Tony Platt, San Jose State University

The upcoming International Day of Remembrance for the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade (March 25th), and twentieth anniversary of the Rwanda genocide (April 7th) provide an occasion to examine how we publicly commemorate inhumanity at its worst.

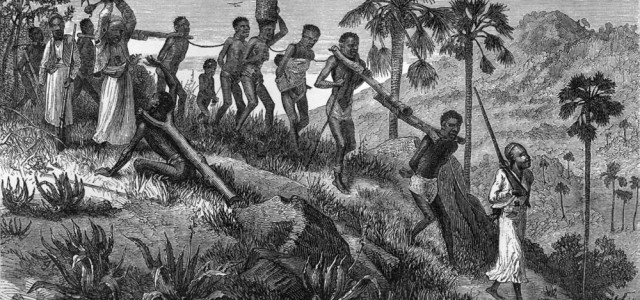

It’s taken a long time for the Western countries that profited from the 300-year trade in twelve million Africans to begin to come to terms with the sorrowful history of the Middle Passage and chattel slavery.

Motivated by the 150th anniversary of the political decision to abolish the slave trade, a few English museums broke the silence. “What does a sweet cuppa have to do with a terrible crime against humanity?” At the Museum of London Docklands you will find a powerful exhibition on “Sugar and Slavery” that answers this question and reveals the centrality of the fourth largest slaving port in the world to the country’s economic development. Similarly, an exhibition at Liverpool’s Maritime Museum’s leaves no doubt that every leading entrepreneur in the region cashed in on the buying and selling of human beings. And if you want to more deeply understand the who, how, and long-term consequences of British slave-ownership, there’s an excellent website at University College London.

The many public events in England to commemorate the abolition of the slave trade were/are typically ephemeral or tokenistic. If you visited the British Empire and Commonwealth Museum in Bristol before 2008, you would have learned about the ties between slavery past and racism today. Now it’s shuttered. As you walk through the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and National Maritime Museum in Greenwich looking for representations of the slave trade and abolitionist movements, don’t blink or you’ll miss them.

However closely you look for public acknowledgment of the slave trade in Portugal, you’ll find nothing but scrupulous amnesia. Tourists watching The Lisbon Story in a museum in the main square are spared any images or information about the country’s pioneering role in the African slave trade. And the fascistic Monument of the Discoverers in nearly Belem still celebrates the heyday of the Empire and unity with South Africa’s apartheid regime.

By contrast, the Netherlands is curently undergoing a tense self-examination of its prominent role in the buying and selling of some 600,000 Africans shipped from its fortresses in what is now Ghana. In 2013, the Scheepvaart Museum in Amsterdam hosted a popular exhibition about the deaths of 664 African men, women, and children on board a Dutch West India Company slave ship. “The story of the Leusden was never told in Holland until now,” historian Leo Balai told me. “It was the largest murder in the history of the slave trade.” Also in 2013, the African Studies Center in Leiden developed an in depth resource that documents Dutch involvement in the slave trade.

At about the same time, the University of Amsterdam’s Library curated an extraordinary collection of original documents, artifacts, and images associated with the “lucrative merchandising” of Africans. While slavery was illegal in Holland, noted the catalogue, “in the colonies the white conscience was not bothered by such scruples.” After visiting the exhibition, I took a canal trip with the recently created Black Heritage Tours, its guides eager to point out the sites of banks and businesses that profited off slavery, and racially offensive carvings of clownish Moors or gapers.

This introspection about the country’s past has ignited small but determined public protests against the annual celebration of St. Nicholas when the Santa Claus character is typically accompanied by Black Petes, played by white men in blackface; and when children and adults all over the country buy and display racially themed knick-knacks, including a cosmetics kit with a sponge and black powder. Millions of people have expressed support of Black Pete as an important cultural tradition, echoing the fierce defense of confederate symbols in American South. Yet, a national conversation about race has begun in the Netherlands which will not be easily silenced.

Meanwhile, in the United States the enduring legacies of slavery “stick like a fishbone in the nation’s throat,” as historian Edward Linenthal observed. There is still no day set aside to celebrate the Emancipation Proclamation. Despite an enormous amount of scholarship on the topic, public recognition of slavery is timid, with the guardians of cultural instititions generally unwilling to dredge up smoldering enmities or sully glorious stories of the nation’s origins. Many museums deal with the contributions of specific ethnic groups, but what’s absent is any national recognition of the deep wounds and ruptures generated by racism, and of slavery as a foundational event. Hopefully, this will be rectified next year when the National Museum of African American History and Culture is scheduled to open and promises to recast “Black History” as the “American story.”

It took Great Britain more than a century after the beginning of its imperial decline to initiate an honest discussion about the legacies of the slave trade. Hopefully, the United States will not have to wait for future generations to explore how the past bleeds into the present.

As for genocide, the record of commemoration is much more extensive, but also uneven. During the 20th century developments in weaponry made the cavalry obsolete, and mass killings of non-combatants through malice and neglect were so commonplace that the dead were “past counting,” as a witness to the genocide of Armenians noted in 1916.

