James Nazroo, University of Manchester [pdf]

When was the last time you heard a MP, let alone a minister, talk about ethnicity in terms of inequality? In mainstream policy discussion we appear to have moved into a ‘post-race’ world, where ethnicity is no longer considered to be a driver of disadvantage. Rather, mainstream policy focuses on ethnic identities that don’t fit; that is, ethnic identities that encompass attitudes and behaviours that are held to be insufficiently British. Although there are many grounds on which to challenge this– asking how we might theorise or define a notion of Britishness is one simple example – what concerns me most is how this ignores and aggravates underlying ethnic inequalities. The racialisation of ethnic minority identities, identifying identity as the problem, further undermines those so identified.

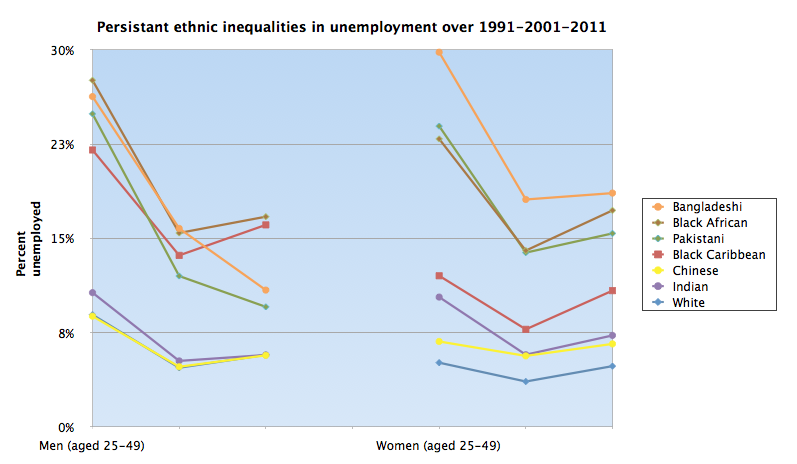

Without wanting to be equally crude in my analysis, I do think that it is reasonable to simply assert that ethnic inequalities – and the prejudice, discrimination and racism that underlie them – have persisted to some significant degree. We have not seen them disappear. In the employment sector, for example, our analysis of data from the Census shows that there has been little change in the large inequalities in employment experienced by people in ethnic minority groups. White men and women have maintained a consistent advantage over the past 20 years compared with men and women in almost all other ethnic groups.

This research is being carried out by the newly established ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE), based at the Universities of Manchester and Glasgow. Our core agenda is to understand the contemporary patterning of ethnic inequalities, to investigate how inequalities relate to the ways in which ethnic identities are perceived, acted upon and experienced, and to provide the knowledge and tools to enhance policy and public capacity to engage in this area. We propose that we need to both examine current data and understand how and why the patterning of ethnic inequality has changed over time. We can easily see that it is likely that changes in patterns of migration to the UK, in underlying economic (boom or recession) and political (war on terror) contexts, and in social dynamics (such as the rise of service industries) will all impact on ethnic inequalities. The core argument is that we cannot understand the present, or anticipate the future, without considering the past.

To do this CoDE brings together an interdisciplinary team using quantitative and qualitative approaches to understand how ideas of, and responses to, ethnicity have changed and what impact this has on contemporary ethnic identities and inequalities. We intend to provide the empirical foundations for innovations in both theory and policy. And in the UK context we can take advantage of the large body of historic and contemporary data to do this. The quantity and quality of survey data collected on ethnicity has increased over time, providing a unique opportunity to understand changes in the ethnic make-up of the population, the dynamics of ethnic inequality and identity and the factors that may be driving these changes. And the increasing access we have to data that study the same individuals over time means that we can examine processes operating at both the individual and ethnic group level. In addition, we are conducting case studies in four localities so that we can understand dynamics within specific contexts, as well as at a national level.

