John Curtice (University of Strathclyde/ NatCen Social Research)

It is not so long ago that Britain was regarded as a model two-party democracy. Most voters voted for either the Conservatives or Labour and between them those two parties secured almost all of the seats in the House of Commons. As a result – and thanks also to the bonus the single member plurality electoral system typically affords the winner – either the Conservatives or Labour won an overall majority, and consequently who governed Britain was determined by the decisions made by voters, not by deals made by the parties after polling day.

In truth this model has been creaking for quite a while. The share of the vote won by the Conservatives and Labour combined has long been much less than the 97% at which it peaked in 1951. It has not been much above 80% at any time since 1974, while in 2010 the two parties only commanded two out of every three votes cast – fewer than at any time since and including 1922, when Labour first replaced the Liberals as the Conservatives’ principal opponents. Meanwhile, at each of the last four elections, some 80 seats or so have been won by parties other than Conservative or Labour, mostly by the Liberal Democrats but also by Scottish and Welsh nationalists, an assortment of Northern Irish parties and even the occasional representative from other political stables too. Between them these developments inevitably made a hung parliament more likely, which, of course, is precisely what the last election produced, thereby paving the way for Britain’s first coalition since 1945.

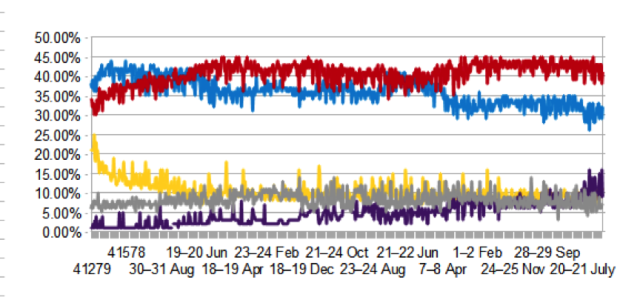

But now it seems the traditional model of British elections faces its biggest challenge yet – despite the fact that voters have reacted badly to the Liberal Democrats’ role in government, with the consequence that the party seems to be heading for it worst result (in terms if votes at least) since 1970. Meanwhile three parties that hitherto have largely played only a minor role in Westminster politics now threaten to achieve record levels of support in May.

First up are UKIP, who achieved remarkable success in the 2013 and 2014 English local elections, came first in last year’s European elections and won two-parliamentary by-elections last autumn. The party’s support has been at or above 10% throughout the last two years. The party has already done enough to claim the mantle of being the most significant wholly independent fourth party challenge in post-war English (sic) politics.

More recent, but no less remarkable, has been an increase in support for the Greens. This first became apparent during the 2014 European elections, a context in which the party regularly does relatively well but after which on this occasion its support continued to grow, reaching some 7-8% of the vote.

Finally, despite failing to persuade a majority of Scots to vote in favour of independence in last autumn’s referendum, SNP is nevertheless riding the crest of a wave. The party has been averaging 45% or more in polls of Westminster voting intentions, enough to put it well ahead of Labour in what was once regarded as their opponents’ fiefdom.

In short, rather than looking like a two, or at most a three-party battle, this election looks more like a six-party contest. Not that the three ‘insurgents’ can simply be lumped together. Each one is drawing on a rather specific wellspring of support. UKIP supporters, for example, are disproportionately older, working class voters who have been attracted to UKIP’s banner above all by a concern about immigration. Socially at least on the right of the political spectrum, they are also disproportionately former Conservative voters.

Green voters are very different. They are typically younger, middle class (often university educated) socially liberal voters who, if they voted for anyone last time around, were most likely to have backed the Liberal Democrats. The party has become a significant competitor to Labour for the support of those who have become disaffected with Nick Clegg’s party.

Meanwhile, those backing the SNP in Scotland consist primarily of those who voted Yes in the referendum and who now appear to wish to affirm their vote in September by backing the party that is the principal standard bearer of the demand for independence. But those who have switched from voting Labour in 2010 to supporting the nationalists also share another characteristic – they are politically on the left, favouring government intervention to create a more equal society, and regard the SNP, not Labour, as the party that is most supportive of that position.

