Geof Rayner

Two international photography events this year reveal the investigative promise of photography. Rencontres d’Arles, from July to 25 September, is a yearly celebration of photography in its widest possible forms. The Fotofest Biennial, in March/April 2016 in Houston, presented a tighter thematic focus attracting 275,000 people from 43 countries. Changing Circumstances: Looking at the Future of the Planet, attached an appealing, non-frightening title to its underlying focus on the Anthropocene, the recent scientific term for our current phase of human-managed (or mismanaged) planetary ecology. The exhibition, together with an accompanying book, dealt with an array of social-ecological issues: industrialisation and urbanisation; bio-diversity; water; the use of natural and human resources; human migration; global capital, commerce and consumption; energy production; and waste.

Geof Rayner attended both events and contributed the essay ‘Surviving the Anthropocene’ to the Changing Circumstances book. He has ‘curated’ this special issue of Discover Society and, in this essay, he considers the social role of photography in the context of the Arles festival. In discussing the theme of Fotofest he also introduces the work of eleven photographers/artists featured in this issue of Discover Society, all of whom attended Fotofest and most of whom exhibited there. In conclusion, he argues that photography is well placed to communicate ideas, information and feelings on matters where other disciplines, including the natural and social sciences, usually struggle.

**

The beautiful Roman-era French city of Arles is the location of Rencontres d’Arles, the world’s oldest international photography festival (est. 1970). According to Sam Stourdzé, the director, “Photographers are investigators. They know their subjects like the backs of their hands. When they go out on the field, they meet, interact and explore.” Photography has the allure of social science, with the exception that photographers communicate (mostly) through images. As if to underline this fact throughout the festival, a tricycle rickshaw, its rider scouting for customers, trundled through its narrow backstreets. Displayed on the back of the vehicle were the words of the late Andy Warhol: “I never read. I just look at pictures.”

The famously monosyllabic artist seemed to be suggesting here that the image had overtaken the word, at least for him. Warhol also defined art as “what you can get away with”, and thus it might be easy to reject his comments as superficial and banal. This view would be mistaken. More than ever we live in a world of images, or to use CS Peirce’s semiotic vocabulary, a world of signs, with visual signs at least as powerful as words. Warhol’s own artwork, a melange of photography, screen printing, iconic portraiture and bold use of colour, might be pigeonholed as just ‘art’, but it is also a reflection of the culture of the USA, the country of Warhol’s birth. To even briefly examine his artwork is to see the connection between the political and cultural ambitions of the USA and an art form which reflects the society’s commitment to consumer capitalism. And thus it is possible to make a link between a bicycle rickshaw in Arles, the nature of photography-based art and an exhibition on nature thousands of miles away in Houston, Texas.

Warhol’s artwork developed in the conditions of post-World War II USA. With Europe in ruins, it eagerly slotted into position as the scientific and industrial leader of the world. France’s pre-war status in the visual arts was broken and the locus of modern art moved 3,000 miles west (helped by the CIA and the US art establishment ‘s deep pockets). American mass culture asserted hegemony via Hollywood and TV, but arguably its most significant achievement was its consumer products industry. With this in mind, Walter Rostow’s (1960) ‘Stages of Growth’ thesis declared that the USA had achieved “the age of high mass consumption.”[1] The USA offered itself as exemplar to the developing world and Rostow – foreign policy advisor to two presidents – argued that the desire for mass affluence was the bulwark against the miseries of communism (denoted by Russia’s empty shops and joyless consumer choices). The psychologist George Katona confirmed that the newly affluent society meant that former luxuries such as homeownership, durable goods, travel, recreation, and entertainment were “no longer restricted to a few”.[2]

Although apolitical, often decried by the left, and more a voyeur than natural critic, Warhol’s art placed him among the objectors. On the few occasions when journalists coaxed a comment, Warhol said that he thought that commercial things ‘stink’ and that “as soon as it becomes commercial for a mass market it really stinks.”[3] For Warhol celebrity glamour – identified as applying equally to baked beans as to movie stars – blended falsehood and desire so successfully that it was impossible to know “where the artificial stops and the real starts”. Given that everything was fake (although no less interesting for being so) it wasn’t surprising, he declared, when you see the famous person in the flesh, “the whole illusion is gone.”

