Katherine Robinson and Monica Krause

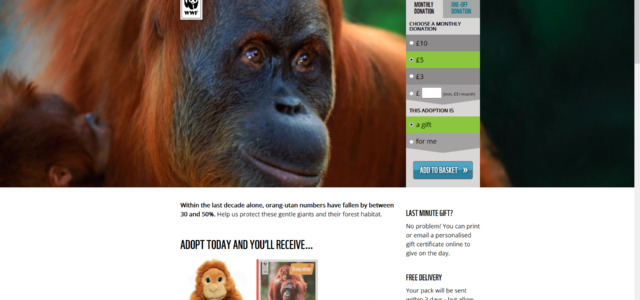

It looks like she’s smiling; her baby is nestled up close to her, and her soft fur is glowing and golden. An appeal states: ‘Within the last decade alone, orang-utan numbers have fallen by between 30 and 50%. Help us protect these gentle giants and their forest habitat’ and asks viewers of the online image to sponsor an animal. Such instantly recognisable images of the charismatic animal are the high-value currency of environmental conservation campaign work.

Conservation organisations have long foregrounded specific species, in some cases to the extent that they provide the organisation’s brand and logo, even while the organisation might actually have a much broader environmental remit. The focus on particular species is sometimes based on scientific arguments about the broader benefits of such an approach – a species might function as an indicator of broader environmental problems when there is not a lot of data available, for example. But it is also acknowledged that there are cultural reasons behind these choices (Feldhamer et al 2002, Kontoleon and Swanson 2003, Tisdell and Nantha 2007).

Charismatic species are what psychologists call ‘schemas’, or ‘prototypes’; iconic examples that serve as a stand-in for the larger category of threatened animals. Charismatic species concentrate a disproportionate amount of attention. As part of our ESRC–funded research project, ‘Triaging Values’, on how international NGOs set priorities, we suggest that schemas of other kinds also shape conservation work. ‘Charismatic landscapes’ stand out among habitats in channelling resources and martialling organisational attention. Furthermore, environmental conservation works within an established repertoire of solutions, which might also be considered charismatic.

As part of the research project we interviewed environmental conservation practitioners in some of the largest international conservation NGOs and zoos about their work. We focus our attention on the practices that shape the ways in which organisational resources – principally time and money – are distributed.

Though some experts have long urged that conservation focus on areas, not species, species continue to shape conservation work. A number of organisations take a single species as their organisational focus: Save the Tiger Fund, Polar Bears International, The Sharks Trust, Save the Rhino, for instance. Zoos are an important funder of international conservation projects and they prefer to focus on species they keep in their collections, partly so they can lend their expertise in animal husbandry and veterinary science. In large NGOs that have gone through systematic scientific processes of priority-setting among geographic areas, these sometimes get complemented or overridden by species-specific programmes.

Furry animals, large predators and birds stand out among threatened animals. Similarly, some landscapes or habitats may be more readily read as threatened and worth saving than others. Since the early 2000s, several international environmental conservation organisations have adopted approaches which divide the world into a series of zones representing places which are both particularly ecologically valuable and vulnerable to loss. Organisational attention and resources are then directed to these areas. The destruction of forests and coral reefs, for example, lend themselves particularly to visual communication. Forest preservation can also be linked to a broader agenda about climate change.

Environmental conservation works within an established repertoire of solutions, which are sometimes adopted relatively independently of whether they are the most appropriate or most effective response. The protection of large areas of land through the creation of national parks and protected areas is one such charismatic solution. This has been the foundational strategy in the history of conservation and for some still constitutes a default response. Monitoring the status of a threatened species or area is another charismatic solution. Conservationists sometimes joke that they are ‘monitoring the environment to death’, suggesting that monitoring efforts are not always clearly linked to survival outcomes. Despite these critiques, monitoring continues to receive new impetus from hopes associated with new technologies and big data. Another charismatic solution comes in the form of projects which connect species and ecological protection with human well-being and economic development, for instance, working with partners to divert local populations into alternative livelihood and income generating projects.

To return to the appeal to help the orang-utan. By sponsoring this individual animal, an issue which is confusing and overwhelming in its interconnectedness – habitat loss, climate change, poaching, globalised patterns of trade and consumption – is translated into a smaller and more manageable scale. We argue that charismatic prefiguring works in a similar way; it enables priorities to be identified and then systematized into actions. Using Erving Goffman’s term, we see how charisma is not only used in ‘front stage’ fundraising efforts, but stretches throughout environmental conservation organisations’ sites of attention, approach to conservation projects and their search for solutions.

Thinking about charisma in this way, as prefiguring particular species, landscapes and solutions, allows us to think about how these are used as organising and framing devices for the complex work of environmental conservation. Charismatic approaches create boundaries; at the same time as some species, landscapes and solutions are prefigured as charismatic, there are others, which are not. Schemas can be considered a coping tool for organisations working in highly complex situations. They help organisations to work out their approaches and to justify their actions, as well as where they decide not to act.

References

Feldhamer, G., Whittaker, J., Monty, A.-M. and Weickert, C. (2002), ‘Charismatic Mammalian Megafauna: Public Empathy and Marketing Strategy’ The Journal of Popular Culture, 36: 160–167.

Kontoleon, A. and Swanson, T. (2003) ‘The Willingness to Pay for Property Rights for the Giant Panda: Can a Charismatic Species Be an Instrument for Nature Conservation?’ Land Economics 79 (4): 483–499.

Tisdell, C. A. and Swarna Nantha, H. (2007) ‘Comparison of funding and demand for the conservation of the charismatic koala with those for the critically endangered wombat Lasiorhinus Krefftii’ Biodiversity and Conservation 16 (4) 1261 – 81

Monika Krause is a Senior Lecturer in Sociology at Goldsmiths, University of London. Her research addresses comparative questions about specialised practices as well as issues in sociological theory. She is the author of The Good Project. Humanitarian Relief NGOs and the Fragmentation of Reason (Chicago University Press 2015), which won the BSA’s 2015 Philip Abrams Memorial Prize for first book in sociology. An edited volume exploring the uses of the concept of field for global analysis (Fielding Transnationalism, with Julian Go) is forthcoming in 2016 as a Sociological Review Monograph. Katherine Robinson is a Lecturer in Sociology at Goldsmiths, University of London. Her research is broadly concerned with questions of urban and public space and organisational life. She has worked on an ethnography of urban multiculture in London and Berlin seen through the institutional context of the public library and is researching prioritisation and resource allocation practices of international NGOs on the ‘Triaging Values’ research project with Monika Krause.