Claire Ainsley

Understanding the changing nature of social class is critical to understanding the different patterns of how people are voting in Britain today. Whilst commentators have struggled to draw meaningful conclusions from the last sets of election results, looking at people’s social identities can shine a spotlight on why voting seems so different today compared to its more predictable patterns in the past.

It has a lot less to do with the current state of the parties and their leaders than we imagine. And a lot more to do with the changing picture of who we are, and how we live and work.

The new working class

The changing nature of social class in Britain is at the very centre of the parties’ electoral challenges. Picturing a ‘typical’ working-class person forty years ago probably would have brought to mind a factory worker doing manual work, most likely a man, and most likely White. That has all changed. Just about every aspect of the way we work is different.

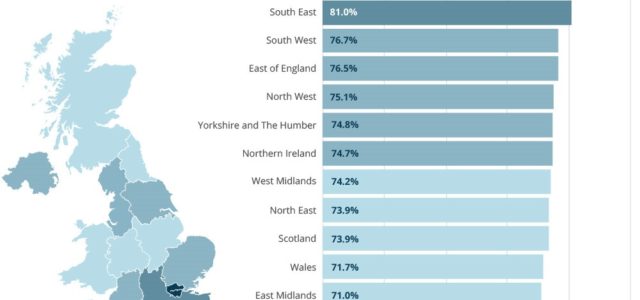

The occupations of heavy industry, which formed the bedrock of the British working class for a century, have given way to a multitude of jobs in today’s economy. Four in five jobs are now in the service sector. Many of those jobs do not pay enough for people to make a decent standard of living and meet their rising costs. And the people being employed to do them are different, too.

Today’s worker is as likely to be a woman doing shifts as a care assistant, combining earning with responsibilities at home, as it is a young man working long hours in the kitchens of a bar. If there ever was an average working-class person, there certainly isn’t now. This new working class is made up of people living on low to middle incomes, employed as cleaners, shop workers, bar tenders, teaching assistants, cooks, carers and so on. It is multi-ethnic and much more diverse than the traditional working class. The new working class is more disparate, more atomised, and occupies multiple social identities, which makes collective identity less possible. The Great British Class Survey conducted by Mike Savage and the team at the LSE provides a rich picture of the different groupings which comprise this new working class, made up of what Savage calls the traditional working class, emerging service workers, and the ‘precariat’ (a phrase originally coined by Guy Standing).

Structural changes to British society and the economy over the past four decades have created a new working class, which is very different to the traditional working class that went before it. None of the political parties have been adept enough at understanding that shift and responding politically.

Labour, the traditional party of the working class, has steadily seen its working-class vote fall, whilst support for the Conservatives has increased. In 2017, they had one of their best election results amongst working-class voters. But the overt pitch Theresa May made in Tynemouth was aimed at the traditional working class, an important, but relatively small part of the population. What political parties tend to miss is that what it means to be working class today has fundamentally changed.

And despite years of politicians focussing on middle class and ‘aspirational’ voters, even today, more people will say themselves that they are working class than say they are middle class.

Understanding the political implications of the changing nature of social class is the start of knowing what to do about it. As many other commentators have noted, public debate, politics and policy-making has been dominated by the concerns of the affluent. People who are on low and middle incomes feel much less represented in politics compared to those who are better off, which is no great surprise given they are less well represented. All of the political parties are guilty of selectively listening to voters considered to be ‘working class’, and emphasising the things that chime with their own world-views.

Winning hearts, minds and votes

My new book examines the social and political attitudes of people by income and class, and explores the key concerns for people who might be considered new working class. Broadly speaking, money and debt are top; followed by health; immigration; caring responsibilities; work; and housing. The policies that are recommended aim to address the key concerns for people who might be considered new working class, what policies might gain their support, and have some evidence behind them. What I didn’t do was ask “what do experts think” should happen for this group to improve their lives. I started with where the public is, and then brought expertise in.

It is clearly not the case that votes follow automatically from a political party making a policy commitment. A whole range of things go on for voters when making their selection: their social and political identities, and which group they associate with; how a party has performed; the character of leaders; as well as the policies. We are all emotional as well as rational beings, which is why the book is subtitled how to win hearts, minds and votes. But policies matter to people’s lives, as well as giving the voter important ‘clues’ as to who the party or leader is.

