Elisabeth Becker Topkara (Yale University)

“Keep calm: not a terrorist.” “An eye for an eye leaves the whole world blind.” “#Neveragain.”These are only a few of the signs held by Spanish Muslims at a Madrid rally condemning the Charlie Hebdo attacks in January. Most find violence vile. Still, the prevalence of violence associated with Islam remains high, despite the fact that only a tiny minority of those identifying at Muslims use violence as a means to an ends.

In fact, almost every Muslim I meet during my research in European mosques insists that “Islam means peace.” This line becomes the marker of many repetitive conversations, the words to quickly clarify for me the modern controversies surrounding Islam (most often these days, referencing ISIS)—“I am on your side.” While Islam’s foundational sources most certainly condemn murder and other violent acts, Islam does not mean peace, just as jihad does not mean war. Islam actually means submission (to God). Jihad actually means a spiritual—often internal—struggle to preserve what it means to be Muslim. Still, the associations we make with such specific terms are important, perhaps more important than what lies at their core. Associations define perceptions of who belongs to “us” and who remains always apart as, only “them.”

I hear similar words and see similar struggles in the Muslim communities of the three cities where for 2 years I have carried out ethnographic research— Berlin, Germany, London, UK and Madrid, Spain. Muslim communities are expected to show their stance, if not take a stand, regarding violent strands of, or violent groups identifying with, the religion. Today’s Muslims in Europe grapple desperately with possibilities for purifying the terms of their religion, with semantics linked always to action, with the hope of living their religion on their own terms. The young Muslims leading the aforementioned rally seek to disassociate Islam from images of burning bodies and beheadings, or even from the ‘model migrants’ donning hijabs. They seek to (re)build an image of Islam where we see communities prostrating in beautiful mosques for prayer, the clicking together of small glasses of tea, mothers kissing their children and chiming in to the diverse, dire, intellectual debates of our time.

After two years of ethnographic research in mosques, interviews with Muslim leadership, youth and police, mainstream media analysis and, simply living in Europe, I have seen various tactics utilized by Muslim communities to demonstrate the distance between Islam and violence. Still, most Muslims with whom I speak explain to me that they remain associated with threat. Despite different, creative attempts to draw distance between mainstream Muslims and violent offshoots—many arguing in deep violation of the basic tenets of the religion—European society still perceives these terms as intertwined. Let me put it this way: while Muslim does not mean terrorist, terrorist almost always now means Muslim. The initial response to a plane that crashes into the seas, or to an attack against youth in Norway—such disasters now lead society writ large to interchangeably ask: Was it a Muslim? Was it a terrorist act?

Following the Charlie Hebdo attacks, Muslims in Madrid gathered at the central train station—Atocha—itself symbolically potent as per the Madrid bombings on trains leaving this station in 2005. They attempted to take back this place as a place of peaceful Islamic presence, civil engagement and civility. I was struck by the signs held at the protest condemning the Charlie Hebdo attacks, how simple and to the point they were. How obvious. Most prevalent were numerous pieces of white paper with the words “I am a Muslim not a terrorist” or “Islam=peace” scribbled in handwriting. One held by a young girl read “No violence. The only way out.” And the one bestowing the title of this piece at first made me laugh: “Keep Calm. Not a terrorist.” Yet this sticks in my mind each time I meet yet another young Muslim, who reiterates, “Islam means peace”—those words telling of so much more.

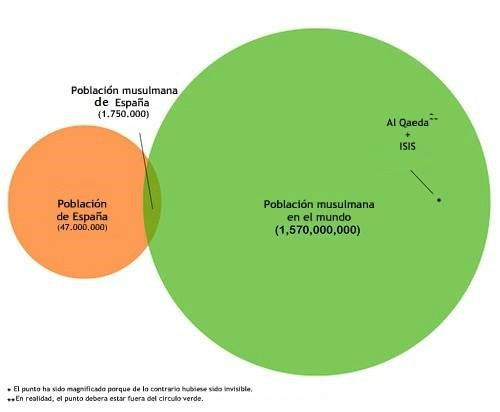

A Spanish journalist with whom I spoke insisted that Spanish society does not take for granted the disassociation of most Muslims from terrorism, rather the leadership must make their stance clear. A diagram (see below) posted on the Facebook page of the

Young Spanish Muslims months after attempts to show the statistical significance of these groups—not as overlapping circles, but with terrorists a small black dot in the huge (and increasing) global Muslim population. The dot remains outside of the circle of Spanish Muslims, suggesting again the desire to distance themselves from this heavy term, to disown this evil step-sister of semantics.

The Sehitlik Mosque in Berlin, my main research site, takes a more aggressive line of action, as it hosts a Violence Prevention hotline, for those fearing their loved ones could be drawn to terrorist groups. Sehitlik cooperates with the Violence Prevention Network, in order to “turn extremists”, knowing that some young Muslims from Germany have (and will) join ISIS. A back room at Sehitlik where I once conducted interviews, once sat with older women bestowing blessings upon my growing pregnant belly, struggling to hold Arabic letters right in my mouth, has been converted into the site of this violence prevention network. Now family members and friends call to discuss preventative measures to be taken against joining the Islamic State, as per the young teens who disappeared from East London in February 2015. This cooperation loudly suggests more than a distancing or distinguishing from violent strands of/associated with the religion and the heavy terms this carries. It suggests the hope to purify local communities from connections to this violent group.

The East London Mosque, my other research site, utilizes different tactics. The head Imam mentions in his Friday sermons that Islam does not condone violence of any form. Following Hebdo, they post a statement: “the East London Mosque would like to offer its sincere condolences to the families of those killed during the #CharlieHebdo attacks. There can be no justification whatsoever for such taking of life.” This mosque community begs back growing numbers of East London teenagers lost to the empty promise of ISIS, to make them honorable brides. Here community members carry other significant signs, as they show solidarity for and with the youth abducted in Nigeria by Boko Haram: “Bring back our girls.” They march not against Hebdo, not against xenophobia, but against the too often forgotten reality that not only the perpetrators we see so often portrayed in the media, but most victims of violent, radical Islam (if you are to call it that) are Muslims.

Elisabeth Becker Topkara is a PhD Candidate in Sociology at Yale University. She is currently based in Berlin, as an NSF, DAAD and MacMillan grantee/Fox Fellow, researching mosque communities in comparative perspective.