Stefanie Walter

The ongoing Brexit-negotiations have been difficult and fraught, with hard positions on both sides. The British government has been particularly frustrated by the hard negotiating line pursued by the EU under the lead of Michel Barnier, and the unusual degree of unity among the EU-27 in support of the EU’s Brexit negotiation strategy has surprised quite a few observers.

Of course, this unwillingness of EU-27 governments to break ranks has a variety of sources. One explanation, however, that has received relatively little attention so far is public opinion in the remaining member states. Surprisingly, although there has been extensive polling on what the British public thinks about Brexit, there has been much less focus on the Brexit-views of Europeans in the remaining member states.

To improve our understanding of what voters in the EU-27 think about Brexit and the Brexit negotiations, this article presents evidence from an EU-wide online poll designed by myself and conducted by Dalia Research for the University of Zürich in July 2017. The sample consists of 9371 working-age respondents (ages 18-65), drawn across the remaining 27 EU Member States, with sample sizes roughly proportional to their population size.

This data shows that Brexit is an issue that a majority of Europeans care about: 46% of the Europeans surveyed said that they followed Brexit a little, and 18% expressed a strong interest in Brexit (compared with 42% and 37%, respectively, in the UK). To the extent that domestic public opinion constrains the negotiation space of the EU-27 governments, it is thus worthwhile to examine what EU-27 citizens think about Brexit.

To this end, I will focus on three questions:

• Does the EU public support the hard negotiating stance pursued by the EU in the Brexit negotiations?

• How do EU citizens evaluate the effects of Brexit on the UK, the EU, and their own country?

• To what extent do spillover effects exist between the Brexit negotiations and exit preferences in other member states?

Does the EU public support the hard negotiating stance pursued by the EU in the Brexit negotiations?

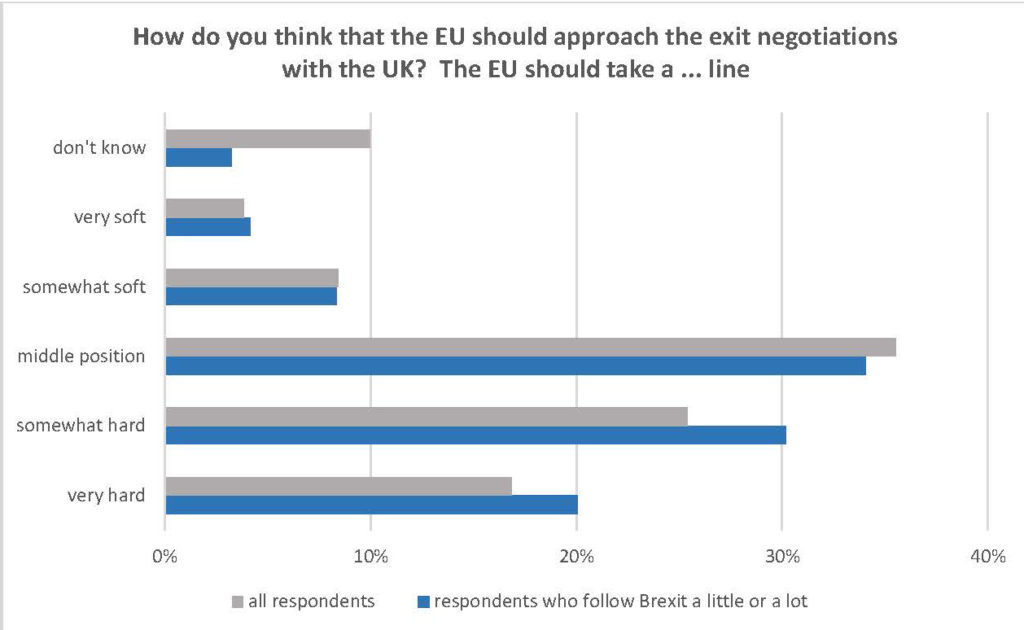

Overall, the European public seems to agree with the uncompromising line of the EU Commission on Brexit. A plurality of respondents (42%) favor a somewhat or very hard line. This means that they think the EU should insist that the UK pay a large “exit bill” to compensate the EU for the costs of Brexit, guarantee special rights for EU citizens living in the UK, and should not give the UK privileged access to the European Single Market. The preference for a hard stance increases the more interested respondents are in Brexit. Among those who follow Brexit a lot, almost two-thirds (62%) support a hard line. In contrast, only 12% of respondents think that the EU should approach the exit negotiations with the UK with a soft line, defined as accepting a small “exit bill,” limits on the rights of EU citizens currently living in the UK, and privileged access for the UK to the European Single Market.

