Lucinda Platt (LSE) and Tina Haux (University of Kent)

How does separation affect a woman’s view of herself as a parent? Our research suggests separation certainly knocks a mother’s confidence and it does not seem to recover quickly over time.

Research on the impact of separation and divorce has tended to focus on its effect on children. We know, for instance, that children whose parents have divorced tend to score lower on a variety of emotional, behavioural, social, health and academic outcomes than children whose parents have stayed married. Children who have experienced a number of family splits tend to have lower academic achievement and higher levels of delinquent behaviour.

But we also know that children don’t show the same level of change if their parents divorce after a marriage where there was a high level of conflict, and that the negative effects of separation can and do improve over time.

There is also some evidence on how a split can affect parents. Separation can have a negative impact on mothers’ income, mental health and life satisfaction. However, the evidence to date has tended to show that, given time, all these recover again, though a woman’s financial health tends to improve more slowly than her sense of wellbeing.

Until now, though, we had less idea of how separation might affect a mother’s view of herself as a mother. Can separation actually affect a woman’s ability to parent?

For the first time, as part of Nuffield Foundation funded research, we have been able to use data from the Millennium Cohort Study (MCS) to explore some of these issues, and to look at whether any impact of separation on perceived parenting competence gets better over time. The MCS is a large-scale survey which follows the lives of children born at or just after the Millennium. Their parents were questioned when they were nine months old and again at three, five, seven and 11 years old. Focusing on the questions asked about parenting ability in the first four surveys we investigated a sample of more than 12,000 mothers, around 2,000 of whom had separated before their child was aged seven.

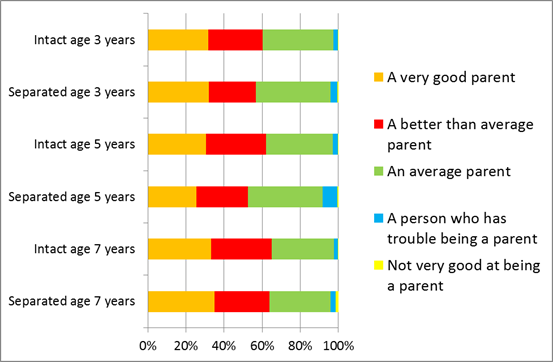

These mothers were asked, pre and post-separation, how they viewed their own competence as parents: did they feel they were very good, better than average, a person who has some trouble being a parent, or not very good at it?

Using recognised question scales we also investigated whether the relationship between separation and parental competence, was linked to changes in a child’s behaviour and his or her mother’s mental health. Looking just at those 2000 mothers who had experienced a separation, we investigated whether evaluation of their parenting competence improved with time since separation, and whether it was greater when parenting was more equally shared, that is when their child spent more time with his or her non-resident father.

What did we find? The results were mixed. Women who separated did indeed suffer a reduced perception of their own parenting competence (Fig 1).

Figure 1: Mothers’ evaluation of their parenting, by separation status and age of child

When we took account of other factors likely to influence parenting confidence, this relationship remained. However, other consequences of separation appeared to explain the knock to parenting competence. Separation went hand in hand with higher rates of maternal depression and with higher rates of child behavioural problems. And these appeared to account for the blow to the mothers’ confidence in their own parenting.

By contrast with other existing research, which suggests that effects of separation tend to recover with time, we found no improvement in perceived parenting competence among these separated mothers as time went by. Mothers who had been separated for longer tended to view their parenting competence in no better light than those who had been separated more recently, even though their mental health did tend to recover.

We also looked at the level of contact between the children in these families and their fathers – could the mother’s view of her own ability to parent be affected by the amount of contact the child had with his or her father? But we found no relationship.

In summary then, separation did affect the perceived parenting capacity of these mothers – but it did so through increased risk of maternal mental ill health and child behavioural problems.

We concluded that these other factors, which were exacerbated by separation, rendered parenting itself more challenging, especially without the presence of the child’s father: that is, that being a single parent is inherently tough. It is, of course, also possible, that the shock of separation may affect a woman’s ability to parent, and that that may have a knock-on effect on a child’s behaviour. But we cannot establish cause and effect here.

From a policy perspective and for those concerned with how best to support families after separation and divorce, it would seem that looking solely for a recovery over time in a mother’s mental health may not be enough to help her get back on her feet after a split. Indeed, if it’s considered important to help single mothers establish a happy, healthy home for herself and her child, then this could give all those concerned pause for thought. Psychological and practical support around parenting are likely to be key.

Tina Haux is Quantitative Lecturer in Criminology/Sociology in the School of Social Policy, Sociology and Social Research at the University of Kent. Lucinda Platt is Professor of Social Policy and Sociologyin the Department of Social Policy at the London School of Economics. This article is based on a Nuffield Foundation funded research project: Parenting and contact before and after separation. Two Working Papers based on the research are published in the LSE Centre for the Analysis of Social Exclusion (CASE) series: Parenting and post-separation contact: what are the links? and Mothers, parenting and the impact of separation. The authors would like to thank their co-author Rachel Rosenberg for her meticulous work in preparing the data and the Nuffield Foundation for funding the study and their continued interest and support for research in this field (the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Foundation).

The research project made use of surveys 1-5 of the Millennium Cohort Study and was accessed from the UK Data Archive. The authors are grateful to The Centre for Longitudinal Studies at UCL Institute of Education for the use of these data and to the UK Data Archive and UK Data Service for making the MCS data available. However, they bear no responsibility for the analysis or interpretation of these data.

Image: Jannik Nitz (CC-BY-2.0)