Chris Linder

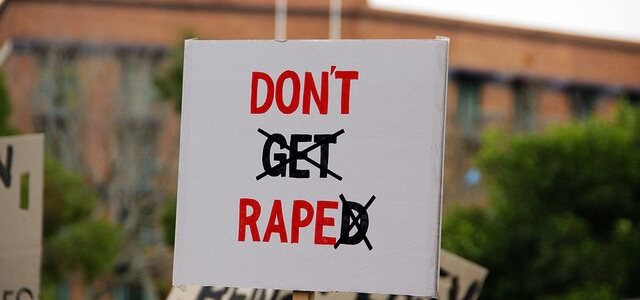

As we ramp up to begin another academic year, college and university administrators and educators are also ramping up their efforts to educate students about campus sexual violence. Unfortunately, in many cases, this means that we’re hearing a lot about the ways that potential victims can reduce their risk of being sexually assaulted. Although it is certainly important to remind people of some of the ways they can take care of themselves, the reality is that for campus sexual violence, many of the “safety tips” we offer students are misleading, confusing, victim-blaming, and ineffective.

For example, the most common “safety tips” I have observed on the campuses I have worked over the past several years consist of the following:

- Be aware of your surroundings; never walk alone; use the “buddy system.”

- Reduce your alcohol consumption.

- If you see someone “taking advantage” of another person, call the police or find another way to intervene.

Although well-intended, each of these “safety tips” stops short of actually addressing the root of sexual violence: power.

The first tip to be aware of one’s surroundings is a generally good suggestion as it is important for people to be mindful of their environments; however, as it relates to campus sexual violence, it may actually be harmful. The vast majority of sexual assaults involving college students (upwards of 90%) happen between two people who know each other; perpetrators target people they know and with whom they have a relationship. As a former victim advocate on a college campus, I heard several stories from survivors who were assaulted by the very person they thought they were safe with – the “friend” they asked to walk them home so that they did not have to walk alone.

Certainly, I am not advocating that we stop telling college students to be mindful of their surroundings; however, we must go further – we must teach college students about the actual realities of sexual violence on our campuses. We must make them aware that perpetrators often target people they know and that even though they don’t want to believe it, they are far more likely to be assaulted by someone they know than by a stranger jumping out of the bushes.

Next, many campus education programs focus on telling people to reduce their alcohol intake, which is not inherently a bad message; however, when used as a strategy for reducing sexual violence, it is confusing and victim-blaming. Educators hear the statistic that alcohol is “involved” the majority of campus sexual assaults and they automatically think that they can reduce victims’ risk of assault by telling them not to drink. However, when one digs a little deeper into the research about alcohol and sexual violence, the research actually indicates that perpetrators use alcohol as a weapon and excuse to commit sexual assault. Some perpetrators intentionally use alcohol to get their target drunk to reduce their inhibitions so that they can “take advantage of them.” In these cases, it is important to teach college students to pay attention to patterns of perpetrators – to note when someone is insisting that they drink and continually feeding them alcohol.

Additionally, research indicates that alcohol actually exacerbates perpetrators’ likelihood of committing sexual assault – men (98% of perpetrators are men) who already participate in sexist, entitled behavior related to sexual behavior become even more aggressive when they consume alcohol. So again, teaching college students about the risks of over-consuming alcohol is not inherently bad – the problem is that we’re not teaching correct information about the relationship between alcohol and sexual assault. The message must be more complex than “don’t drink and you won’t get raped” because THAT IS NOT TRUE! Plenty of survivors were completely sober when an ill-intended perpetrator raped them. Instead, we must teach students about the ways perpetrators use alcohol as a weapon and excuse for their behavior so that college students can be more informed about the actual dynamics of sexual violence.

Finally, many campuses have moved toward incorporating bystander intervention programs as a part of the sexual violence education and prevention programming. While bystander intervention programs have begun to shift the focus to perpetrators of sexual violence, rather than solely teaching potential victims how not to be assaulted, these programs still stop short of actually intervening with perpetrators. Further, many bystander intervention programs conflate alcohol and sexual violence when teaching students bystander intervention skills, which again, distorts the problem to being about alcohol, rather than about a person with the intent to cause harm or disregard another person’s boundaries.

Perhaps most harmful, bystander intervention programs may exacerbate myths and stereotypes about perpetrators and victims of sexual violence. In one study, white women indicated they would be less likely to intervene in a potential sexual assault situation if the potential victim was Black. Similarly, given the racist history of sexual violence, it is likely that people would be more likely to intervene if a supposed perpetrator was a man of color or a “creepy” guy (aka “stranger”) than if they were a “good,” white middle-class, college man. Again, although it is important to teach college students some potential signs and patterns of sexual assault, relying on bystander intervention as our primary prevention strategy without teaching students about the intersections of racism and other forms of oppression with our perceptions of who is a legitimate survivor or perpetrator of sexual violence actually causes further harm to already marginalized students on our campuses, and doesn’t actually reduce sexual assault.

So what? What do we do?

We must focus on power as the root of sexual violence. Rather than protecting the feelings of dominant groups – namely, cisgender heterosexual men (and wealthy parents) – we must be clear about the actual patterns of perpetration and the actual dynamics of sexual violence. It makes people feel good to believe that they can prevent sexual assault by teaching college students to reduce their alcohol consumption or to be aware of their surroundings, but in reality, these strategies are not enough and they are not working – we have not seen a reduction in rates of sexual violence on college campuses in over 60 years.

We must be honest about the fact that one in 10 college men has admitted to engaging in sexual violence. These are not “strangers” to our campuses and they are most certainly not all men of color. If we admit that we have a problem, and that perpetrators of sexual violence are, in fact, members of our community, then we have a responsibility to intervene. We have a responsibility to both potential victims and potential perpetrators. Clearly, we have a responsibility to protect people from being sexually assaulted – and one really important way to do that is to intervene with potential perpetrators to stop their behavior before it starts.

Another uncomfortable truth is that not all perpetrators understand their behavior as harmful – they have been socialized to engage in sexual behavior using power. When we understand that not all perpetrators have ill-intent, yet they still cause harm to many members of our communities, we can design more effective intervention programs to serve these members of our communities as well. Stopping perpetrators from committing sexual violence will not only protect potential victims, it also restores the humanity of the people causing harm, often as a result of their own insecurities and pain.

Campus sexual violence is a complex, power-laden problem. Failing to address power – and even more specifically, perpetrators – in our efforts to reduce sexual violence is not serving anyone, and is certainly not reducing rates of sexual violence on our campuses. My experience tells me that most college students are more than ready to engage in complex, nuanced discussions about power. Maybe the problem isn’t that college students “aren’t ready” to discuss this issue from a complex lens; maybe the problem is that we educators haven’t done the work we need to in order to effectively engage with college students about this complex, nuanced problem.

Chris Linder is an assistant professor of higher education at the University of Utah, USA. She is the author of Sexual Violence on Campus: Power-Conscious Approaches to Awareness, Prevention, and Response. Follow her on Twitter @proflinder.