Stephen McKay, University of Lincoln [pdf]

If there is a reliable strategy for getting non-resident parents to pay child support towards their former partners then it has long eluded British Governments. Some twenty years after the introduction of the Child Support Agency (CSA), many of the key aspects of the original policy framework have been abandoned, and parents are increasingly expected to resolve matters between themselves. The point that separating couples are often unable to reach satisfactory solutions – a cause of the problems that led to the creation of the CSA in 1993 – has been largely set aside.

A statutory Child Maintenance Service remains (gradually taking over from the CSA), but one that parents do not have the incentive to use because of the imposition of new assessment fees and on-going collection charges (an application fee of £20, plus maintenance is reduced by 4% for the recipient, and increased by a hefty 20% for the payer. These collection charges are not levied when maintenance is set up privately).

In most countries, parents have a legal obligation to maintain their biological children. This applies regardless of the marital or relationship status of the parents. The separation of parents will often increase the risk that children will be raised in poverty, and so the payment of child support is one means of trying to reduce such a risk. Eurostat figures show that lone parents have about double the average poverty risk (using Eurostat’s data explorer). In some cases, there will also be a loss of contact between the child and one of the parents.

However, child support is not only about poverty. Many people believe that children should be maintained by their parents (rather than, say, a new step-parent). Others, though not all, tend to think that children should share in any higher living standards enjoyed by their parents (1). Even so, it quickly becomes clear that the ‘right’ way to set child support will call forth a range of different judgements about the role of the state compared with the role of the family, how far the state (including courts) should intervene in family life, and the obligations owed towards children. There are also difficult judgements about the right amount of money that is owed by parents to their children – and whether that should be determined as a matter of discretion, formula or family negotiation.

The CSA 1993

The impetus for setting up the Child Support Agency is often attributed to Margaret Thatcher. In a speech in July 1990 she noted that “marriages may break down, parenthood is for life” and that “only one in three children entitled to receive maintenance actually benefit from regular payments” . The Department for Work and Pensions was also acutely aware of the growing number of lone parents, the majority of whom were receiving Income Support. The twin powers of the financial motives (child maintenance collected would be used to cut benefit payments pound-for-pound) and the more moral agenda created the momentum for the introduction of a Child Support Agency in 1993.

Some of the details appeared to have been influenced by other agency systems working in the US – Wisconsin is often identified as a particular model – and in Australia. A key feature was that lone parents receiving means-tested benefits would be forced to apply for child support, unless they had ‘good cause’ not to, whilst for others outside of the benefit system it would be optional. This arrangement brings to mind Titmuss’s phrase that separate services for the poor tend to be poor services (RM Titmuss 1968 Commitment to Welfare), and so has it turned out.

Mrs Thatcher’s aim that the “whole process will be easier, more consistent and fairer” has never come close to being achieved. As early as 1994, writing for the Child Poverty Action Group, Alison Garnham and Emma Knights were able to point to considerable problems of implementation, owing to flawed computer systems struggling with a labyrinthine calculation formula, and the anxiety that the system was really adding pressure to existing arrangements rather than focusing on the stubborn group of non-payers who were widely seen as the target of the new arrangements (2).

CSA Reformed, New System 2003

Major reform was enacted from 2003 onwards (via the Child Support, Pensions and Social Security Act 2000), removing the complex calculation in favour of a set of simple percentages of income – with 15% / 20% / 25% of net income (for one, two, or three or more children). Child support levels would depend on a handful of pieces of information (such as overnight stays and the non-resident parent having other children) rather than the 100+ pieces previously required. Other reforms meant that non-working lone parents could keep up to £10 of any maintenance paid, whilst those in work could keep it all – significantly increasing the financial incentive to work, a strong theme at the time and subsequently.

These significant changes did little or nothing to stem the flow of problems. Following a 2006 report by the National Audit Office (NAO), new condemnatory superlatives had to be found for an agency long dogged by criticism. The Public Accounts Committee said that lack of progress had ranked “among the worst public administration scandals in modern times” whilst David Laws MP suggested, prophetically, that “The CSA has reached a dead end, and no amount of tinkering will get it working properly.”

