Hilary Aked

This article examines the interactions between counter-extremism policies in the UK, Germany and France on the one hand, and the far right Islamophobic ‘counterjihad’ movement in each country on the other. Its starting point is Arun Kundnani’s observation that while considerable attention has been paid to the relationship between government narratives and ‘Islamist extremism’, as well as to so-called ‘cumulative extremism’ – the allegedly mutually reinforcing phenomena of far right and Islamist extremism – there is very limited scholarship on how government narratives and practices impact on the far right, and vice versa.[1] The article argues that although official counter-extremism policies in different countries exhibit specific geographical inflections, in every case these policies have proved amenable to the agenda of counterjihad actors. Illustrating this are examples of counterjihadists adopting the language of ‘counter-extremism’ as a cover for racism. While it is commonplace to hear of Islamophobic ideas from the far right being ‘mainstreamed’, this suggests that narratives also travel in the other direction and raises questions about whether counter-extremism policies may in fact foster this strand of the far right.

Some analysts have begun to speak of ‘two fascisms’ in contemporary Europe: one traditional faction committed to anti-Semitism, and another, newer, bloc focused on Islamophobia.[2] The latter strand – the so-called ‘counterjihad’ movement – combines Islamophobia with virulent anti-immigration sentiment, twin preoccupations embodied in the idea of ‘Islamisation’ (which French sociologist Raphaël Liogier calls a ‘fantasy of reverse colonialism’). Counterjihadism has grown in the last decade in numerous western countries, particularly the US and northern Europe and, as its name suggests, takes its cue from the war on terror, positioning itself in opposition to political violence supposedly carried out in the name jihad. Why has the counterjihad movement flourished in the era of counter-extremism? Evidence from the UK, Germany and France points to synergies between counter-extremism and counterjihadism in the reproduction of Islamophobia.

Counter-extremism programmes like the UK’s Prevent strategy are product as well as progenitor of Islamophobia. Originally, Prevent funding was distributed according to a crude algorithm which used the size of a region’s Muslim population as a proxy for the threat of extremism; as such, its implementation treated Muslims from the outset as a ‘suspect community’.[3] A key early example was Project Champion in Birmingham, a 2010 initiative through which hundreds of cameras were installed in two Muslim areas of the city, secretly financed with £3 million from the Association of Chief Police Officers’ Terrorism and Allied Matters fund. Police called the project ‘the first of its kind in the UK that seeks to monitor a population seen as “at risk” of extremism’. This emphasis on Islam has not changed, as became made clear in 2016 when it emerged that the opaque Research Information and Communications Unit was using a network of Muslim civil society organisations to covertly disseminate government propaganda, believing it would reach its targets – Muslim communities – if delivered by apparently credible messengers.

While ‘other forms of extremism’ have long been rhetorically acknowledged in UK counter-extremism narratives,[4] the far right has always been a secondary concern, presented as an isolated phenomenon. Despite serious Islamophobic violence, few practical measures have been implemented to undermine it compared to the sprawling surveillance and propaganda regime targeted at Muslims. On the contrary, the unprecedented climate of suspicion and mistrust created by legislation like the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015 – which seeks to turn public sector workers into informants – appears to have provided a fertile atmosphere in which the paranoid conspiracy theories of the counterjihad movement have grown.

In 2015, ex-leader of the English Defence League street movement Stephen Yaxley-Lennon (aka Tommy Robinson) told a newspaper that the city of Birmingham, home to the UK’s biggest Muslim population, had been chosen as the site of a protest because it was ‘where most of the terrorists have been from’. This logic merely mimicked – albeit more bluntly – the diagnosis made by government five years earlier when it sought to implement Project Champion and made explicit the rationale implicit within it. That erstwhile state-sponsored think tank the Quilliam Foundation was revealed to have channelled money to Yaxley-Lennon also speaks to the ideological overlap between official counter-extremism and counterjihadism. Quilliam claimed this money was to help Lennon quit the far right scene. But soon afterwards he was involved in launching new counterjihad projects like the short-lived outfit VOICE (‘Victims Of Islamic Cultural Extremism’), set up in 2015 by counterjihad activist Anne Marie Waters. Tellingly, VOICE styled itself as a counter-extremism body, declaring its opposition to ‘left and right wing extremists’. In doing so, it was not unique. The now defunct Stand for Peace also found that a self-appointed counter-extremism mandate got it taken seriously by the British media, distracted from the extreme right views of its founder Sam Westrop, and provided a respectable language for targeting Muslims.

