Kasia Narkowicz

Assaults on Roma homes, burning an effigy of an Orthodox Jew in a public demonstration and the desecration of century-old mosques are some of the recent examples of racist violence spreading across Poland. The anti-racist organisation Nigdy Więcej [Never Again] says that Poland is currently witnessing the ‘biggest wave of hatred’ in the country’s recent history.

While nationalist groups are responsible for the more spectacular expressions of hate, the problem is wider and more deeply seated. Racism bursts out in online forums of secular liberals as well as from Church lecterns across the country. The newly elected Prawo i Sprawiedliwość [Law and Justice] party is making matters worse. Most recently it abolished the only government body combatting racial discrimination, because it deemed it pointless, sending a symbolic message to the country’s already fragile minorities.

Gazing Eastward

The part of Europe that begins somewhere east of Germany and continues around the bend of the Black Sea is either ignored in Western media, or homogenized into an indistinguishable mass of babushka-like figures sitting, apparently since the Communist days, on horse and cart, slowly progressing towards the high road of modernity. When Central and Eastern Europe does appear on the Western radar, as it has in the context of the ‘refugee crisis’, hasty assumptions explain the racial violence mainly as predicted outcomes of the region’s ‘bad refugee politics’ and right-wing conservative Catholic government rule. It seems as being predominantly Catholic automatically explains the country’s racism.

It is true that the 2015 elections of the conservative party gave legitimacy to right-wing nationalists in their quest towards ‘de-Europeanisation’ and ‘re-Christianisation’ of Poland. Yet the current events are part of a longer trajectory of racist expressions in the country by a wider range of groups. Racism in the public debate, particularly targeting Muslims, was already rife during the 2010 first Polish mosque controversy.

When I conducted fieldwork in Poland 2011-2012 as part of my doctoral research on the mobilisations against two purpose-built mosques in Warsaw, it was not the far-right groups who were the main orchestrators of the opposition but the liberal group Europa Przyszłości [Europe of the Future]. Their first prominent public demonstration in 2010 against the construction of Warsaw’s first purpose-built mosque saw an alliance of anti-Muslim activists from abroad, pro-Israeli supporters as well as far-right nationalists. The protests did not stop the mosque opening, yet it gave rise to a wave of attacks on the few mosques scattered across Poland. The mosque in Gdańsk was set on fire, Poznań mosque was plastered with Islamophobic slogans while the Imam received death threats and a pig was sprayed on the wall of the traditional Tatar mosque in Kruszyniany.

The old Tatar mosques remember the once multicultural Poland, home to proportionally the largest Jewish population in Europe and a large Muslim minority. History has radically changed the Polish landscape, making it one of the most homogeneous countries in Europe. In the country’s long Islamic presence, this is the first time that the traditional mosques and their adjacent cemeteries have been vandalised, where mosque construction has been successfully petitioned against and where people looking visibly Muslim have been attacked.

Who is targeted?

While all racialised groups are facing hostility, the attention is directed towards Islam and Muslims who are constructed as the country’s prime ‘threat’. The Catholic right finds that their mission of re-Christianisation of Europe is interrupted with the (symbolically) incoming Muslim migrants and the secular liberals argues that their European values are now threatened by ‘radicalism’.

But on the streets, any person of colour is the target. Organized demonstrations targeting ethnic minorities are often mobilised online. The anti-migrant online presence such as NIE Dla uchodźców w Polsce [NO to refugees in Poland] merges with Islamophobic camps that came to prominence in the wake of the 2010 Warsaw mosque controversy. Nie dla Islamizacji Europy [No to Islamisation of Europe] started in 2012 and currently has over 290 000 likes. Many cities across Poland have ‘No to Migrants’ Facebook pages from where the offline protests often are organised. When a recent far-right nationalist march was taking place in Białystok, foreign students of the local university were urged on Facebook to stay inside ‘to avoid any unpleasant incidents’. Such incidents have included a Pakistani man recently being beaten unconscious and a black woman being called the Polish equivalent of the ‘N-word’ and slapped in the face. There are also more everyday racist acts such as facing pressure at work to remove one’s hijab.

While public expressions of racism, and particularly Islamophobia, have become more publicly acceptable and witnessed a particularly radical surge in 2015, these nevertheless need to be understood in the country’s very specific history of Othering.

Polish racism

In a 2011 European survey, almost half of Poles were of the opinion that there are ‘too many Muslims’ in their country. Despite an estimated number of only 35 thousand Muslims in a country of 38 million people, the much debated threat of the ‘Islamicisation of Poland’ is not dissimilar to the still echoing discourse of a ‘Jewish take-over’ where the Jewish community in Poland represented even smaller numbers.

While racism and Islamophobia in countries such as UK should be analysed within a wider framework of the country’s colonial past, in Poland, understanding racial discrimination of today needs to go hand in hand with the country’s history of anti-Semitism – one that Poles themselves still speak about with unease. In the Polish collective memory and echoed in films such as ‘In Darkness’, Poles are represented as heroes who largely helped Jews during the Second World War rather than those who also participated in their oppression. This image is so strong that recent films challenging this narrative such as ‘Pokłosie’ [Aftermath] telling the story of the Jedwabne massacre gave rise to a national debate and was condemned by some right-wing commentators as ‘manipulating history’.

According to recent statistics Jews are more liked and accepted than two decades ago. Replacing them as the least liked group are the Muslims. National surveys in the last decade have shown a consistent level of prejudiced particularly towards the Roma and Arabs.

The government’s response

The newly elected Polish conservative government does the opposite of combatting hate filled public discourse.

The Polish prime minister’s tempered enthusiasm towards accepting refugees, preferably only those who are Christian, signified the anti-Muslim prejudice at the heart of the ‘refugee crisis’. A newspaper closely linked to the ruling party ran a cover portraying a white woman draped in an EU flag that was torn apart by brown male hands, signifying a muddled defence of both (or either) nationalistic and EUropean values, symbolised by the women’s body as the reproducer of the core values (whatever they might be).

Most recently, in May 2016, the PiS party abandoned the only government body committed to tackling racial discrimination. The Council Against Racial Discrimination and Xenophobia was established in 2013 by the former Prime Minister and current President of the European Council Donald Tusk and included representatives of the main government departments. This work will now be absorbed by the Advisor on Civil Society and Equal Treatment.

Amongst increased racialised violence taking place in the country, the Polish government is sending a discouraging message: that it is willingly neglecting the worsening situation of its ethnic and racial minorities and paving the way for waves of hatred to crash onto an already divided Polish landscape.

Kasia Narkowicz is Research Associate at the University of York and researcher at Sodertorn University. She works on Islamophobia and racism in Poland and the UK.

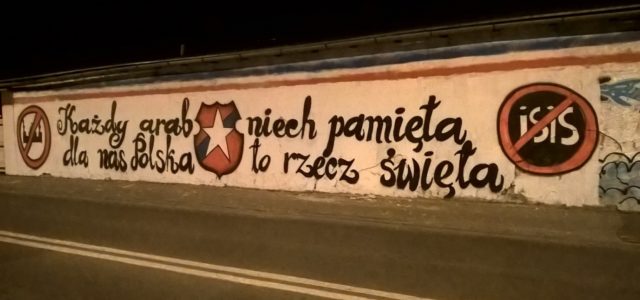

Image: Konrad Pędziwiatr ‘Every Arab should know that Poland is holy to us’.