Lucy Mayblin

Successive UK governments over the past 20 years have explicitly represented working as a virtuous activity which provides personal fulfilment and allows the individual to contribute to society – economically and also socially. Receiving welfare benefits is, within this rationale, generally undesirable and, as far as possible, should be minimised. The current Conservative government is no exception. The Work and Pensions Secretary, Iain Duncan Smith, feels so strongly about the need to get more people into work that he has pushed through new rules to force up to 1 million disabled people into work, describing work as, amongst other things, good for one’s mental and physical health. Massive cuts to the welfare system are to be used to end long term benefit dependency and propel those deemed to be ‘feckless’ into employment.

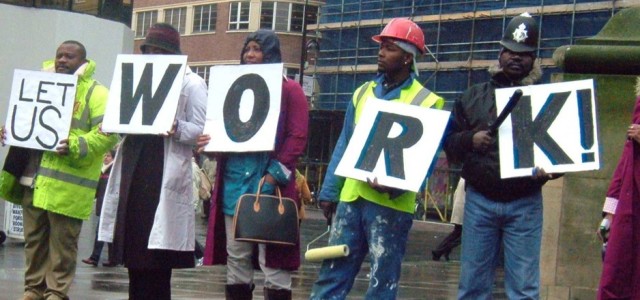

Yet it is illegal for the vast majority of asylum applicants in the UK to take employment while they are waiting for a decision on their application. In the absence of an income, asylum seekers receive cash welfare payments which amount to 50% of job seekers allowance, delivered through a separate welfare system. Asylum seekers are therefore banned from working, are forced into long term unemployment, and then the state has to pay for their living costs. To paraphrase Rosemary Sales, asylum seekers are cast as the underserving at the same time as being denied the means (work) by which they might redeem themselves. Yet preventing asylum seekers from working creates significant costs for the state at the same time as ensuring that asylum seekers are living in situations of poverty, which we leads to further costs (such as those associated with health problems). These two policy agendas, around the work and welfare rights and responsibilities of citizens on the one hand, and asylum seekers on the other, are completely at odds with each other.

In March this year I started a 3 year project funded by the ESRC to analyse this policy area, one which is fraught with contradictions and controversies. The first phase has involved gathering together a large body of texts on the topic of the right to work for asylum seekers from the moment the work ban was brought in in 2002, to the present day. That’s all of the records of the parliamentary and Lords debates, media articles in all major newspapers, think tank reports, academic research reports, voluntary sector reports and campaign materials, policy impact assessments, political speeches, and a host of other publications.

I gathered together 449 texts and used data analysis software to code it. This means that I identified all of the sections of text that corresponded to a particular argument. In the end, after a couple of months of coding, at the touch of a button I could find out how many times a particular argument was made, in what kinds of contexts, and by who.

So what did I find? I found that those who challenge the policy are from a wide range of backgrounds. They are politicians, think tanks, commentators in both right and left wing newspapers, European Union policy makers, trades unions, and of course campaigning and support organisations that work with asylum seekers and refugees. The arguments that these objectors make are wide ranging. From making the case that asylum seekers are too much of an economic burden and should be allowed to work to pay their own way, to suggesting that it has a negative impact on the mental health of asylum seekers, or suggesting that the public would look more favourably on asylum seekers if they worked.

These arguments are then made in a very wide range of contexts, from newspapers, to campaign leaflets, trades union webpages to think tank reports. And importantly, in parliament, in the Lords, in a variety of parliamentary committees, inquiries and reports. These sources draw on a large body of evidence compiled by inquiries, academic researchers, third sector investigations, and commissioned research projects.

But what is most interesting is the case against giving asylum seekers the right to work. This argument is made by a very narrow range of people –politicians in senior positions in the party in power, and Home Office spokespeople. These people give one main justification for the policy: if asylum seekers are given the right to work, more will come to the UK. I call this the pull factor thesis.

In contrast to those arguing for the right to work, no evidence is ever presented to support this claim that more asylum seekers will come to the UK if they are given the right to work. In fact, the evidence is quite the contrary. Researchers have done quite a lot of research into this, and several reports have even been produced for the Home Office. All of them, over the past 20 years, have consistently found asylum seekers to have little knowledge of the UK before they come here.

