranged students, the university, or the widening participation team. Most messages showed support and encouragement for other estranged students, one reading simply, “Keep on going. Don’t give up”, and another “It will be okay. Just hang on in there” (see below).

Reference:

Furlong, A. and Cartmel, F. (2005) Graduates from Disadvantaged Families: Early Labour Market Experiences. Policy Press: Bristol, UK. ISBN 9781861347800

Yvette Taylor is Professor of Education in the School of Education, University of Strathclyde.