Warhol was a closet environmentalist. Having land and “not ruining it”, he said, was “the most beautiful art that anybody could ever want to own.” His nature screenprints were exhibited at the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson Hole, Wyoming in 2013. These present an array of endangered species, including rhinos, lions, primates and butterflies.

Commercial photography today remains in thrall to the business of selling, be it of reputations, bodies or brands. With an apparently endless public appetite for celebrity photos and gossip, the MailOnline is the most visited English-language newspaper website in the world, with over 11.34m visitors daily (August 2014) and with 70% of its traffic from outside the UK. In contrast, most photography is actually amateur. The Brownie camera, introduced in 1900 and regularly updated, was sold in its thousands until the late 1960s. Combined with inexpensive Kodak film, it provided the basis for the family photo album. In contrast, ownership of more sophisticated cameras was rare, at least until the 1970s. The situation is incomparably different today. The cameras on inexpensive smartphones can rival many cameras. There are several important differences from the past, but what is most eyecatching is the pervasiveness of these new devices. In the words of OFCOM, the UK media regulator, Britain is now a ‘smartphone society’ with fully 90% of 16-24 year olds owning one. [4] By 2014-5, according to the same study, an estimated 1.2 billion ‘selfies’ were snapped by nearly one- third of UK adults. With the cost of imaging falling towards zero (hence the demise of Eastman Kodak) the smartphone’s easy-to-use picture taking, rapid image transmissibility, and linking to ‘community’ on-line display, might soon render paper-based family albums obsolete – at least for younger generation. It is already forming the basis for a new type of ‘instant news’ as direct-to -the -web images are taken, video and still, of incidents ranging from police beatings to terrorist bombings.

As equipment has fallen in price, photography has now become a low cost entry point to the creative arts, with street photography, landscape and nature photography leading the way. Photography may be a wonderful amateur pastime, but professional photographers need to earn a living. Given the decline in the fortunes of newspaper publishing, life is getting more difficult. Photography, even the more artful side, remains a business, and it is a tough one. As the thoughtful economist Deirdre McCloskey has observed, “Sneering at commerce from the heights of the aristocracy or the depths of the peasantry is … ancient and usual.” This observation makes what is achieved and presented at festivals like Arles all the more striking. Photographers make art, and often great art, despite the fact that it is difficult to earn a living from it and difficult to get work shown. Making the work or investigating the background issues takes time, thought and dedication, and with some projects it takes many years. The technology-driven image of the camera, not the photographer, doing ‘the work’ is entirely false.

At Arles, Irish photographer Eamonn Doyle integrated street photos taken near his home with sound and drawings. His pictures reveal a city of increasing diversity, a radical contrast with the Dublin of James Joyce. The strength of Arles – recognising that it was the French who were photography’s first practitioners – is also that it exposes visitors not only to younger photographers but also to great photographers of the recent past along with the distant past. Don McCullin (b. 1935) photographed conflicts in Vietnam, Cyprus, Beirut and Biafra in ways which may have influenced their outcome. He also documented British post-war poverty and homelessness in a series of stunning images which capture people, context and culture, often in just a single image. This was a type of investigative photography first undertaken by Jacob Riis (1849 – 1914) in New York City more than century ago. Like McCullin, the Danish-born Riis brought in his own experience of hard living to the understanding of people in poverty. His work too was shown at Arles.

Photography is a pluralistic field, and while photography is a profession, and thus operates with business ethics, its broader purposes can also burst through these limitations. Whether the photograph is an art form – a debate since its inception – is irrelevant. Successful photographic imagery has, like any other art form, the power to stand the test of time and it can also tell us what time actually feels like.