In Germany, the internal national intelligence agency groups ‘extremism’ into three categories: right wing, left wing and Islamist. Conscious of modern history, the German government places more emphasis on opposing the far right than in the UK or France. However, such initiatives are heavily focused on combating neo-Nazism and neglect counterjihad actors. There are notable contrasts, too, in how the far right and those labelled Islamists are treated. For instance, a government ‘de-radicalization’ program focused on Muslims called Hayat (Arabic for ‘life’), was modelled on EXIT-Deutschland, an initiative ‘to help anyone who wants to break with right-wing-extremism’. However, while individuals self-refer to the latter programme, Hayat works almost exclusively with information provided by families, friends, teachers or employers of potentially ‘radicalised’ Muslims. The ‘Islamist threat’ is emphasised by authorities as the gravest, while the official line of the Federal Bureau for the Protection of the Constitution is that right-wing extremism in Germany is declining. This seems misplaced. In fact, it is merely changing shape.

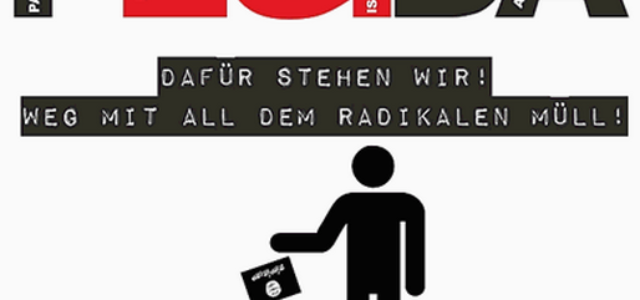

The PEGIDA (Patriotic Europeans Against Islamisation of the West) movement illustrates this. Downplayed by Saxony Interior Minister Markus Ulbig – who said ‘there are many middle-class citizens among them… you can’t toss them all into the same Neo-Nazi pot’ – PEGIDA does indeed represent a different strand of far right politics but a far more insidious one. It packages its counterjihadist message in the supposedly even-handed language of liberal counter-extremism. Its leaders have declared their movement opposed to ‘preachers of hate, regardless of what (sic) religion’ and ‘radicalism, regardless of whether religiously or politically motivated’. Indeed, in a clear nod to the German government’s approach – rejection of Islamist, left wing, and right wing extremism (predominantly understood as neo-Nazism) – PEGIDA’s logo depicts the ISIL flag, the Communist hammer and sickle, the Anti-Fascist Network logo and the Nazi Swastika being thrown in a dustbin together; the accompanying slogan reads ‘Away with all the radical trash!’ As in the UK, other German counterjihad groups style themselves as ‘counter-extremism’ bodies too. The Stresemann Stiftung describes its namesake Gustav Stresemann (leader of the German People’s Party, 1918–1929) as a ‘great statesman’ who ‘understood the necessity of shielding Germany from extremist forces from the left as well as from the right’.

The French government has also intensified its efforts to counter ‘radicalisation’ in recent years. In January 2015, a propaganda campaign explicitly focused on Muslims, with a name echoing that of the counterjihad movement – ‘Stop Djihadism’ – was launched. Soon afterwards, an anonymous hotline – Numero Vert – was introduced. Families, friends and neighbours of suspected ‘extremists’ were encouraged to call. Francesco Ragazzi of Sciences Po in Paris argues that such initiatives contributed to ‘an atmosphere of suspicion’. More concretely, extensive abuses of civil liberties by the authorities were documented under the prolonged état d’urgence. Immediately after the November 2015 Paris attacks Interior Minister Bernard Cazeneuve shut down three mosques, on grounds of ‘radicalisation’, effectively endorsing collective blame for the attacks. At least 20 more closures followed. To some extent, this granted social license to the likes of far right activist group Génération Identitaire who have also frequently targeted mosques.

