Robert Moore, University of Liverpool

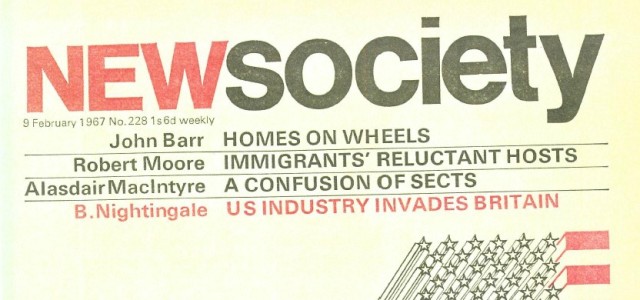

It is nearly fifty years since the publication of Race, Community and Conflict, a study of Sparkbrook, Birmingham, co-authored with John Rex (and reported in New Society in 1967). Unusually for a sociology book, the publication attracted widespread public attention. A leader in The Times suggested that we had shown the need for tighter controls on non-white immigration from the ‘New Commonwealth’, while Enoch Powell wrote a long rant against New Commonwealth immigration in the guise of a review of it in the Daily Telegraph.

There was widespread coverage in West Midlands newspapers including serialised excerpts from the book. While we were denounced by some officials in the City of Birmingham, within a few years our work was incorporated into the official history of the city. John Rex and I took part in television programmes and radio interviews. We were consulted for a prime-time BBC programme, but not included in the broadcast in which the local MP denigrated our analysis. The BBC cited the Race Relations Act in denying us a reply in The Listener.

Academic journals (with the exception of The British Journal of Sociology) and the weeklies reviewed our work. The book became and remains one of (if not the) most cited British sociology monograph. Unusually for a British publication it was noticed in the United States with citations in the American Journal of Sociology, the American Sociological Review and Social Forces. In the wider political sphere, the book made a contribution to the inclusion of housing in an amended Race Relations Act.

Whilst Race, Community and Conflict stimulated public debate it was primarily a sociology book which explored how we might understand peoples’ lives in a rapidly changing city, linking wider social and economic changes to the lived experience of people in one part of that city. We drew on two main traditions in our analysis; one was the Chicago School, especially the work of R.D. McKenzie. Surprisingly this attracted little critical attention, perhaps this theoretical field was thought to belong to urban geography rather than sociology. Our second, more Weberian propositions, around the idea of ‘housing classes’ did become a focus for widespread discussion and debate amongst sociologists. It was an idea that was challenged both through empirical research and critical discussion. I have outlined the initial impact and the direction of some of the key debates in a recent article in Sociological Research Online.

The publication of Race, Community and Conflict also marked the beginning of my career in sociology (my second career, the first having been in the Royal Navy). Today I occasionally observe suppressed embarrassment on the face of a young colleague who has not realised that the author of a book they read for A-level is still alive. Perhaps, then, I am at a good point from which to look back on a life in sociology and race relations.

By the mid-1960s, ‘coloured immigration’ was an issue central to political debate, with both the main parties wanting to show the electorate that they could be tougher than the other on immigration – until it became a ‘Celtic Tiger’ Ireland was the main source of immigrants to the UK, but this seldom featured in the politics of immigration. A pivotal moment was the publication of Harold Wilson’s White Paper Immigration from the Commonwealth in 1965.Then, as now – except for the most rabid racists – the debate centred around competition for resources, especially housing. The public were not altogether clear whether immigrants were the victims of housing shortages, or the cause of them. The Wilson White Paper closed the argument down; immigrants were the cause of the problems that city-dwellers faced. Labour joined a ‘Dutch Auction’ on immigration.

I pointed out in an article in Venture that the Labour government had surrendered the grounds on which demands for further immigration restrictions could be resisted – the only argument now was about numbers. We were on a slippery slope, leading eventually to competition over the numbers removed or deported. This provoked an angry response from a junior Minister who implied that anyone who suggested Labour would go a step beyond the proposals in the White Paper just did not understand the liberal, tolerant, nature of the Labour party.

Shortly thereafter we had the (Labour) 1968 Commonwealth Immigrants Act, the 1969 Immigration Appeals Act which restricted access to appeals by persons refused entry to the UK, the 1971 Immigration Act (a Labour measure, enacted by the Conservatives), followed by almost continuous restrictive legislation on citizenship, immigration and asylum continuing into the 21st century. Lord McNair’s comment on the 1988 Immigration Act could be applied to every subsequent measure:

“another mean-minded, screw tightening, loophole closing concoction imbued with the implicit assumption that almost everybody who seeks to enter this demi-paradise of ours has some ulterior, sinister and very probably criminal motive and the sooner we get rid of him the better” (House of Lords 4th March col 389)

The earlier legislation removed the rights of both Commonwealth and UK passport holders to come to the UK, and then restrictions were placed on family reunion. But the numbers game did not end there because certain newspapers provoked alarms about illegal immigrants, asylum seekers and refugees, then overseas students and migrants from the eastern parts of the EU. Immigration policy passed beyond theory and data-analysis, beyond reason and common sense. ‘Bogus’ and ‘illegal’ became commonplace epithets in discussions of immigration.