Wendy Watriss and Fred Baldwin, the originators of the Fotofrest, and Steven Evans, the new Director, asked photographers to contribute to one theme, planetary health. In so doing they embraced ecological perspectives which were implicitly in direct opposition to the 1950s growth-optimism of Walter Rostow (who by chance Watriss and Baldwin had previously met) and, for that matter, mainstream economics since. According to Evans, the Anthropocene not only comes with “overwhelming evidence” of a fraying global ecological system but of science’s uncomfortable dual role in regard to it: one of analysing and exposing societal risks but also, more negatively of “inadvertently (producing) new risks through its generation of new discoveries and new technologies.” Was there an economic alternative? The need for one was certainly implied both in the festival and publication. If one existed at the time of Stages of Growth, probably the nearest thing to an alternative was that of US-domiciled British economist Kenneth Boulding (1910-1993). He had argued in 1964 that the drive for ‘mere accumulation’ only led to the “piling up of things.” [5] Two years later he went further: “The essential measure of the success of the economy is not production and consumption at all, but the nature, extent, quality, and complexity of the total capital stock, including in this the state of the human bodies and minds included in the system.”[6] In contrast to an expanding world frontier of mass consumption, the appropriate image was the Earth as “a single spaceship, without unlimited reservoirs of anything, either for extraction or for pollution, and in which, therefore, man must find his place in a cyclical ecological system.” If Boulding’s ideas attracted public attention (he was even elected President of the American Economic Association in 1968), his theoretical shortcomings were evident in this quotation, one which supports the neoliberal notion that bodies and minds represent ‘capital assets’.[7]

In any case, a half-century on, it’s clear which route was followed. Even communist China embraces the consumer growth economy, in fact outdoing the USA. Ecological literature refers to the last two centuries as the period of ‘the great acceleration’ and certainly since the 1950s, economic growth went into hyperdrive. The positive consequences are many: life has become easier as the technologies of existence have improved. And consumerism has brought many benefits too, albeit with wide disparities. While in the west, a sense of deprivation might be the use of an old model of mobile phone; in the poor world, in contrast, people often lack cheap, efficient wood stoves to replace dangerous and pollutant open fires. In ecological aspect, the consequences of consumer affluence in the West and its emulation in the developing world is telling right across the planet as growth economics, which drives the need for base commodities for production, strips out forests, pollutes water tables and throws CO2 into the air. As the debate on climate science has shown it’s difficult to portray these trends and their severity in ways which either makes sense to people or which produces an emotional impact. The Global Footprint Network, a partnership of seventy environmental organisations, tries to so by employing a simple, evocative measure of how much biologically productive land and water are required by individuals or households to produce all the resources consumed in economic activity and to absorb all the waste generated. In 1970, they suggested, the planet was roughly in balance between consumption/waste and ecological resources. By 2007, 1.6 planet’s worth of ecological resources was required.

This type of mismatch was first pointed out in systematic terms by Club of Rome’s Limits to Growth report in 1972,(7) but it was another two decades before this message was translated into global action, which came eventually at the Rio Summit of 1992 (formally known as the UN Conference on Environment and Development.) Rio led to Local Agenda 21, as agreed by 178 heads of state. What difference did Rio make? After decades of effort to shift economic development towards sustainability goals a 2012 review of Agenda 21 observed that over the previous twenty-five years resource use had diminished by 30 percent per unit of global economic output. Far less positively, however, 50 percent or more natural resources were now being consumed. [8] In the last decade, global business, rather than minimising the threat of ecological damage, has showed greater concern. The annual Davos-based Global Risks surveys indicates that a growing number of business leaders appreciate the risks of failing to act. [9] Overall however, economic growth remains the principal indicator of a society’s success. Spaceship Earth, is, in effect, set on a collision course with its own operating manual. The need to communicate this the public, and seek alternatives ways of living, is therefore paramount.

