An interview with Susan Derges

Susan, your work speaks to our human continuity with the natural world, which comes across as fragile, delicate and something to be honoured and interfered with as little as possible. If so, how did this dimension of your thought and practice begin and what were the influences upon you?

I think it began when I was painting at Chelsea School of Art in the early 1970’s. There I went to a small extra study session where we were taught how to make musical instruments in bamboo. We had to tap the wood to make it vibrate and saw how dust sprinkled on its surface fell off except for the still points where you could drill or nail without disturbing the resonance of the bamboo. I was intrigued by these still points and started to read up on the physics of sound, discovering Chladni Figures which demonstrate the vibration forms running across resonating glass and metal plates. These beautiful figures arise out of a complex interference of wave forms whereby the peaks cancel out the troughs of wavelets creating non-moving points or areas. Sand placed on the plate’s surface comes to rest in linear forms on these still points. These look so similar to known organic structures that I was motivated to read further about vibrational phenomena and came across the writings of the physicist David Bohm and his book Wholeness and the Implicate Order. Later when I went to live in Japan I came across the same sense of nature being an integral whole and something to be respected – from its very smallest elements to the whole planet – in Shinto and Buddhism. I found that the way these ideas manifested in Japanese culture was very inspiring and suggested to me an approach to art and life that I could work with.

Changing Circumstances addresses the way the world of nature, of which we ourselves form part, is being overturned by human intervention, technology, and so on. How much do these understandings feature in your work?

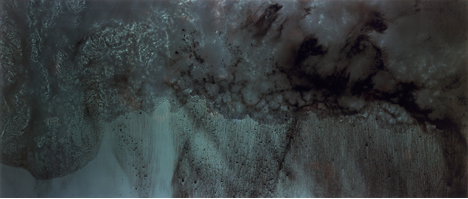

Hugely but not in an overt, conceptual way. When I was living in Japan I became very aware of issues relating to overcrowding, new technologies, loss of biodiversity and pollution and felt deeply affected by the sheer contrast of extreme natural beauty alongside environmental devastation. The traditions of revering the small and the apparently insignificant in the visual arts, poetry and other arts took on a heightened meaning in this modern context. It suggested to me a way to make images through which other people might sense the complexity and sheer importance of our relationship to nature rather than focusing on the negative aspects. In this work I wanted to express a desire to care for and to value what was being lost as well as how really incredible the processes of nature, including our own minds, truly are.

You have worked with university botany and ecology departments. How has this happened and have there been benefits to both sides? And have some of their methods entered into your own?

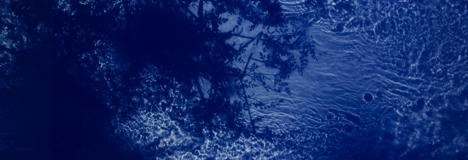

Until recently I worked alone on the development of ideas and methods, appropriating some ideas and experiments from early science books or reading about biology and ecology. I did make a connection with the Marine Biology department of University of Plymouth and this has been very fruitful for me. Their lab technician has collaborated on the current set up I use in my studio and discussions with the staff there have been mutually very interesting. We have all been surprised about the degree of crossover in our working methods, particularly the need to combine working outdoors in the landscape with modelling the same subjects in the lab or studio in order to understand both the complexity and particularity of subjects like rock pools and intertidal environments. In the early ’90’s I made a time lapse video of a frog egg going through cell division from single cell to frog and they were surprised that had been possible at that time as no one in their field had managed to record the process in such detail. They had filmed a jelly fish going through the same stages of early development and that was interesting for both of us. I learnt a lot about the management of artificial marine environments from the lab technician at Plymouth but would say the benefit has probably been more on my side in terms of the immediate usefulness of our interactions.

Some of your work takes the form of experiments, in some respects harking back to the early days of photography. How do you locate yourself in the photographic tradition? Is your use of lens-less photography a harking back or an attempt to establish a new relationship with the objects of your perception?

When I began making camera-less images, it was as a means to an end – how to record Chladni figures directly onto photographic paper. I wasn’t making a reference to early photography at that point. It was only later, after making those initial prints that I came across Fox Talbot and Anna Aitkins, who have remained a reference up to the current Tide Pool work. In terms of where I would see myself within the photographic tradition it would be more in relation to constructivism and that period of looking beyond the visible into what might lie beyond our perceptual world and that interest in both science and imagination. My early work as a painter was in the area of constructivism and it seems to remain relevant. That said, I’m interested in how one can make images in this current context rather than looking back to how things were approached from such a different era.

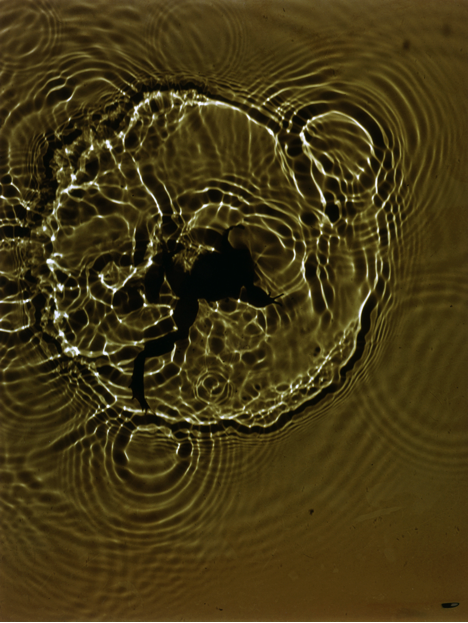

I think the most important factor in how I approach the medium of photography is how to make a close contact with something or even how to immerse oneself, visually, in an element like water, a river or an ocean, or enter into its state, through taking unfamiliar positions such as being in or underneath the water or looking at something seen through a lens-like droplet. Usually my way of making this work is connected to a central metaphor, such as a state of immersion in the case of the River Taw series and the decision to immerse the paper beneath the river’s surface and expose to light in order to make a direct contact print of all the vortices and wave forms in its movement.

All symbolism has a social dimension, for example in the form of object- sign – interpretant formula. On the other hand, the power of artwork is that it can impart many different meanings and one can revisit it again and again for new meanings. If there is one overall meaning you wish to impart to the viewer, what would it be?

It’s hard to translate the image making process into words, especially a single message, as the work is intended to operate in a multilayered way where the impossibility of one absolute version of reality is part of the ‘message’. But if I look back over the past 35 years of making I can see that my preoccupation has been the desire to find, visualise and communicate how interrelated the self is to that which is considered to be other, whether that other be nature, another person or even the mystery that lies behind our experience of life on this planet.

Susan Derges was interviewed by Geof Rayner

Susan Derges is a British-born photographic artist specialising in camera-less photographic processes, most often working with natural landscapes. She studied painting at the Chelsea College of Art and Design and at the Slade School of Art. Derges has works in several public museum collections including the Metropolitan Museum, New York, the Art Institute of Chicago and the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. She is represented by Danziger Gallery New York,[4] Purdy Hicks Gallery (London),Ingleby Gallery (Scotland) and Nichido Contemporary Art (Tokyo, Japan). In 2014, Derges was awarded an Honorary Fellowship of The Royal Photographic Society. Publications of her work include “Liquid Form”, Michael Hue Williams, London 1995, “Woman Thinking River”, Fraenkel Gallery, San Fransisco , 1998, and “Elemental” , Steidl Germany 2010.

Header Image: River Bovey