Our initial empirical work, supported by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation as well as the ESRC, has concentrated on analysis of Census data, and it is worth considering a few of the findings from that work. But an initial caution – data such as those obtained by the Census rely on a simple crude categorisation of people into ethnic categories. Such approaches cannot take into account how the meaning of a category changes over time (what does it mean to label oneself as Irish in 2011 and how does that compare with such a label in the 1980s?) and how this relates to the emergence of new categories, such as those relating to mixed identities; nor how the composition of a category changes (individuals may change their choice of category as their personal context changes, or as the meaning of the category changes, and in different periods different types of people might identify with a category – the issue of generation provides an obvious example of this); and, of course, categories use relatively crude and non-specific groupings (Indian and Black African are obvious examples).

Given my contestation of ethnic categories, it may seem odd that the first question I want to pose is how the ethnic composition of England and Wales has changed (2011 Census data from Scotland are not currently available). But examining this helps us understand shifts in context. An examination of the Census data shows that, in 2011, 14% of the population identified with a non-white ethnic group (an additional 6% identified with a White group other than White British), compared with 9% in 2001 and 7% in 1991. But we can also see what might be a growing complexity of ethnic identification and a rejection of standard categories – the size of ethnic categories with ‘Other’ in their title have increased by half in the ten years between the 2001 and 2011 Censuses. And the rise in the number of people identifying as mixed (a grouping that also increased by about a half between 2001 and 2011 to just over 2% of the population) might well reflect how the significance of ethnicity as a marker of separation might be changing. Indeed, one in eight households now contain people from more than one ethnic group (excluding, of course, those with only one person).

Given the increasing size and apparent diversity of the England and Wales ethnic minority population, it is worth considering what this means in terms of the fit between ethnic minority identities and Britishness. Some simple descriptive findings from our analysis of the Census suggest that regardless of how the issue is defined it is hard to see what the problem is. Although 20 per cent of the population of England and Wales have an ethnic identity other than white British, only nine per cent have a non-British national identity, only nine per cent have a foreign passport, only eight per cent have a foreign main language, and only two percent do not speak English well. Perhaps surprisingly, well over 80 per cent of people in the predominately Muslim Pakistani and Bangladeshi ethnic groups say they have a British, English, or other UK national identity; a similar figure to that for people in the Caribbean ethnic group.

And these markers of ‘integration’ are reflected in analysis of residential segregation, which illustrate that rather than becoming increasingly segregated the ethnic minority population has become more evenly spread across England and Wales and that this ‘spreading out’ has accelerated in the past ten years. Indeed, cities labelled by politicians as ‘segregated’ are in fact the most diverse.

Returning to the question of inequality, rather than increasing integration we see continuing inequality in the field of employment (as described briefly above and in CoDE 2013).

For example, Black Caribbean and Black African men and women have had persistently high levels of unemployment over the past twenty years, more than twice as high as the White rate and in some cases more than three times as high. And while Pakistani and Bangladeshi men and women have seen large falls in unemployment over the period 1991 to 2011, they continue to have much higher unemployment rates than White men and women and the fall is mainly a result of a large rise in part-time work, with a fall, rather than a rise, in full-time employment rates. There are two exceptions to this generally negative picture. Over the past twenty years the employment profile of men in the Indian and Chinese groups has converged with that of White men. Why these groups, why men and why changes over the period 1991-2011?

Answering questions such as these will help us understand some of the drivers of ethnic inequalities, which are, of course, not restricted to employment but are present in all spheres of life. But the social world and causal processes operating within it are not neat; consider how identities might be configured, experienced, acted upon, reshaped and lived across a lifecourse, generations and periods. This is the challenge of sociology and the social sciences more generally. To deal with complexity, to go beyond common sense, superficial, easy, explanation and to provide understanding without neglecting the complexity of the social world.

James Nazroo is Professor of Sociology and Director of the Cathie Marsh Centre for Census and Survey Research at the University of Manchester. He is also Director of the recently established ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE), which focuses on understanding changing patterns of inequality and identity. Understanding processes of inequality and their relationship to social justice has been the primary focus of his research activities. His work has considered gender, ethnicity, ageing, and the intersections between these. His research on ethnicity is largely concerned with inequalities in health and assessing the contribution that social disadvantage might make to these differences.