The NAO had found that it was costing 70 pence to collect each £1 of maintenance – and yet a proportion of that would probably have been paid even in the absence of the CSA. The unpaid arrears of child maintenance had reached £3.5 billion and were continuing to increase. The proportion of parents receiving maintenance continued to hover at the figure of one-third that had caused such alarm in 1990. Their verdict was that “The [2003] Child Support reforms were a final but, in the event, unsuccessful attempt to deliver the policy behind the creation of the Child Support Agency in 1993” (John Bourne 2006). There is historical evidence to suggest that the administration of child maintenance had worked rather better under the Old Poor Law during 1576-1834 (T. Nutt 2006 The Child Support Agency and the Old Poor Law).

Henshaw Review, Voluntarism and Beyond

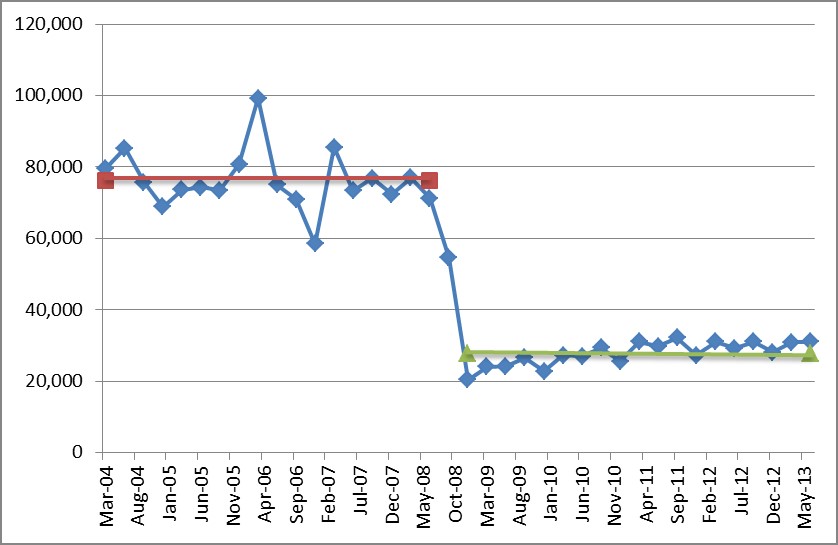

A new review of child support commissioned in 2006 from Sir David Henshaw, Recovering child support: routes to responsibility, provided something of a guide to future developments. It emphasised that parents should first try to come to their own agreements. Failing that, and only if the courts did not arrive at a relevant settlement, then there would be access to a state system as a safety net of last resort. It also suggested removing the requirement for lone parents receiving benefits to use the system. The reform enacting this in 2008 had an immediate impact on the flow of new cases to the CSA. As shown in Figure 1, within a few months the quarterly inflow of new work fell by around two-thirds. Such a drastic drop in workload did then enable the previously accumulated backlog of work to be addressed, and indeed the clearance times for dealing with new cases were much improved (around 88% of applications are cleared within 12 weeks, compared with around 30% in December 2004, but the 1990 White Paper Children Come First proposing the CSA had criticised the seven week average decision time of the courts as evidence of failure.) Important achievements, but somewhat akin to a bus service claiming shorter journey times by failing to stop to pick up most of the passengers.

Figure 1 – changes to obligation to use CSA among Income Support claimants, number of claims made to the CSA each quarter March-2004 to May-2013

Source: Child Support Agency Quarterly Summary of Statistics for Great Britain (June 2013).

Conclusions

To some extent the wheel has now turned full circle. Prior to the CSA, parents had the option of using the courts to assess and collect child maintenance, but otherwise had to rely on parental co-operation. Under the new arrangements gradually being introduced the emphasis returns to privately negotiated arrangements, albeit ones that take place in the shadow of a new statutory system. It is still too soon to be sure about the longer term implications of these reforms for the level and reliability of child support payments. Past DWP research has not been positive about the child support arrangements of those outside of the main system (Wikeley et al. 2008, Relationship separation and child support study, DWP Research report #503 ). Moreover, many private arrangements do not appear to be stable over time (Bryson et al. 2013, Kids aren’t free) At a time when benefits are being squeezed and wages are often static or falling, for many lone parents child support can be a vital source of income, but it is one that is increasingly fragile.

References:

(1) For a recent study see Bryson, C., Ellman, I., McKay, S. and Miles, J. (2013) ‘Child Maintenance: how much the state should require fathers to pay when families separate’, a British Social Attitudes report, edited by M. Phillips, London: NatCen Social Research.

(2) ‘Putting the treasury first: the truth about child support’ Child Poverty Action Group 1994).

Stephen McKay is Professor of Social Policy in the School of Social & Political Sciences at the University of Lincoln.