Meanwhile, the names chosen by two other French counterjihadist groups – Résistance Républicaine and Riposte Laïque – highlight the ease with which ‘French values’ like Republicanism and the concept of laïcité (secularism), are weaponised and put to work in the service of an Islamophobic agenda. On the rhetorical level, therefore, such groups speak the same language as the state and frame the causes of – and solutions to – Islamist political violence in a similar way. In the context of this convergence between government and far right, the Front National has flourished and – despite its anti-Semitic roots – Marine Le Pen’s quest to sanitise the party has allowed it to puncture the cordon sanitaire, which previously kept it relatively quarantined.

Bearing in mind that ‘fascism acquired respectability as a counterweight to Bolshevism’,[5] we should pay attention to the way in which far right movements are empowered by government counter-extremism policies which legitimise Islamophobia and institutionalise discrimination. The slipperiness of highly racialised concepts like ‘extremism’ is such that many counterjihad groups find ‘counter-extremism’ provides a respectable vocabulary with which to express their racism. Counter-extremism frameworks invite us to see any ideology besides liberalism as merely one expression of a single phenomenon, ‘extremism’, (while remaining, in practice, hyper-sensitive to Islamism). As Liz Fekete notes, a false equivalence is thus drawn between a range of opposing political ideologies, political violence is abstracted from its historical context and – by treating the government as neutral – the increasing authoritarianism of state power in the era of the war on terror is overlooked.

The dynamic interactions between counter-extremism and the counterjihad movement suggest a symbiotic relationship. Given that the former have created space for the latter to advance, it is misguided simply to call on government – as one academic does – to ‘get tough on extremism in all its forms’. Existing counter-extremism practices and their genealogy point to an in-built bias; they should therefore be rejected wholesale. Meanwhile, the far right continues to thrive in a climate of officially sanctioned suspicion and, contrary to some claims [6], does not eschew electoral politics (as the success of Alternative für Deutschland in Germany and Geert Wilders’ Freedom Party in the Netherlands shows). Indeed, working through the state is made easier by the presence of counterjihad actors embedded within the political elite, notably the likes of Baroness Cox and Lord Pearson in the UK. In the long run, the far right – especially with its hands on the levers of state power – could pose a far greater threat to the fabric of society than the still-small number of violent Islamists with whom government and media remain preoccupied.

References:

[1] Kundnani, A., (2012) Blind Spot? Security Narratives and Far-Right Violence in Europe, The Hague: International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, 11.

[2] Fleischer, R., (2014), ‘Two fascisms in contemporary Europe? Understanding the contemporary split of the Radical Right’ in In the Tracks of Breivik: Far Right Networks in Northern and Eastern Europe, eds. Deland, M., Minkenberg, M. and Mays, M. Münster: LIT Verlag, 53-70.

[3] Kundnani, A. (2009) Spooked! How Not to Prevent Violent Extremism, London: Institute of Race Relations.

[4] For example, see: Home Office (2011) Prevent strategy, HM Government, 57.

[5] Kundnani, A., (2014) The Muslims are Coming! Islamophobia, extremism, and the domestic war on terror, London: Verso, 101.

[6] Goodwin, M., Cutts, D. and Janta-Lipinski, L. (2014) ‘Economic Losers, Protesters, Islamophobes or Xenophobes? Predicting Public Support for a Counter-Jihad Movement’, Political Studies, 64(1), 4–26.

Hilary Aked is a freelance writer and researcher and holds a PhD in political sociology from the University of Bath. This article is based on research conducted for the Open Society Foundation-funded project ‘Curtailing the counterjihad project’ and the forthcoming Spinwatch / Public Interest Investigations report ‘Islamophobia in Europe: counter-extremism policies and the counterjihad movement’.