Diane Reay

In Education and the Working Class, written in 1962, Jackson and Marsden argued that: The educational system we need is one which accepts and develops the best qualities of working class living and brings these to meet our central culture. Such a system must partly be grown out of common living, not merely imposed on it. But before this can begin, we must put completely aside any earlier attempts to select and reject in order to rear an elite (Jackson and Marsden 1962: 246). In 2017 we are no nearer to trying to put aside earlier attempts to select and reject in order to rear an elite than we were in the 1960s. In fact, there has never been a time in England when an individual’s inherent value can be disentangled from their class position.

This differential valuing of the upper, middle and working classes not only infuses the educational system, it has shaped its structure, influenced its practices, and dictated the very different relationships social classes have to the system since the establishment of state education for all in 1870. It would be hard to portray working class experiences in education as generally fulfilling, as about ‘bettering oneself’ in the classic middle class mode. The working class experience of education has traditionally been one of educational failure not success.

Central to working class relationships to state schooling is that it is not their educational system. The system does not belong to them in the ways it does to the middle classes and they have little sense of belonging within it. In place of middle class enthusiasm for school based learning there is more often a pragmatism and strong remnants of historically rooted attitudes to education that recognize at an important level that the educational system is not theirs, does not work in their interests, and considers them and their cultural knowledge as inferior. The concept of the ‘left behind’ has gained popular currency since the Brexit vote but the working classes have always been left behind in English education.

It is this historical legacy that still over-shadows our contemporary educational system. But the inequities it generates have been reinforced by the neoliberal drive towards markets, regulation, individualism, and increased competition. In 21st century England Education has become a business, it is no longer seen as a service the state provides for its citizens at collective expense. The same stealth process of privatisation that has beset the NHS already has a stranglehold on English state education. From school buildings and playgrounds that have been sold to multinational property companies to Academy chains providing Free school places at over fifty per cent of the cost of a state maintained school place, c (Johnson and Mansell 2014). English Education is becoming increasingly fragmented and atomised with a diminishing sense of collectivity and collaboration.

This applies not only to relationships between schools, but also those within classrooms. Over the last 30 years, UK politicians and policy makers have seemed intent on moving away from educational approaches, such as collaborative teaching and learning methods and mixed attainment grouping, that work towards those that don’t. We have been bombarded with a plethora of educational policies such as standards, testing regimes, league tables, school choice, academies and free schools, the return to traditional models of both primary and secondary curriculum, performance and managerialism, academic and vocational streaming, punitive strategies such as naming and shaming of schools, and a preoccupation with ‘school improvement’ and ‘school effectiveness’ (Smyth and Simmons 2017), all of which have had little or no impact on educational inequalities, and many of which have increased children’s stress and reduced their levels of wellbeing.

As a result, the contemporary English school system is profoundly unjust and creates demoralisation, demotivation and physical and mental distress among all children, but particularly the majority of working class children who are positioned as ‘losers’ in a hyper-competitive educational environment. The damage is different in appearance and texture to that suffered by Jackson and Marsden’s generation, but its scale and intensity has not diminished. The way class works in education has shifted and changed, but the gross inequalities that are generated through its workings do not change.

The impetus for my new book, Miseducation: inequality, education and the working classes, was to talk to children, young people, and their parents in order to understand what has changed and what has remained the same since Jackson and Marsden wrote ‘Education and the Working Class’. The most troublingly continuity is that most working class children and young people experience education as failure. I try to explain why this is still the case in the face of so many policy initiatives to improve working class educational attainment. I argue that in place of ‘the usual suspects’, namely either working class culture or ‘failing’ schools that invariably have predominantly working class and BAME intakes, we need to focus on the operations of power within education. This involves looking at relational aspects of educational achievement, and examining the actions and attitudes of the middle and upper classes as well as those of the working classes. It also requires an historical contextualized perspective that recognizes over a century of class domination within state schooling, and the symbolic power of the private sector which continues to be held up as embodying all that is best in English education.

