Lisa Mckenzie

Dispossession: The Great Social Housing Swindle premieres at 6.30pm, Thursday 15th June at Picture House Central, in London followed by a Q&A. For dates and venues for other screenings, see here.

In A Brief History of Neo–Liberalism, David Harvey argues that within a neo-liberal society accumulation by dispossession becomes essential for capitalism to work. There are four main elements, each of which has major implications for a good and just society. This could not be truer when we think about our most basic human need, a place to shelter. The first element is privatization of public resources and services, which is designed to create new opportunities for capital accumulation in areas once protected from the “calculus of profitability.” Harvey states the following:

The reversion of common property rights won through years of hard class struggle (the right to social goods, welfare, national health care, and pension) into the private domain has been one of the most egregious of all policies of dispossession pursued in the name of neoliberal orthodoxy. All of these processes amount to the transfer of assets from the public and popular realms to the private and class-privileged domains. (p. 53)

Housing has too often been at a cliff edge with regard to social justice and especially with regard to the basic rights of working class families. Without a home, without shelter, a place that can aid safety, stability, as well as comforts, other social goods such as healthcare, education, and rights to justice can never be met. I first started writing about housing twelve years ago when I was researching and writing for my PhD that relied heavily on community studies from the 1950s and 1960s. Bill Silburn and Ken Coates book, Poverty the Forgotten Englishmen (1970), was an important study to me because it was written and researched about a community that I had called home for over 20 years -St Anns in Nottingham. At the heart of this book was housing, and the importance of having a safe, and healthy place that working class people could afford to live in, so their children and their wider communities could thrive.

By 1970, when the book was published, hundreds of thousands of ‘slum housing’ all over the UK was earmarked for demolition. These were predominantly privately owned and privately rented, and hundreds of thousands of new council houses were built to replace the poor housing that working class people in the UK had lived in for generations.

Community studies written from the early 1950’s had been mapping out the importance of housing, homes and communities in Glasgow (Gauldie in 1974) down to the East End of London (Wilmot and Young in 1958) and the Isle of Sheppey in Kent (Pahl in 1984). What these community studies highlighted was that community and neighbourhood was part of a bigger picture of what was happening throughout the UK. That was that the poorest people were not ‘work-shy’, but pitiable low quality housing and depleted wages were at the root of poverty and disadvantage.

Housing became a priority for the UK government, and social policy during this time Community studies researchers, as well as the many grass roots organisations that were highlighting the problems, ensured that the idea of community was at the top of the agenda during what we now call the post-war period 1945-1979. However governments and social policy agendas have tendencies to change their priorities.

As David Harvey argues in his second element of accumulation by dispossession, from the mid 1970s there was an increasing financialisation of economies across the world. In the UK, with the success of Thatcherism came a sharper interest in housing as capital rather than as home. Policy was changed around council housing, which allowed tenants to buy their homes at a reduced price, and then financial deregulation facilitated the redistribution of wealth from workers and productive capital to finance capital through speculation, predation, and fraud.

This story of how housing, homes and community became profit, units, and capital has been told over the years through the academic lens. I have written about the consequences of what happens when community and people are both de-valued simultaneously in my book, Getting By (2015). However I understand that as academics, and as people that understand, write, and speak about social justice we need other forms of ‘storytelling’ that shows what is happening at all levels of society. I was asked by an Independent filmmaker to be involved in a film about council housing, and the swindle that has happened over 40 years in removing housing stock from public ownership and into private hands. Consequently in the UK we are now subject to financial housing bubble, and the worst housing crisis since the 1940s.