Figure 1: Public opinion on the EU negotiation strategy in the Brexit negotiations

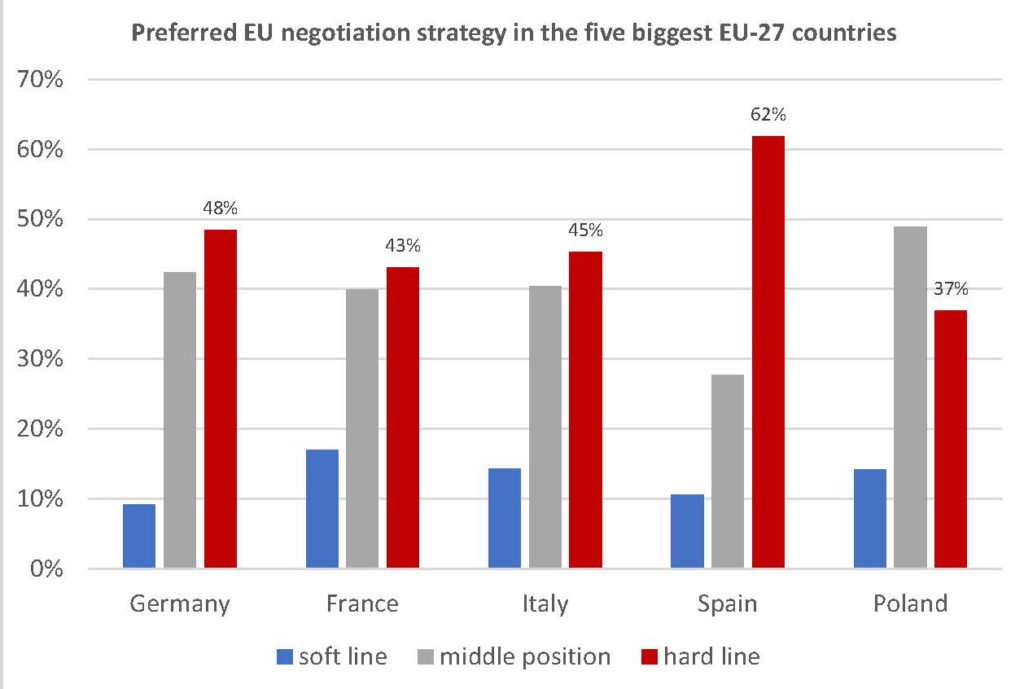

Despite some differences across countries, the support for a hard negotiating position is also strong when we look at individual countries. Figure 2 shows the results for the five largest EU-27 countries. Support for a soft line is low in all of them, and with the exception of Poland, a hard line is the most popular negotiation strategy. Among those who are interested in Brexit a lot, those in favor of a hard line even constitute a majority in all five countries, including Poland. Moreover, contrary to the hope of some leading Brexiteers that Germany and Spain would lobby in the UK’s favor lest jobs in the German car or Spanish tourism industry be lost, the German and especially Spanish public is taking a rather hard line: 48% of German respondents and 62% of Spanish respondents support a somewhat or very hard EU position in the Brexit negotiations.

Figure 2: Preferred EU-negotiation strategy in the five largest EU-27 states

These findings suggest that rather than representing an EU-run-amok, the current EU negotiating strategy pursued by Michel Barnier is based on a broad consensus among the EU public. From this perspective, it is not surprising that British attempts to bypass the EU institutions by appealing directly to EU leaders have failed, or that Brexit is not a highly contested issue in these countries.

How do EU citizens evaluate the effects of Brexit on the UK, the EU, and their own country?

The economies and societies of the UK and the remaining 27 EU member states are strongly intertwined. Brexit will thus inevitably affect everyone involved in the Brexit process: the UK, the remaining member states, and the EU as such. How does the EU-27 public assess these effects?