The term Anthropocene (derived from Greek Anthropos = human and cene = new) draws from this context. In essence the central idea is that humans have become the dominant influence over the life of the planet. In this circumstance, there are new risks, many which – like climate change – require urgent action. Unsurprisingly, the notion is opposed (in fact ignored) by neoliberal growth economists. Nevertheless, others supporting environmental action and therefore who might be otherwise sympathetic have also taken issue with the concept. For some of these, it was an error to present the concept in terms of geological periodisation. Others have raised questions about start dates, pace, spread or severity. Social scientists have adopted a questioning stance too, saying that it says too little about social causation or social consequences. These points are certainly matters for debate and elucidation. In terms of the social science critique, however, it might be read in terms of 20th century attempts to distance itself from early accusations of ‘biologism’ and from natural science and environmental matters more generally. For all that, what the concept does achieve is to gather all multifarious strands of concern about planetary health under one heading, although whether the term will gain ‘traction’ in the future remains to be seen.

An exhibition mounted around such a difficult or controversial concept might seem daunting. In fact, the concept itself may be new, but the photography of ecological impact is not. Nature has been a topic of photography since there was photography. Nature photographers have often been in the forefront of those calling for nature protection. Demand for nature images is huge, reflecting in part large memberships of environmentally-focused organisations (in the UK, RSPB has over 1 million members while the Wildlife Trusts have over 800,000). BBC nature programmes achieve world-wide acclaim while the (US) National Geographic magazine (now owned by News Corporation) achieves a world-wide audience. That said, nature photography is often artistically conventional. That which was shown at Fotofest was nevertheless masterful, in particular the work of David Doubilet, Joel Sartore, and David Littschwager.

In investigating a complex topic like the Anthropocene it is plain that many different approaches and topic areas were warranted.

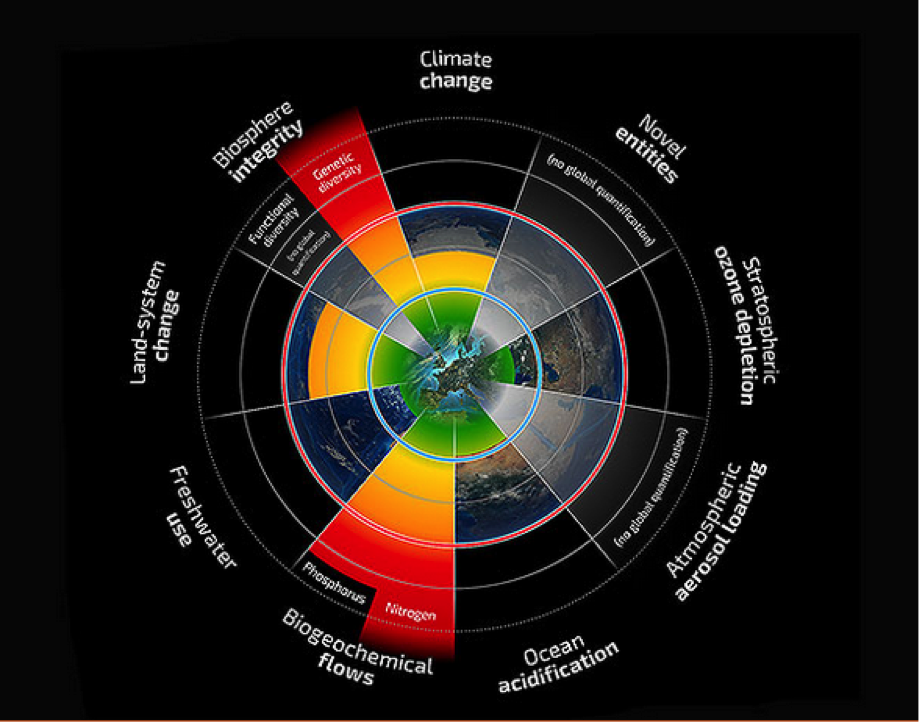

The exhibition, as with Arles some months later, showed a huge plurality of approaches. These included, for example, the more abstract, information-focused, or three-dimensional and sculptural forms, and constructed imagery. Some photographers explored the social nature of the Anthropocene, taking up economic growth and its consequences. Could any one of these approaches express a difficult concept like the anthropocene? Probably not, since a full understanding requires many images. A diagram from the Stockholm Resilience Centre (and reproduced in the Changing Circumstances publication) attempts present a global picture of the risk to ecological boundaries across critical areas for planetary health. But even this diagram requires considerable supporting information for its interpretation; it too is scientifically controversial.