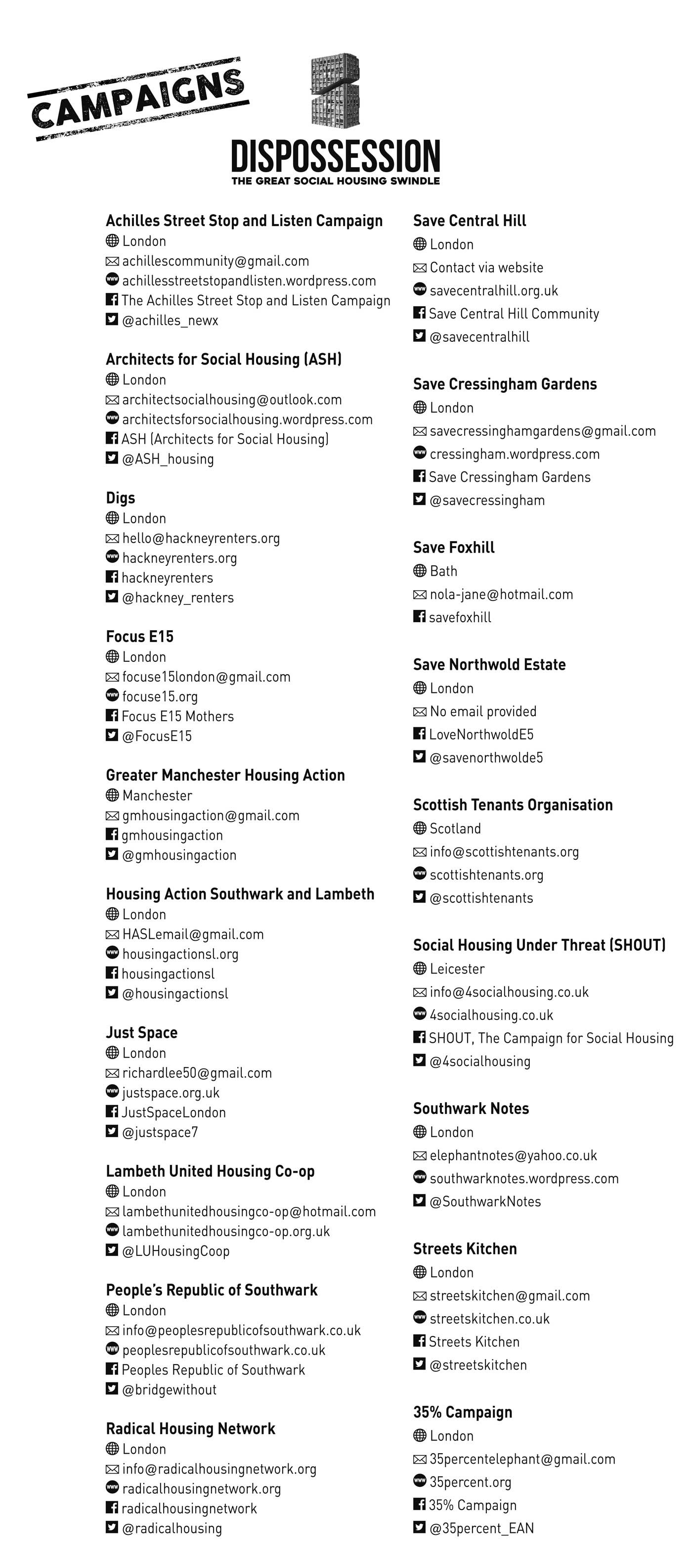

Dispossession: The Great Housing Swindle was partly crowd funded by people currently involved in housing campaigns and by people that believe council housing is an important social good.

The film shows the human side of the housing crisis, giving people who have lost their homes or are in danger of losing them a direct means to tell their stories. But also to encourage others in the same position to organise and campaign to protect their homes and communities. The people featured in Dispossession, politicians, charity workers, and tenants all agree that there is a lack of sufficient council housing. However local councils all over the UK of all political persuasions continue with demolition of council estates, and working with private developers to ‘solve’ the housing crisis.

The film introduces the Aylesbury estate in South London and Beverley Robinson, a resident that doesn’t want to move from her home despite the Labour run council demolishing it around her. Beverley has become a prisoner in her own home, the local council has embattled her in with fences, security guards and razor wire.

The film then introduces the residents from Cressingham Gardens and Central Hill in Lambeth, two other council estates in south London that are earmarked for demolition despite the residents wanting to stay and campaigning desperately to persuade or force Lambeth Council to change their minds. There is very little trust in local councils especially in London that has seen some of the worst gentrification and consequently the social cleansing of poorer residents that follows. The film explains the case of the Heygate estate, also in South London London, that was demolished in 2011. Southwark council worked with Australian property developer Lendlease to demolish the homes of 3000 residents (most whom were council tenants) with an agreement that the estate would be improved and they would have a choice to move back after ‘redevelopment’. However the majority of the tenants were moved away from the Heygate estate to other parts of London, and in some cases out of the City completely. The new development is now complete and of the 2704 new homes built, only 82 are available at social rent.

There are many ways to tell a story, and to show the narratives that weave through society that touch people, that harm people, but also to build confidence and support for social change. I would like to see academics and academia engage in however they can to ensure these narratives are available for all of us, accumulation by dispossession can also relate to knowledge.

Lisa Mckenzie is a research fellow in sociology at the London School of Economics and Political Science.