Amanda Sacker and Christine Garrington

Just over a year ago the Prime Minister and the NHS promised the biggest transformation of mental health care in a generation, pledging to help more than a million extra people and to invest more than a billion pounds a year by 2020/21. With one in four people experiencing a mental health problem in their lifetime and the cost of mental ill health to the economy, NHS and society slated at £105bn a year, it’s clear why this has become one of the most pressing issues of our time.

It is time to invest properly in mental health. We need to put it on a par with our physical health and to listen carefully to the emerging evidence on how closely the two, together with our social environment, are intrinsically and inescapably intertwined over the lifecourse. Failure to do so will see an ever-growing crisis worsen, whilst partially and poorly informed efforts to tackle the issue will most likely fail. Many of the social stigmas surrounding people’s struggles with mental health may have been eroded in recent years, yet our ability and capacity to treat people within our healthcare system has not kept up, with only a quarter of people suffering from a common mental health disorder receiving treatment.

The Royal College of General Practitioners believes that GPs are best placed to deliver effective and efficient mental health services, but say a lack of investment, support and training is partly to blame for the failure to tackle the stark inequalities. Simon Stevens, Chief Executive of NHS England agrees that mental health services have been the NHS’ poor relation. A body of research undertaken by and with colleagues at the ESRC International Centre for Lifecourse Studies (ICLS) at UCL shows that we need to be thinking about a person’s mental health even before they are born if we are to stem this tide. It strengthens the case for immediate action and offers some areas of focus for consideration.

Under the skin

First, the research shows that the extent of emotional disorders has increased over time, particularly among young women. Seventeen per cent of 16- to 24-year old women suffered from emotional distress in 1991, increasing by an average of 0.2 per cent per year since then.

Our work gets right under people’s skin, looking at objective measures of health together with their social circumstances. This has helped us to identify a link between a stressful early life and the existence of the so-called “stress hormone” cortisol in adulthood. Cortisol levels change over the day – the general pattern is for relatively high levels on waking that reach a peak about 30 min later, followed by a decline across the day to reach a minimum about 4 hours after going to sleep. Stress alters the pattern of cortisol changes throughout the day. We have established that in adults who were separated from their mother in childhood for a year or more, the cortisol hormone is about 20 per cent higher.

When we looked at deaths among the same group of adults five years later, those whose cortisol levels did not decline as much over the day were 11 per cent more likely more likely to have died, particularly from heart disease. So we have clear evidence of the links between stressful events in childhood and their negative health effects more than 5 decades later.

Transmitting mental health problems

Mental health can also be a problem for us even when we are not the ones exposed to the stress; if our mother is exposed to racism for example. Information from the Millennium Cohort Study, which has followed 20,000 children born between 2000-2002, shows that, when their child was aged 5, almost a quarter of ethnic minority mothers had suffered verbal racial abuse in the previous 12 months.

By the time the child was 7, their mother’s mental health had deteriorated and by age 11, the child’s own socioemotional development had been negatively affected.

Perhaps parents who suffer racism are less able to provide the sort of supportive and nurturing environment a child needs to thrive and do well. Or it could be that children become more aware of racism’s effects on their mother as they approach adolescence. We can say with some confidence that racism towards a mother is strongly linked to poor mental health outcomes not only for her, but for her children too. In this way, mental health problems are transmitted from one generation to another.

This is food for thought in a highly charged political and social climate where incidents of hate crime have increased and fears are being expressed of a further backlash against EU Citizens when Article 50 is triggered. Sticks and stones do indeed break bones and harsh words can break minds it seems. The message that racism is not only upsetting, but seriously damaging to our children’s life chances must be heard and acted on.

Time for bed

For parents trying to help their child grow into a physically and mentally robust teenager and adult, we have some scientific evidence that we think is simple to act on. Give your child a regular bedtime and try to read with them as often as you can!

Our findings show that children with later and irregular bedtimes read less well, do worse at maths, have less good spatial abilities and have poorer behaviour. These effects are cumulative and, if left unchecked, likely to have negative mental health consequences later on. Changing a child’s bedtime from late or irregular to regular led to an improvement in their behaviour, whilst a change from a regular to an irregular bedtime saw a deterioration, so it’s not too late to make a change and set your child on a healthier, happier path. Reading to a child is closely linked to their emotional as well as their cognitive development. 3 year-olds who are read to less than once a week are nearly four times as likely to have a range of emotional problems.