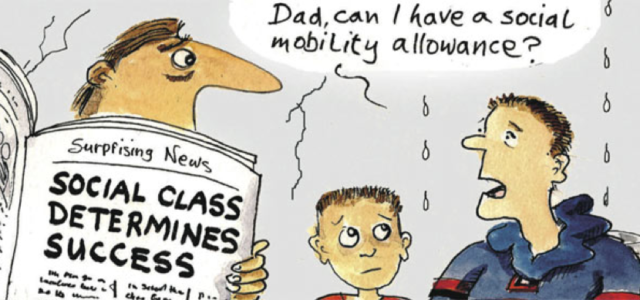

Getting low grades in your SATs, low marks in a test, being placed in a bottom set, or simply receiving little attention, and in particular, little praise, all conspire to make the working class experience of education one in which success is, at best, tenuous and failure often feels inevitable. Once this would have been seen as a problem the whole of English society, and especially those who govern it, need to address. Now, it is viewed as the fault of the working class individual as working-classness is viewed as a matter of internal traits rather than economic position. As a result, class inequalities become just the natural order of things because working class individuals who fail to be socially mobile are seen to lack the right qualities rather than sufficient resources.

An irony, is that at an historical juncture when social mobility has stalled, it has become the ‘holy grail’ of education. But whereas, in the 1960s, passing the 11-plus was emblematic of working class social mobility now moving on to higher education is seen to represent working class educational success. As we have moved to a mass system of higher education, the logic of the educational ladder has simply moved upwards. Instead of the 11-plus operating as a mechanism of social selection it is our elite universities who have taken over this role. Elitist processes masquerading as meritocracy are just as evident in the English educational system as they were 60 years ago, but the primary engines of this pseudo meritocracy are no longer the grammar schools but the elite universities.

The working classes did not have a fair chance in education when Jackson and Marsden were writing, and they definitely do not have one in a 21st century England scarred by growing inequalities. The rhetoric of equality, fairness and freedom in education has intensified since the beginning of this century but it has done so against a back-drop of ever-increasing inequalities, the entrenchment of neo-liberalism, and class domination. It is predominantly babble, signifying little, and certainly nothing that will make any contribution to a fairer, more equal educational system. England has become an intensely aspirational society in which parents are expected to strategise and invest in order for their children to have a better ‘fair chance’ than other people’s children.

As Stefan Collini (2010) argues, such a focus on aspiration is not progressive but reactionary ‘a symptom of the abandonment of what have been, for the best part of a century, the goals of progressive politics’. We have allowed the structural conditions of a deep social, political and economic crisis to be defined as a problem of individual behaviours. The costs and cruelties of this ideological displacement are disturbingly evident in the young working class students’ accounts of always having to do better, to be better, and in the system’s judgment that, in the vast majority of cases, their efforts and striving are not good enough. We need to develop a different sort of aspiration – collective rather than individualised, expansive rather than narrowly conceived – an aspiration that nurtures and grows out of a sense of collectivity, collective responsibility, and openness and respect for difference. Then and only then will we be making a progressive move towards realising the potential of all children rather than the select few.

References:

Jackson, B., and D. Marsden. (1962) Education and the Working Class. London: Penguin Books.

Johnson, M and Mansell, W (2014) Education not for sale: A TUC research report. London: Trades Union Congress.

Reay, D (2017) Miseducation: Inequality education and the working classes Bristol: Policy Press.

Collini, Stefan (2010) ‘Blahspeak’, London Review of Books, 32(7), 7-8 April, pages 29-34.

Smyth, J and Simmons, P (2017) ‘Where is class in the analysis of working class education?’ in Smyth and Simmons (eds) Education and Working Class Youth, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Diane Reay is Professor of Education at Cambridge University.

Image credit: Copyright, Ros Asquith, used with permission