Mandisa Malinga (University of South Africa and University of York)

Unemployment is at the centre of the recent attacks on migrants in South Africa. While these attacks have mostly been referred to as Xenophobic, others have used the term Afro-phobia, as it is specifically African migrants who are targeted. Among the videos and images and commentary that have surfaced amidst these attacks several individuals have claimed that migrants are the reason why their sons and daughters are not employed, suggesting that migrants take the jobs that they believe could be reserved for South African citizens. Having recently completed fieldwork on precarious employment and fathering in South Africa, these claims do not surprise me as the data suggests that this is a belief shared by many, particularly unemployed South Africans.

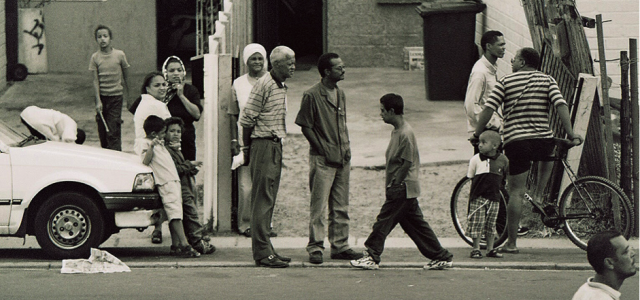

Women as well as men are involved in day labour. However,my research looked only at men and the chosen street corner also happened to only be occupied by men. In my research I looked at constructions of fatherhood and fathering practices among African men looking for work on the side of the road in South Africa. For those not familiar with this phenomenon, men gather at street corners (particularly in industrial areas) or in areas where warehouses that sell construction material can be found. The majority of the men are construction workers and they can take any job ranging from gardening to tiling and carpentry. Many of these men have no formal schooling and live precarious lives- moving from one place of residence to another, and from one street corner or ‘job site’ to another. Some even become homeless in the process as they face ‘shame’ for not being able to confirm to masculine ideals that construct men as providers. They would rather sleep under a bridge than go home and admit to their inability to provide for their children and families.

During my fieldwork I found that the men on a particular street corner were not only South African men, but also from other African countries. Interestingly, out of 56 men, only four had actually been born in and lived all their lives in Cape Town, others having moved from rural parts of South Africa (and elsewhere) in search for work. While this proves to be one way of making a living for some (even sometimes leading to full-time job opportunities), it can be stressful for others with such a street corner becoming a ‘breeding site’ for hatred towards migrants. This was illustrated by how boundaries were created between South African men and those from other African countries, where certain parts of the street corner are only reserved for South African citizens who are at liberty to move freely from one section to another, while migrants are restricted to one part of the street.

Anyone who has a job they need done – in their private home or on a construction project- can drive up this street and ‘pick’ any one of these men for the job. It sounds easy enough. However, many potential employers (or as often referred to ‘clients’) can be intimidated as there can be between 5 and even 10 men running up to vehicles to offer themselves for the job. Often, this has been reported to turn violent as everyone is ‘desperate’ and needs the job, because the opportunities for such work can be really low. This then, from my conversations with the South African constituency on this street corner, has lead them to reject the presence of migrants as they believe the competition is already high among ‘themselves’. They also believe that migrants often do not conform to the general rate they are expected to charge for a job per day and are thought of as undercutting and providing ‘cheap labour’ which makes them more attractive to employers than South African labourers.

Having spoken to different groups of men on this street corner I have found this not to be the case. First, the majority of, if not all, migrants on this street corner had formal schooling and had received some form of post-school training. And because of this, they are often in a position to ‘sell’ their skills for more permanent opportunities. Also, because they have training, they are often paid higher than some of the South African men who were mostly general labourers with no post-school training. This is consistent with Blaauw, Pretorius, Schoeman and Schenick’s (2012) finding which suggested that Zimbabwean day labourers in South Africa were often better qualified and therefore received higher wages.

Besides the hatred towards others, resulting from the competition for jobs, all men who look for work on street corners suffer in some way while trying to make a living. Among the many ways in which they suffer is their separation from their families. For migrants, leaving their families back in their home countries is never easy and they often do not go back regularly because of the costs involved. For others, not being able to provide often means that they are separated from their partners and often their children are taken from them too. This is what I believe to be part of the reason why the men I interviewed struggled to define fatherhood outside of the bounds of economic provision. For all these men, being a father means being able to provide, which in their case, essentially means being on the side of the road looking for work.

What is most concerning is that being on the side of the road and getting a job even for the day or for a few hours in a day does not guarantee that these men will get paid as many of them are cheated out of their earnings. Many of them are told (once they get to the work site) that they do not deserve to be paid the daily rate they charge as they are picked up on the side of the road (and are therefore supposedly desperate). This suggests an undervaluing of the skills these men bring to their jobs, and as a result, underpayment.

It is at present hard to imagine the unemployment in South Africa taking a turn in a positive direction, and this threatens the lives of those involved as well as the well-being of their families and children. There is however a lack of awareness among those who use the services of day labourers of the struggles these men face, of the lengths they go through just to be on the street corner, as well as the abuses they suffer while on the job. If anything, day labourers are often thought of as criminals who threaten the businesses surrounding the street corners they occupy. This often contributes to stereotypes that make it very difficult for many hardworking men to be trusted. While there are many negative stories that have come out of my fieldwork experience, there have been some positive stories and often these are not told. Through this study, I hope to tell much more of these stories particularly from a South African perspective.

Reference:

Blaauw, P., Pretorius, A., Schoeman, C., & Schenck, R. (2012). Explaining migrant wages: The case of Zimbabwean day labourers in South Africa. International Business & Economics Research Journal, 11(2). 1333-1346.

Mandisa Malinga is a South African PhD student currently based in the Centre for Women’s Studies at the University of York as part of a split-site scholarship.