What the photographers showing work at Houston achieved was the creation of memorable images, some of which address sense of place, concretise feelings about the human experience of nature (or the risks to nature), or address many other topics that the curators requested. To return to Warhol’s observation about pictures, people do look at photographs; but, against Warhol, they may then begin to read, to adjust their own behaviours and even to participate in social movements.

For a festival addressing climate change, it was especially poignant that work was displayed in oil industry office lobbies. In fact, this was understandably so, Houston being the world’s premiere energy industry city. The city is bordered by a massive hinterland of energy extraction. This image, taken from 35,000 feet above West Texas (and shown briefly at the auditorium of the Houston Museum of Fine Arts) reveals a landscape pockmarked by thousands of fracking pads stretching to the horizon. To put this image in context, there are some 291, 996 wells/fracking pads in Texas (2015 data).

Eleven photographers were approached for Discover Society because their work dealt with the topics in novel and interesting ways and because of the sheer quality of their vision. American artist Amy Balkin’s Atmosphere posters bring together image and text, in the format of a Cloud Code Chart. The information she presents is thorough and full. It presents the science but also asks questions. The viewer is forced to work. Similarly information-based German artist Ingo Günther’s Worldprocessor uses the globe as motif. Each individual globe – and he has made 300 so far – addresses a particular theme and draws on information the artist has acquired from organisations such as UNO, the OECD, Greenpeace, journalistic archives, statistical annals or from internet data banks. In Houston, a room was filled with such globes.

Mandy Barker, a British artist, also uses a research-based method in her constructed images. She focuses on one substance only: plastic. For the SOUP series she asked people from around the world to send her plastic debris. Her series PENALTY uses the same approach but additionally aimed to create awareness of marine pollution by focusing attention on the football as a single plastic object and global symbol that could reach an international audience. The result is both enjoyable yet disturbing and of course communicates through a world-wide idiom, football. Barbara Ciurej and Lindsay Lochman also employ constructed images, but do so from the perspective of the new technology of processed food ingredients. In interpreting the myth of the American landscape and the US notion of ‘Manifest Destiny’, they examine the new frontier of processed food, with its links to industrialised farming and consequences in mass obesity.

Brazilian photographer Pedro David’s work examines the survivability of ‘native nature’ against the imposition of clone woodlands. Eucalyptus trees, introduced for their rapid growth, are today used by the Brazilian iron and steel industry. As with Mandy Barker, the art work has the explicit purpose of dramatising the consequences of an (almost) biodiversity free woodland thereby revealing how the landscape is being transformed, usually without public debate. His photographs appear to work at the level of ‘feeling’, producing a profound emotional responses.

British photographer Gina Glover’s Park project is located at the famous Joshua Tree National Park in south California, not shown at Houston. It juxtaposes the two purposes for US national parks, one being the preservation of nature and education about nature, the other being access to semi-wild areas for camping, hiking and climbing as well as general sight-seeing. For many people, the park is one entered and seen from the windows of a motor car. It’s a place where people bring their camper vans and picnic hampers to experience Nature’s Disneyland. The title reflects this another meaning to park (ie vehicles). Her work also exposes the viewer to two conventions in photography, one being the art photograph of the landscape, and shown without human presence, and the other the documentary signs of human presence.

Another British photographer, Susan Derges, attempts to ‘enter nature’; in effect to let nature and natural processes speak through her images. In presenting her work Derges is interviewed about how her ideas and art practice developed, along with her photographic techniques. What she provides is an immensely rich account of the development visual ideas, some connected to other senses, like sound, and others to non-western traditions of art. The overall impression is of one of delicate patterns of nature carried forward into the equally delicate qualities of art.