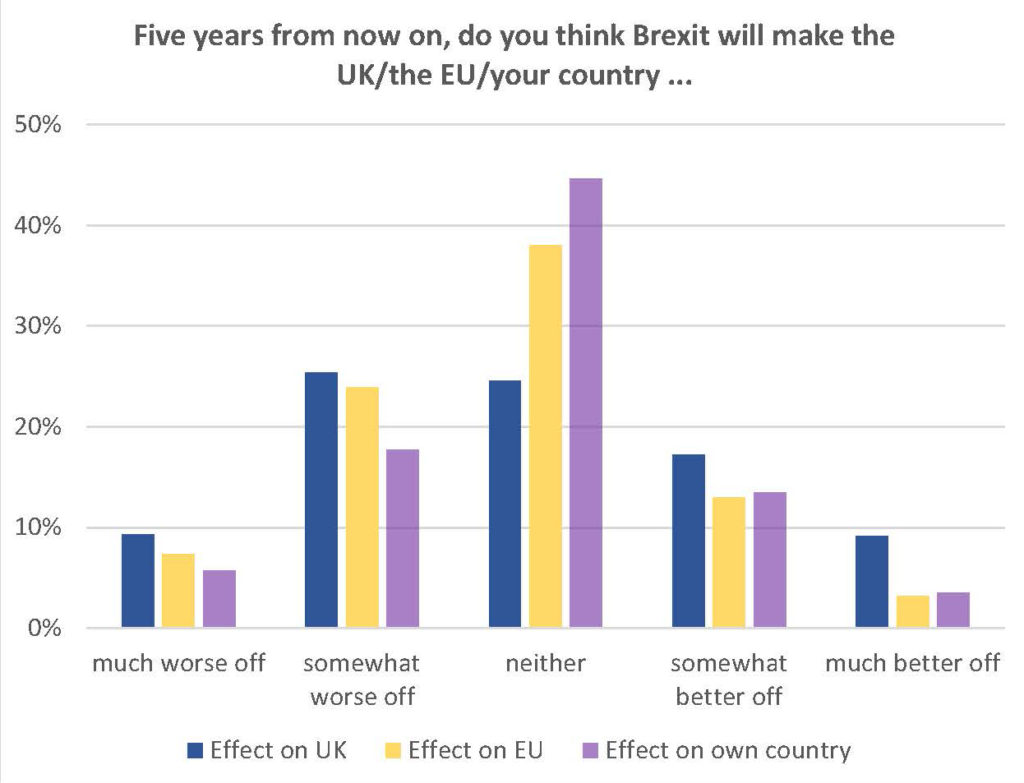

Figure 3 shows what respondents think about the medium-term consequences of Brexit. Three findings stand out. First, many Europeans do not think that Brexit will bring significant changes over the next five years, especially not outside the UK. Less than 20% of respondents think that Brexit will make the UK, the EU, or their own country much worse or much better off. Second, many Europeans are oblivious to their own country’s vulnerability to Brexit. 44% think that Brexit will neither benefit, nor hurt their country, and this rate is the same among those with a strong interest in Brexit. This suggests that public opinion on Brexit could still shift quite a bit as the effects of Brexit become clearer to voters. Finally, to the extent that they do expect Brexit to have an effect, more people see these effects as negative for everyone involved. Nonetheless, a significant number of respondents also see upsides to Brexit, notably for the UK itself.

Figure 3: Expected medium-term effect of Brexit on the UK, the EU, and respondents’ own country

