Carol J. Adams

In 1968, at the famous feminist protest against the Miss America Contest, two posters were held up next to each other. The first was a photo of a woman’s backside, shown cut up like a piece of meat, labeled “rump,” “round,” “loin,” “rib,” etc. Next to the woman on that first poster and reinforcing the misogyny of the image were the words “Break the Dull Steak Habit.” “Welcome to the Miss America Cattle Auction,” announced the other poster. While feminists were saying, “We aren’t that,” they were also acknowledging, “You are treating us like that.” The protest “women are being treated like animals” suggests the intuition, “women and animals are treated in similar ways in a patriarchal culture.”

In the early 1970s, the implicit statement that “there is some sort of connection between the treatment of women and animals”, became explicit with the appearance of ecofeminism. In our recent ecofeminist anthology, Lori Gruen and I explain that “Ecofeminism addresses the various ways that sexism, heteronormativity, racism, colonialism, and ableism are informed by and support speciesism and how analyzing the ways these forces intersect can produce less violent, more just practices.”

I first heard the term “ecofeminism” in 1974. I was taking a class on feminist ethics with the philosopher Mary Daly and she had just arrived from France where she had picked up Françoise d’Eaubonne’s book Le féminisme ou la mort. Daly translated parts of it and read them to us in class.

During that time, while living in Cambridge, Massachusetts, I realized there was a connection between feminism and vegetarianism. Over the next two years (1974-1976), I interviewed more than forty feminists who were also vegetarians about their reasons for becoming vegetarian. Many of them articulated an ecofeminist perspective that located animals within their analysis. One said, “Animals and the earth and women have all been objectified and treated in the same way.” Another explained that she was “beginning to bond with the earth as a sister and with animals as subjects not be objectified.” A third reported, “Feminists realize what it’s like to be exploited. Women as sex objects, animals as food. Women turned into patriarchal mothers, cows turned into milk machines. It’s the same thing.” I discuss these responses in my essay “Ecofeminism and the Eating of Animals” found in Neither Man nor Beast.

My first essay arguing that a feminist perspective offers insights into the treatment of animals and that patriarchal culture legitimates meat eating appeared in 1975 in an anthology called The Lesbian Reader. I was not the only one writing about these issues. In 1974, Connie Salamone travelled around the United States and to Europe, advocating for the inclusion of interspecies solidarity in emerging feminist manifestoes. Around the same time, Andrée Collard began working on a book that was published, in 1988: Rape of the Wild: Man’s Violence against Animals and the Earth. It focused on animal experimentation and hunting.

When, in 1976 Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation appeared, feminist activism and theory had begun to identify interconnected oppressions. Singer, although probably not consciously, set this understanding of interconnected oppressions back with his prefatory statement, “There’s been Black Liberation, Gay Liberation, Women’s Liberation. Now let’s talk about Animal Liberation.” It seemed to position Animal Liberation as the teleological fulfillment of those earlier activisms: “Well Black Liberation, Gay Liberation, Women’s Liberation–that’s been done, now it’s time to focus on animals.” As people joined the animal liberation or animal rights movement (Tom Regan’s philosophical work, The Case for Animal Rights, appeared in the early 1980s), they offered an image of who they were not: “We’re no longer little old ladies in tennis shoes.” See my piece on this claim.

By the early 1980s, as more and more animal advocacy groups emerged, though they were rhetorically attuned to sexism and racism, inclusiveness was elusive. The visible spokespeople, theoreticians, and writers were overwhelmingly white and male. In the United States, in response to this and the understanding that feminism is a transformative philosophy that embraces the amelioration of life on earth for all life-forms, Feminists for Animal Rights started in the United States, as well as World Women for Animal Rights, founded by Connie Salamone, the Canadian Feminists for Animal Welfare, the Australian Feminists for Animal Rights, and the British Women’s Ecology Group, which had a special emphasis on “understanding the present human predicament and mass animal suffering (vivisection and factory farming, etc.)” from the perspective of the “systematic crushing of the Feminine Principle by patriarchal power.”

The difference between the 1968 protest and contemporary feminism is not that we now know what happens to animals. How animals live and die through industrial farming has been known since 1964, with the publication of Ruth Harrison’s Animal Machines. Her book could have joined Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in shaping the perspective of environmental activists to include industrial agriculture. Sadly, it did not.