In short, all three ‘insurgent’ parties have been able to mine a particular electoral niche – in a way that smaller parties are often thought to do under systems of proportional representation, but are not expected to be able to do so under single member plurality. As a result rather then a direct battle between Conservative and Labour, the forthcoming election looks more like a set of separate contests between either Conservative or Labour on the one hand and one or more of the ‘insurgents’ on the other. And because the ‘insurgents’ have taken up positions that are clearly either on the left or on the right of the ideological spectrum, this implies that rather than being won or lost on the centre ground, this election will be won by whichever of Conservative or Labour is better able to fend off the challenge they face from those to their right and to their left respectively.

However, when it comes to winning seats, one of these ‘insurgencies’ matters much than the others. In the case of UKIP and the Greens, the single member plurality system looks as though it will be true to its supposed form and not provide either party with very much in the way of representation in the House of Commons. Neither appears to have the geographical concentration of support that a small party needs if it is to turn its votes into substantial numbers of seats. Both parties are likely to matter more for the impact they might have on the ability of others to win seats than for what they themselves are likely to achieve.

The SNP, in contrast, is potentially in a position to win seats, even though at some 5% or so its current share of the UK-wide vote could leave it in sixth place in terms of votes. For unlike the Greens and UKIP, SNP support is, of course, geographically concentrated. At the same time within Scotland itself its vote is actually quite evenly spread – the party is more or less just as popular in Kirkcudbright as it is in Kirkwall – and for a party on 45% or so of the vote that attribute is an advantage. It means the SNP looks as though it is a competitor locally almost everywhere, and certainly potentially capable of winning some 45 or so of Scotland’s 59 seats.

As a result, despite the prospect of a collapse in Liberal Democrat support, the next Parliament looks as though it will once again contain a grand total of some 80 or so MPs elected as something other than a Conservative or a Labour standard bearer. Even if the Liberal Democrats do take a pasting in the ballot box, they could still emerge with some 20-25 seats – these days the party does at least have some pockets of local strength where it can hope to stem an ebbing tide. At the same time, of course, all 18 seats in Northern Ireland will be won by parties other than Conservative or Labour, while Plaid Cymru can be expected to retain their largely Welsh speaking outposts. Between them these various tallies, together with the prospect of some 45 or so SNP seats, takes us to around the 80 seat mark.

As a result winning an overall majority will not be easy for either the Conservatives or Labour. The former are particularly hamstrung by their failure during the last parliament to get the constituency boundaries redrawn and thereby reduce the extent to which Conservative held seats tend to be bigger than Labour held ones. With 41 seats at risk north of the border, Labour are potentially especially badly hit by any substantial SNP success in Scotland. In these circumstances, anything much less than a five point Labour lead or a seven point Conservative one looks likely to result in another hung parliament of one kind or another.

In the event, our politicians adapted remarkably quickly in 2010 to the reality of a hung parliament. But this time, it may not be the Liberal Democrats who, having won approaching a quarter of the UK-wide vote, are handed the role of ‘kingmakers’. Instead it could be politicians from parties in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, parties that between them are supported by fewer than one in ten voters. In that event, the ability to make and unmake governments will seemingly have been transferred from voters into the hands of relatively small parties representing very particular constituencies. That sounds about as far away from the traditional British model of two-party politics as it is possible to be.

John Curtice is Professor of Politics at Strathclyde University and Research Consultant to Nat Cen/ScotCen Social Research. He conduct research into social and political attitudes, electoral behaviour, electoral systems and survey research methods in Scotland, Britain and comparatively. He is President of the British Polling Council, a body that maintains standards of disclosure by political polling organisations. He has been a co-editor of the annual British Social Attitudes reports since 1994 and co-director of the Scottish Social Attitudes surveys since their inauguration in 1999.