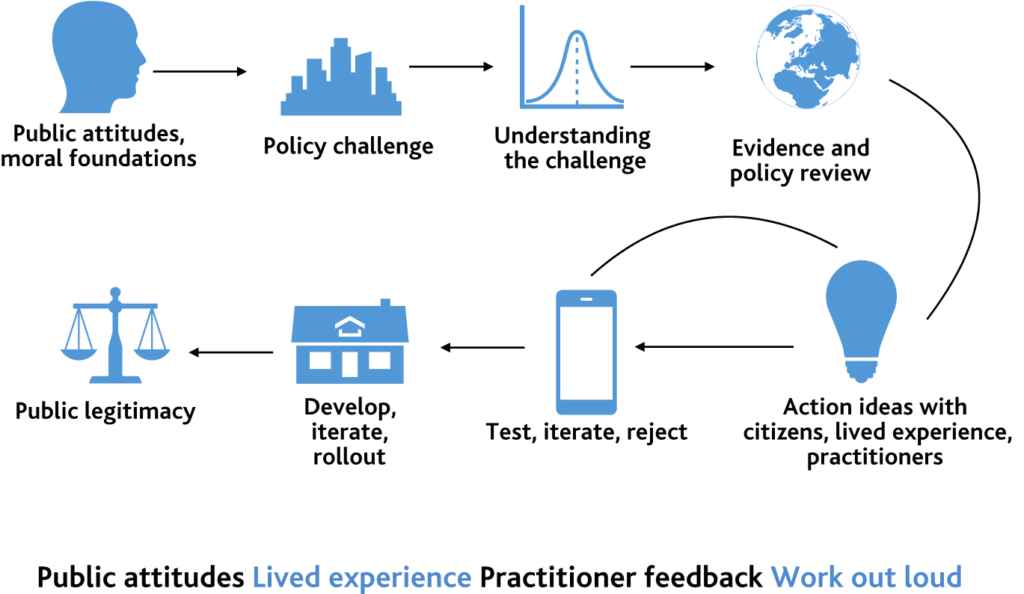

What parties need to do is understand how the voter’s social and cultural world shapes what they think, and in the book, I use the moral foundations put forward by Jonathan Haidt to suggest how parties can trigger the right emotions in voters through their policy choices. Rooting policy in public attitudes not just tells a party which policies might be likely to win them votes at election time, but which important policies may need a longer run-in to warm the public up.

So what kinds of policies does taking this approach mean that you arrive at? I used the data that the think tank Policy Exchange collected on people’s values, which was part of the work that went on to form the case for focussing on the ‘Just About Managing’ classes. It shows that amongst all groups, the public have four top values: family, fairness, hard work and decency. So I grouped the policies around these values.

Policies such as a day one employment rights charter for all would indicate a party’s commitment to fairness and offer protection to workers. Making good work the goal of industrial strategy, with greater political and economic devolution, would demonstrate a party’s leadership on hard work. A statutory Family Test that, backed up by family policies such as state-backed guarantees on health and preschool education, would signal that a party stood by families. And a modern set of British values to tackle discrimination and promote social integration would show to voters that it stood for decency.

Public attitudes-led policy making model

The book proposes a new model of public attitudes-led policy-making (Ainsley, 2017), as a means to strengthen the legitimacy and relevance of policy-making to people’s lives. Politicians should not just introduce policies because public support indicates they are popular, nor avoid policies because there is no public support. But starting with what the public think – not just the new working class – does suggest what the priorities should be, what they public’s views are, what the likely vote winners are, and demonstrates where ground needs to be laid for important, but less popular policies. Policy is more likely to stick for the long-term if there is public will to support it, therefore grounding policy-making in public opinion as well as evidence allows the public to see policies being implemented which reflect their concerns, in addition to representing good value for money, because evidence suggests they are what will be effective.

However, public attitudes-led policy making has to be conducted within a framework of positive values, otherwise the risk is that politicians bend to the whim of public opinion. Politicians’ attempts to tackle one of the issues people raise – levels of immigration – appear to have shown no awareness of how in pandering to one, narrow group; they completely alienate other groups who are also part of this new working class. There also has to be positive steps taken to close the ‘participation gap’ so that existing societal and political inequalities are not exacerbated. But the prize could be a new way of connecting expertise and democracy.

For all of the insightful attempts to understand the electoral dividing lines in electoral patterns, nothing beats social class for its explanatory power in British politics. While elections cannot be won on this new working class alone, as parties must build coalitions in order to win power, understanding the values, attitudes and interests of this new working class is now critical to success in British politics.

More than anything this book is an appeal to the political parties to listen to the concerns of these voters, and act on them. With warning signs across Europe and the United States about the failure of democracies to adapt to societal and economic change, the need has seldom been more urgent. By bringing together public attitudes, user experience, and expertise, policy-making in modern democracies could provide a powerful alternative to a rise in populist approaches.

Claire Ainsley is Executive Director of the independent Joseph Rowntree Foundation, member of the advisory board of the Centre for the Study of British Politics and Public Life, and a member of the executive committee of the Political Studies Association. ‘The New Working Class: how to win hearts, minds and votes,’ was published by Policy Press in May 2018 and was written in a personal capacity.