Note: The percentages do not add up to 100; the rest are don’t knows

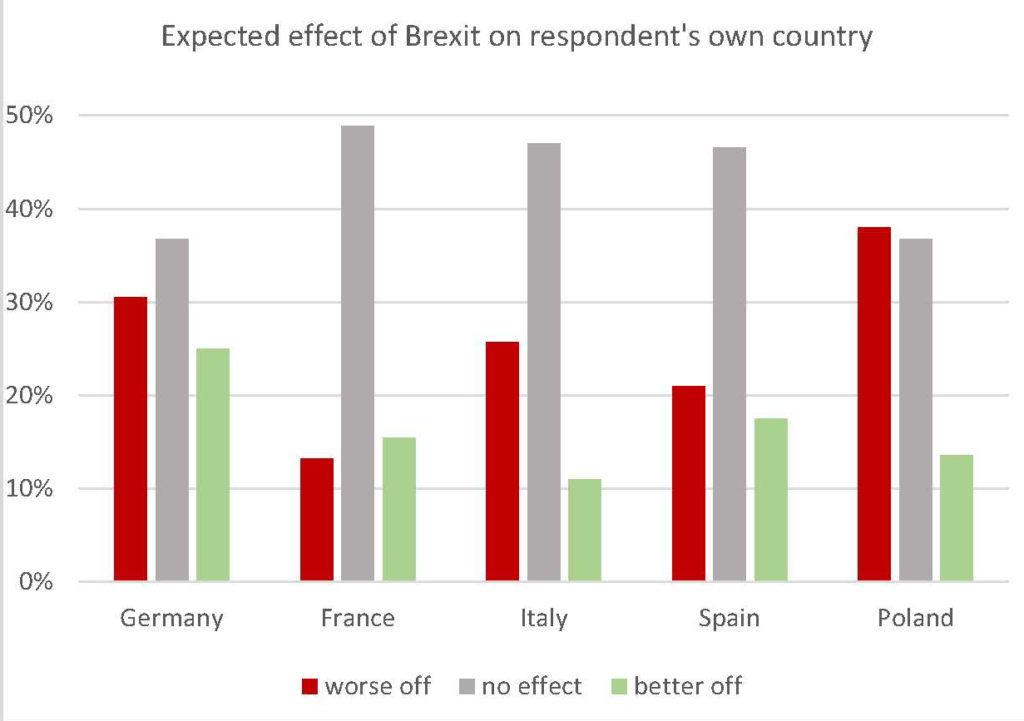

Yet this also masks considerable differences among the EU member states. Figure 4 shows that in some countries, such as Poland and Germany, the public is quite aware of the possible negative consequences and opportunities of Brexit for their own country. In other countries, such as France, the opinion that Brexit will not have much effect on the country’s future dominates.

Figure 4: Expected medium-term effect of Brexit on the five largest EU-27 member states

To what extent do spillover effects exist between the Brexit negotiations and exit preferences in other member states?

Voters’ expectations about the effects of Brexit matter for the Brexit negotiations because they widen or constrain policymakers’ room to maneuver. But they also matter because these expectations (and eventually, the actual trajectory) are likely to feed back into their own assessments about the viability of leaving the EU.

In the negotiations with the UK, the EU-27 governments therefore face an “accommodation dilemma”: In principle, as many Leavers rightly emphasize, the EU-27 have strong incentives to grant the UK continued access to the EU’s single market in order to minimize the disruptions of Brexit at home. Yet if this accommodation of the Brexit-vote creates incentives for other countries to leave as well, such a response might put the entire European project at risk in the long run. After all, a sizeable proportion of Europeans (28% in my data) say that they would vote to leave the EU if their own country were to hold an EU-exit referendum

The rationale for the current hard, non-accommodation strategy vis-à-vis the UK is thus rooted in the hope that such a hard line will discourage further efforts at disintegration. But is this hope warranted?

In a final analysis, I examine how respondents’ views about the likely consequences of Brexit for the UK are related to their likelihood of voting leave in a potential exit referendum. Figure 5 shows that those who are more pessimistic about the effects of Brexit for the UK are between ten and twenty per cent less likely to vote in favor of leaving the EU. In contrast, those who are more optimistic about Britain’s prospects outside the EU are much more likely to support an EU-exit of their own country. Notably, this analysis takes into account respondents’ general opinion of the EU – even among respondents with a similar opinion of the EU, differences in expected effects of Brexit translate into different propensities to vote leave.

Figure 5: Expectations about the effects of Brexit for the UK and potential leave-vote

Because this relationship is most pronounced among those with a negative or neutral opinion of the EU, this suggests that the accommodation dilemma is real. A hard Brexit will hurt the member states. But the remaining EU-27 governments also face the risk that allowing the UK to have its cake and eat it, too, and to prosper as a result, risks a profound destabilization of the EU.

What is the effect of the Brexit negotiations on eurosceptic elites in other countries, such as Switzerland

The accommodation dilemma matters not only within the EU, but also for the EU’s relationship with other countries who would like to redefine their relationship with the EU. The most prominent example is Switzerland. After Swiss citizens voted in a referendum in February 2014 to end “mass immigration” into the country, the Swiss government tried to renegotiate its bilateral treaty with the EU on the free movement of persons. The EU’s position was very hard, however – in fact, the EU Commission declined to even enter official negotiations. Ultimately, Switzerland implemented the referendum vote in a way that did not infringe on the free movement of people. Switzerland’s largest party, the populist right Swiss People’s Party has vehemently protested against this strategy, however, and recently unveiled a new initiative for a popular referendum that would force the government outright to terminate the bilateral treaty on the free movement of persons with the EU. The proponents of this initiative are convinced that if the government only negotiated hard enough with the EU, the EU would yield. In that sense, Brexit is an insightful test case that is closely watched in Switzerland. The accommodation dilemma is also relevant for the EU-27 countries with regard to countries such as Switzerland.

Public opinion on Brexit thus matters. But although British public opinion on Brexit is much more closely scrutinized than that in the EU-27, public opinion in the remaining member states will matter as much – or even more – for the Brexit negotiations.

Stefanie Walter is Full Professor for International Relations and Political Economy at the University of Zurich. Her research focuses on topics related to globalization, international financial crises, and public opinion. She is the author of “Financial Crises and the Politics of Macroeconomic Adjustments” (2013, Cambridge University Press).

Image Credit: succo

* A previous version of this article was published on the LSE Brexit blog