Once again the social, physical and mental are closely intertwined, as the researchers believe that the physical closeness and interactions that take place when parents and children read together play a role in regulating stress responses. For policymakers, charities and businesses looking to work to support ‘hard-pressed’ and ‘troubled’ families and to improve children’s outcomes, this evidence points to clear practical ideas which could reap life-long physical and mental health benefits.

Work and stress

Moving into adulthood, chronic stress caused by things such as finding it difficult to get a good job, being in a job we don’t enjoy or being repeatedly unemployed can hamper our body’s ability to dampen down inflammation during a physical illness. Inflammation can be a good thing, helping to promote healing, but if it lingers in the body once its job is done, it can play a role in the onset of heart disease, strokes and cancer.

Our research shows that unemployed people are 40 per cent more likely to have levels of the stress hormone C-reactive protein above the level at which there is a serious risk of heart disease. This finding stayed strong even after considering smoking, drinking and BMI. Another study has shown that middle aged men and women who previously worked in mentally stressful jobs were more likely to exhibit signs of depression later on. This was particularly true for men in jobs with low levels of control, and for women with low levels of social support. Both men and women who had worked in poor quality jobs were considerably more likely to be depressed than their peers with good jobs.

If we are to support people into work and keep them healthy and happy whilst there, this sort of evidence is key to developing workplace and employment policies to help achieve that.

Growing older

It has been reported that one million older people in the UK are suffering chronic loneliness, which has been linked to dementia, high blood pressure and depression, further evidence of the need to understand what will work to help us remain physically and mentally robust into our old age.

Using the UK Household Longitudinal Study, we show that access to a car, mobile phone and computer could prevent older people with poor health from feeling isolated and socially excluded. Making sure that older people in remote communities have access to good broadband with opportunities to develop and improve their computer skills is important. There may also be public health benefits to the development of age-friendly hardware and software, something businesses could support and tap into. Delivering on commitments laid out in the Digital Economy Bill to ‘give every household and business’ the right to ‘an affordable broadband connection, from a designated provider, no matter where they live, up to a reasonable cost threshold’ will certainly be key.

Sweet dreams

We showed earlier the benefits of a good and regular night’s sleep for children, but as we get older, we also appreciate the physical and mental benefits of a restful night.

According to our work, however, while a good night’s sleep may leave mentally healthy people feeling refreshed and ready to tackle the day ahead, it is not necessarily the case for those suffering from depression. The social-biological link to mental health is complex, but we have made great strides in understanding it better, largely thanks to the phenomenal resource that is the British Cohort Studies and other longitudinal surveys. Without these studies and the lifecourse research undertaken using them, we could not say with such authority that tackling stressful events that can happen in early childhood can reduce mental health problems in later life.

Good health, both physical and mental, is something we can build up from before birth right into old age. Bearing that and our evidence in mind, it seems obvious that greater parity in spending on mental and physical health is something of a ‘no brainer’. Some big promises were made in 2016 about a 7 day a week mental health service, increased transparency around mental health service spending, a preventative approach integrated with public health, social care and housing and a government champion for equalities and health inequalities. Acting on those promises sooner rather than later is a must.

Amanda Sacker is Professor of Lifecourse Studies at University College London where she is Director of the International Centre for Lifecourse Studies in Society and Health (ICLS). ICLS isfunded by the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) RES-596-28-0001 (2008 – 2012) ES/J019119/1 (2013 – 2017). For further information and links, see: Never too early, Never too late, free to download booklet, ESRC International Centre for Lifecourse Studies in Society and Health; Life Gets Under Your Skin, free to download booklet, ESRC International Centre for Lifecourse Studies in Society and Health; Child of our Time, ICLS blog on research tracking the health and happiness of children; WorkLife, ICLS blog on research that tracks our working lives and health. Christine Garrington is a freelance writer and consultant.

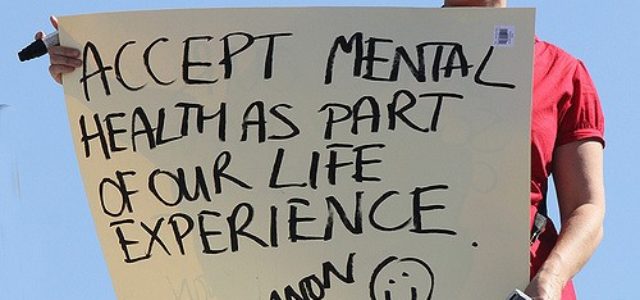

Image by Feggy Art. Mental health on the Fourth Plinth (One and Other) performance art in Trafalgar Square, London. (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)