The number of victims generated by what Eric Hobsbawm calls “the monster of total war” is numbing: two-thirds of European Jews murdered by the Nazis; two million, give or take a million, dead at the hands of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia; maybe as many as a million Tutsi victims in Rwanda; not to mention hundreds of thousands of corpses generated by political violence, ethnic cleansing, and state terrorism in the former Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, Franco’s Spain, and Latin America’s “dirty wars” and U.S.-led counterinsurgency campaigns.

Since World War II, there’s been a boom in memorial culture. Following the opening of the Yad Vashem Holocaust History Museum in Israel in 1973, the proliferation of holocaust memorials, museums, exhibitions, and centers in the West has promoted ritualized introspection, but rarely critical thought about the past, as reflected in the anodyne warning “Never Again.”

Of the world’s most powerful nations, only Germany has seriously grappled with the contradiction of barbarism within modernity. The combination of grassroots activism and governmental acceptance of responsibility for crimes against humanity under Nazism has generated extraordinary scholarly debates, educational programs, and investigations about the systemic roots of genocide, as well as hundreds of installations at “authentic sites” of terror. “Where in the world,” asked a former Israeli ambassador to Germany, “has one ever seen a nation that erects memorials to immortalize its own shame?”

France, on the other hand, has only recently begun to explore its complicity in the Holocaust. In the summer of 2012, I joined a somber, silent group of Parisians to see, for the first time, an exhibition at City Hall about Jewish children deported to their deaths during World War II. The discomfort was palpable.

Similarly, the United States, which leads the world in the number of Holocaust memorials, fails to confront its own atrocities. In California, where I live, the state’s public history sanitizes the genocide of Native peoples and ethnic cleansing of Chinese immigrants as a narrative of ‘Progress’.

In Latin America, Argentina leads the way with public education about the “dirty war,” during which the military dictatorship, with active American support, disappeared as many as 30,000 activists between 1976 and 1983. The victims are honored at the Monument to the Victims of State Terrorism in Parque de la Memoria in Buenos Aires, alongside the Rio de la Plata, where corpses were dumped; and the perpetrators are remembered at a museum on the former site of the Navy School of Mechanics (Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada), where prisoners were matter-of-factly tortured.

As developing, impoverished countries, Rwanda and Cambodia face the simultaneous challenges of rebuilding their economies, reonciling political and ethnic factions, and commemorating genocide. In both cases, the national governments have created mass grave sites and lieux de mémoire, plus preserved and publicly displayed the skeletons of some victims as a reminder to the international community and as a site of thanato-tourism. Western critics who have raised concerns about state-regulated remembrance should be on guard against cultural colonialism, and keep in mind that in Cambodia many killing fields are now working farms; and that in Rwanda collective funerary practices take precedence over individual rituals.

Some wealthy countries and NGO’s are encouraging the use of new scientific techniques to “match bodies without identities with identities without bodies,” in the words of Argentinian forensic anthropologist, Luis Fondebrider. But, as participants noted at a conference in Manchester last September, science for the most part is irrelevant to the process of recovery in mass murder. It is impossible to identify individual victims of genocide whose remains were tossed into unmarked pits, burned in ovens, degraded by the elements, and moved from grave to grave.

To do justice to the past is primarily a political, social, and cultural rather than scientific challenge. We’ve certainly improved on Germany’s “move-on mentality,” shaped by the Cold War aftermath of World War II, and on Spain’s “pacto de silencio” in the wake of Franco’s death in 1975. But too often remembrance of human-made tragedies is reduced to prescribed rituals and sentimental pabulum rather than a grappling with whether slavery and genocide are uniquely dreadful or dreadfully common features of our interdependent world.

1. The Middle Passage was the stage of the triangular trade in which millions of people from Africa were shipped to the New World as part of the Atlantic slave trade. Ships departed Europe for African markets with manufactured goods, which were traded for purchased or kidnapped Africans, who were transported across the Atlantic as slaves; the slaves were then sold or traded for raw materials

References:

Leo Balai, Slavenschip Leusden. Utrech: Walburg Pers, 2013.

Zygmunt Bauman, Modernity and The Holocaust. New York: Random House, 1993.

Thomas Bender, A Nation Among Nations: America’s Place in World History. New York: Hill and Wang, 2006.

Nigel Eltringham, “The Past is Elsewhere: The Paradoxes of Proscribing Ethnicity in Post-Genocide Rwanda,” in S. Strauss and L. Waldorf, eds., Remaking Rwanda: State Building and Human Rights after Mass Violence. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2011.

Arnon Grunberg, “Why The Dutch Love Black Pete.” New York Times, December 4, 2013.

Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Extremes: A History of the World, 1914-1991. New York: Pantheon Books, 1994.

Edward T. Linenthal, “Epilogue: Reflections,” in James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton, eds., Slavery and Public History: The Tough Stuff of American Memory. New York: The New Press, 2006.

Phillip Lopate, “Resistance to the Holocaust,” in David Rosenberg, ed., Testimony: Contemporary Writers Make the Holocaust Personal. New York: Times Books, 1989.

Tony Platt is the author of ten books dealing with issues of race, inequality, and social justice in American history. He is a member of the editorial board of Social Justice and Visiting Professor of Justice Studies, San Jose State University, California. He blogs on history and memory at: http://GoodToGo.typepad.com.