The inhumanity with which the immigration restrictions were implemented in the earlier years were described by Tina Wallace and myself in 1975 in Slamming the Door: the Administration of Immigration Control, this book received no public response and no reviews, though some journalists plagiarised parts of it over the next few years. Now recent tightening of restrictions on legal entry to the UK in the face of a demand for labour and the availability of people in war-torn or impoverished countries has led to an increase in trafficking. Labour-trafficking has become a highly profitable criminal activity worldwide. Victims of trafficking find themselves in forced labour, or near slavery conditions, without rights and with no protection from employers or the state.

We are all immigration officers now. Borders have moved inside national boundaries. Universities and hospitals are expected to patrol this internal border and social benefits are denied to a range of people with immigration statuses that confer less-eligibility. Your neighbour may be in the country but they may not be part of it. Discrimination on the basis of social class features heavily in immigration policy; wealthy migrants can buy their way into the UK whilst poorer overseas migrants are condemned to trafficking, exploitation and legal insecurity and those from within the EU face increasing restrictions on their access to goods and services.

When John Rex and I were working in Birmingham, people from India, Pakistan and the Caribbean were just seen as ‘immigrants’, a subordinated minority. The presence of these same (now older) immigrants, their descendants and newer arrivals, is now unremarkable. It is the all-white parts of Britain that seem strange. Minorities may be discriminated against but they accept subordination no longer. In the late 1960s minority populations mobilised against police harassment and violence. The case of the ‘The Mangrove Nine’ in 1970 resulted from resistance to police harassment and attempts to close down the Mangrove restaurant in Notting Hill. The persons charged were acquitted of all serious charges. Ten years later ‘The Bradford Twelve’ were similarly acquitted having argued ‘self-defence’ against charges. But two years earlier the Asian population of Southall had not fared so well when the police rioted, doing widespread damage to community property, inflicting injuries and causing the death of a school teacher. The year 1981 also saw resistance to heavy-handed policing and harassment in Brixton, Birmingham, Leeds and Liverpool. Although the period after the publication of the McPherson Report saw substantial changes in policing, deaths in custody and police shootings continued to provoke responses, notably in 2011 when the shooting of Mark Duggan led to rioting across London which later spread to other English cities.

For their part the police began to understand that effective policing is ‘policing by consent’ requiring the support of a population which has confidence in them. Training, monitoring, the recruitment of minority officers, outreach initiatives and responses to human rights and equalities legislation have all led to changes in operational practices in police forces. There remain nevertheless examples of failed efforts to change police culture and practices. Police involvement in immigration enforcement and anti-terrorism activities has also hindered more positive developments.

Today the ‘ethnic minority’ population is a political force in many cities, with a strong voting base in (mainly) inner-city wards, Councillors and civic leaders are regularly drawn from black and Asian populations. Although under-represented, Members of Parliament are elected from these populations to both sides of the House of Commons.

In Birmingham in 1965 the immigrant population was a working class population with only a small proprietor class serving the local population. Today there is an upwardly mobile black and Asian middle class created by recruitment into the public sector and, increasingly, the private sector, as professional and managerial employees. Perhaps most conspicuously the recruitment of overseas doctors has contributed to the growth of this professional class. There is also a significant entrepreneurial element in the minority population, including self-made millionaires. Together these constitute a population largely removed from the everyday concerns of inner-city black and Asian citizens. More affluent ethnic minority citizens have joined their white peers by moving to the suburbs; the concentrated minority populations are dispersing, to be replaced in the inner zones by younger people – many of whom will themselves be black or Asian, recent migrants or refugees. In 1965 we studied an inner city area which we said had something of a ‘colony’ structure, not a ‘ghetto’, but perhaps with the capacity to become one. Whilst the ‘parallel lives’ and ‘white flight’ rhetorics have been shown to be largely unfounded it probably remains the case that the more close-knit inner-city centres of minority populations continue to provide a degree of social, political and economic support.

An important argument in Race, Community and Conflict was that, unlike the wholly free market processes of urban ‘invasion and succession’ in Chicago, a significant part of the UK housing supply was a publicly-run service providing housing according to need. Part of the local population relied upon this public provision. Thus immigrants needing housing were seen to threaten the interests of working class people who aspired to a home of their own in the form of a council house. This assumed threat to the working class’s stake in the welfare state has been played upon as part of anti-immigrant agitation since the 1960s and is currently incorporated in wider political debates that set the poor against the very poor, the middle against the poor, and the old against the young. The rhetoric that consigned immigrants to a less-eligible position is now increasingly turned against those very sections of the population that thought they had the greatest stake in the welfare state. This was not a development that John Rex and I foresaw.

The world of ‘race relations’ is thus much changed since I ventured into Sparkbrook in 1965 and one notable change is that this world is now also addressed and challenged by black and Asian colleagues. Yet in one important respect little has changed; on the question of immigration it was The Times and Enoch Powell that prevailed – theirs is now the rhetoric of all political parties, who continue the Dutch Auction, the dismal race to the bottom on immigration.

Robert Moore is emeritus professor of sociology at the University of Liverpool.