Often they are not able to exercise choice about their destination country as they have paid smugglers who constrain their choices. Where they are able to choose, they come to the UK because of a combination of having family or friends here, and having an idea of Britain as a fair country where the rule of law and human rights are respected so they will be safe. Vitally, histories of colonial relations are one of the most significant determining factors. Often asylum seekers do not know the legal intricacies of the asylum process, and it is very rare in the research to find examples of people who knew about their socio-economic rights before arriving. Whatever the policy, most people assume they will be expected to work and pay their own way and are horrified and confused to find that they will be prevented from doing so.

This is quite a weighty body of evidence, it isn’t one or two studies, and it doesn’t take a lot of digging to find it. So how can we make sense of the fact that the policy is based on a fallacy? I argue that we can understand it in terms of the concept of complexity reduction. To paraphrase Bob Jessop, complexity reduction is fundamental to our ability to ‘go on’ in the world (Jessop, 2009). We all attribute meaning to some aspects of the world rather than others because the world cannot be grasped in all its complexity, particularly not in real time. In order to describe or interpret real world events, as well as make decisions, policy makers must focus selectively on some aspects of the world at the same time as excluding others. In doing this they, and we, create stories about what is going on, in the case of social and political phenomena this is to make sense of what is usually an extremely complex set of interrelated variables that are difficult for individuals to comprehend.

In no context is this more the case than in international migration. For administrative purposes, politicians and civil servants like to make a very clear distinction between economic migrants and refugees. You will hear this a lot on the news, almost every policy maker interviewed on TV about the refugee crisis will talk about the need to distinguish between economic migrants and refugees. This is in fact a gross simplification of the real situation because of course it is entirely possible for someone to have been persecuted but also have hopes and dreams for the future, which like the rest of us probably involve working.

But in policy terms, once you construct this simplification, that the two are completely separate, what do you do? You say economic migrants work, asylum seekers don’t. If they want to work, they obviously haven’t been persecuted. On this basis you assume that economic migrants are aware of their options, research possible migration destinations, and will choose a destination where they will be able to gain employment. The asylum route, under this rationale, would provide an easy way for economic migrants to get into the UK and work legally.

The fact that this picture does not match the complexity of the situation on the ground is not important. It is a simple story that can be told over and over again and to that extent it becomes the truth, or a truth. And vitally, it appears to make sense to a large number of people who are likely to have little expert knowledge of asylum and can therefore be easily be deployed in media interviews. Once a simplification such as this has become sedimented it is very difficult to successfully contest a policy. As I described earlier, evidence is actively ignored.

The real question for policy analysts, academics and campaigners, then, is what modes of contestation to entrenched policy narratives are likely to be successful and under what conditions? While foregrounding the contradictions between the asylum agenda and the work and welfare agenda is one place to start, there is a risk of ending up in a race to the bottom. What is needed is a much more nuanced discussion about the rights of asylum seekers to work, and the rights of all to be supported, and not impoverished, where working is not possible. What we therefore gain from looking at these two punitive policy areas in tandem is not a race to the bottom but the opening up of a critical space to challenge both.

Further Reading and References:

Find out more: http://asylumwelfarework.com/

Jessop, B. (2009) Cultural Political Economy and Critical Policy Studies. Critical Policy Studies 3(3-4): 336-356.

Mayblin, L. (2014) Asylum, Welfare and Work: Reflections on Research in Asylum and Refugee Studies, International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 34(9/10)

Matthew, P. (2012) Reworking the Relationship Between Asylum and Employment, London: Routledge.

Sales, R. (2002) The deserving and the undeserving? Refugees, asylum seekers and welfare in Britain, Critical Social Policy, 22(3):456-478.

Lucy Mayblin is ESRC Future Research Leaders Fellow in the Politics Department at the University of Sheffield. Her previous research analysed the connections between Britain’s colonial past and asylum policy today –a book based on this work, ‘Asylum After Empire’ will be published by Rowman and Littlefield International in 2017. Lucy’s current research focuses on the politics of asylum seekers’ access to the right to work.