The difference between 1968 and now is not that we now understand the environmental impact of eating animal products. That has been known for forty years, though more and more voices have been added.

The difference between 1968 and now is that forty years of feminist thinking about, and responding to, intersectional oppression has created robust theory and activism. In our 1995 anthology Women and Animals: Feminist Theoretical Explorations, Josephine Donovan and I argue that “theorizing about animals is inevitable for feminism.” To elaborate: Feminism inherently contains within it a critique not only of sexism but of speciesism. When we look to the other side of the species line we can see that certain misogynist practices and attitudes have fled across it or arisen from it. Eating animals and dairy participates in a patriarchal ethics of objectification. A feminist ethics of care offers engagement with those who suffer.

I understand many impediments exist to recognizing and acting on these insights: the celebration of male authors as “fathers” in the animal movement (Singer and Regan); the disowning of that perennial activist – the little lady old in sneakers; the misogyny of PETA’s advertisements, the lack of media attention to grassroots activism led by women that is intersectional (for instance, Food Empowerment Project, Brighter Green, and A Well-Fed World.

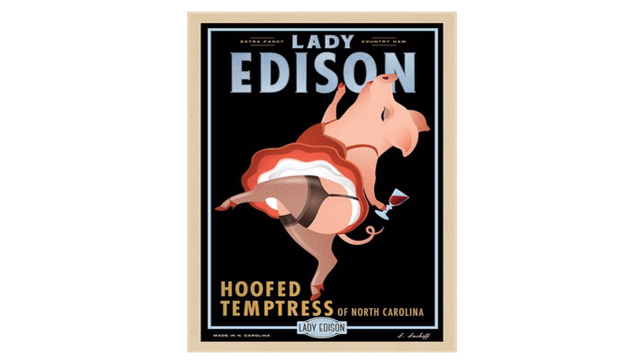

In my own work, I assert that in a patriarchal culture, to create subordination and maintain exploitation, women are animalized and animals are sexualized and feminized. Both women and the other animals are seen as consumable, animals literally, and women visually. Animals have been made into absent referents who disappear as living individuals to become meat and metaphor; in a patriarchal culture, women, too, are absent referents. Together, women and animals are, in fact, interchangeable absent referents. That woman shown cut up like a piece of meat next to the words “Break the Dull Steak Habit”? The dead animal was the absent referent in that image. Sadly, since my book, The Sexual Politics of Meat, first appeared at the end of 1989, images that use misogyny to sell meat and dairy and that animalize women have further proliferated.

Since early 1990, readers have sent me examples of the animalizing of women and people of color, and the feminizing, sexualizing, and racializing of domesticated animals – see for example here. From these, I created The Sexual Politics of Meat Slide Show in which I try to show how the circulation of oppressive images without an interpretative or explanatory frame commits discursive violence that allows for a material form of violence. Experiencing the slide shows, viewers are urged to look with resistance, to recognize that images can’t be unanchored from their referent and to refuse to consume the images on their own terms.

In advertisements about female farm animals, I find attitudes that fuel the current rollbacks on reproductive freedom and access to abortion. To control fertility one must have absolute access to the female of the species. Cows, sows, chickens, and female sheep are exploited in ways that merge their reproductive and productive labor. In his stance against abortion, one state legislator argued, “If a cow carries a dead fetus to term, why shouldn’t women?” We can find advertisements about cows asking, “If she weren’t pregnant what would she be doing?” In their advertisements aimed at animal agribusinesses drug companies depict sexy, buxom animals who want to be pregnant, who want to give the farmers one more sow per year. A chicken holds her sexualized, hairless leg out, she wants those drugs too, wants to be the subservient reproducer. “Keep me pregnant down on the farm.” Misogyny is hiding behind the depiction of sexualized farmed animals. The misogyny disappears behind the acceptable use of other animals because they are immaterial, absent referents.

We don’t realize that the act of viewing another as an object and the act of believing that another is an object are actually different acts because our culture has collapsed them into one. But those feminists in 1968 understood this. And we could, too.

Carol J. Adams is the author of The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory, now in a Bloomsbury Revelations twenty-fifth anniversary edition. This short animation by the artist Suzy González tells Adams’ story of becoming a feminist and a vegetarian and writing The Sexual Politics of Meat.