Slovenian photographer Matjaz Krivic’s project on gold mining in Africa, also not shown at Houston, observes that gold is essential to mobile phones and upon which our talkative and selfie-photographed world now depends. Mobile phones, he shows, represent the high-tech end of a supply chain of highly dangerous unregulated mining alongside the regulated. His exploration of artisanal gold mining takes us Burkina Faso, formerly known as Upper Volta, which is one of the poorest countries in the world, ranking 183rd out of 187 countries on the UN’s Human Development Index.

German-American Robert Harding Pitman’s theme is urbanisation and architectural diversity. He examines the speculative building industry, which takes advantage of energy abundance and the motor car to spread urbanisation to places which otherwise would not be ecologically feasible. As he observes, the trend began in the deserts of California in the 1950s, but then spread elsewhere. Speculative building, he notes, has the purpose of producing rapid profits, but such ventures often contradict the phases of the business cycle. Both in Spain and the USA, the building boom helped lead to the global financial crisis of 2008.

Lastly, Brad Temkin is a photographer from Chicago, USA, who describes himself as an optimist, which is perhaps why his Roof Tops project is here left to last. Temkin’s positive view is that cities can meet the challenge of sustainability and, with urbanisation proceding at such a rapid rate, they are being forced to. In Chicago, although a trend fast developing in other major cities of the world, buildings are developing roof top gardens, just as at street level empty patches of land are sprouting community gardens. It’s a positive development, as much as for the enthusiasm and new sensibilities it generates as for the gardens created. Brad Temkin must be right, for however difficult or boxed people feel in the fraying human-ecology circumstances of the early 21st century the critical issue is to find new, positive responses to new (and old) problems.

What both Arles and Fotofest show is that art photography can engage with difficult issues, and often far better than other fields or disciplines which give no consideration to aesthetic or emotional impact. It’s not a case of art and photography vying for public recognition, that is already there. What’s needed perhaps is breaking up a compartmentalisation of outlook, as was exposed to the curators when the publishers tried to distribute the Changing Circumstances publication. Art sources rejected an environmental publication; environmental sources rejected the tag of art. This, too, appears as something to challenge.

Notes:

1. Rostow, W.W., Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto. 1971, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

2. Katona, G., The Mass Consumption Society. 1964, New York: McGraw-Hill.

3. O’Sullivan Shorr, C., Welcome to the Silver Factory: The Birth of the Pop Art Era. 2015, New York: Open Road Media.

4. OFCOM, The Communications Market Report. 2015, OFCOM: London.

5. Boulding, K.E., The Meaning of the Twentieth Century: The Great Transition. 1964: George Allen & Unwin.

6. Boulding, K., E, The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth, in Environmental Quality in a Growing Economy, H. Jarrett, Editor. 1966, Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore,MD. p. 3-14.

7. Spash, C., The Ecological Economics of Boulding’s Spaceship Earth. 2013, Institut für Regional- und Umweltwirtschaft: Vienna.

8. Dodds, F., K. Schneeberger, and F. Ullah, Review of implementation of Agenda 21 and the Rio Principles 2012, New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Division for Sustainable Development.

9. World Economic Forum, Global Risks report 2015. 10th edition. 2015, World Economic Forum: Geneva.

Geof Rayner has taught at universities in the USA and UK but chiefly works as freelance consultant for international organisations such as WHO and the European Commission. He was a founder and chair of Photofusion, London’s largest independent photography centre, and formerly chair of the UK Public Health Association. His recent books include Ecological Public Health: Reshaping the Conditions for Good Health, with Tim Lang, Routledge, 2012 and The Metabolic Landscape; Perception, Practice and the Energy Transition, 2014, with Gina Glover and Jessica Rayner, published by Black Dog. Changing Circumstances: Looking at the Future of the Planet, is edited by Wendy Watriss and Steven Evans. It is published by Schilt Publishing, Amsterdam and available from real and online bookshops.

Header Image: Geof Rayner