Charlie Jeffery, University of Edinburgh

Scotland votes Yes or No to the question ‘should Scotland be an independent country?’ on 18 September 2014. That seems straightforward enough – except that it is not yet entirely clear what ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ really mean.

What the Yes camp means by ‘Yes’

The Yes camp is dominated by the Scottish National Party, which forms a majority government in Scotland and is by far the biggest component of the official pro-independence campaign, Yes Scotland. We now know much more about what the Yes camp thinks Yes means following the publication of the Scottish Government’s mammoth White Paper, Scotland’s Future, in November 2013. The White Paper marks out the terrain of independence in three ways.

The first is to set out a fairly select number of areas in which an independent Scotland would be markedly different to a Scotland within the UK. The aim is to pose tough challenges to the claim that, as the official No campaign’s title puts it, we are ‘better together’ with the rest of the UK. Here the messages are simple:

- We will get the governments we vote for (aka no more Conservative-led UK Governments with weak representation in Scotland)

- No more ‘bedroom tax’ (as the headline message of a wider theme about a sense of fairness and social justice the Scottish Government thinks can’t be delivered through UK institutions)

- Comprehensive pre-school childcare (presented in terms of equality of opportunity both for children, and in relation to women’s participation in the labour market)

- Confidence in the role of the state in defining and delivering public services (the headline bogey issue here is the UK Government’s privatisation of the Royal Mail)

- No nuclear weapons.

Second there are areas in which the Scottish Government would not do things so much differently than the rest of the UK, but rather argues that it could do those things better if Scotland were an independent state. The most obvious area here is an economic policy which would not be wildly different in the balance of market and state or in nurturing key economic sectors; the argument is rather that economic policy would be better attuned to Scottish circumstances and less led by the gravitational pull of London and the South East of England if Scotland were independent.

And then there are areas in which the same things would happen in much the same way. The most obvious example is on currency. Scotland would share in a formal sterling currency union involving a common central Bank of England, with a common monetary policy, common financial services regulation and fiscal coordination on debt and deficits, the latter placing limits around Scotland’s fiscal autonomy. But there are plenty more examples of other continuities and of services that would be shared between an independent Scotland and the rest of the UK, such as a continuing common travel area (meaning no physical border would be needed between Scotland and the rest of the UK), a common research area for university research funding, and reciprocal arrangements between a new Scottish Broadcasting Service and the BBC so everyone would still be able to watch Eastenders.

This conception of what Nicola McEwen has called ‘embedded independence’, an independent statehood embedded in continuing partnerships with the rest of the UK, has many echoes with equivalent conceptions of independence in other places with strong pro-independence parties like Catalonia, the Basque Country and Quebec. In each of these cases the mainstream proponents of independence argue that independence is about recalibrating rather than ending (or ‘separating’) relationships with the residual state. This aspect of what the Yes camp means by ‘Yes’ has become the core terrain of the referendum debate.

What the No camp means by ‘Yes’

Logically enough such notions of independence amid continuing partnership require a willing partner in order to be realised. This is where the meaning of ‘Yes’, should Scotland vote that way in September, becomes unclear because the No camp appears unwilling to consider such a partnership.

The No camp has two main components: the UK Government and the three pro-union parties – Labour, the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats – which are (somewhat uncomfortably) partners in the Better Together campaign.

The UK Government has responded to the challenge of the referendum by producing a series of Scotland Analysis papers (likely thirteen or fourteen of them by the time they finish) of even greater collective length than the Scottish Government’s White Paper. The Scotland Analysis series has several papers on economic issues, but covers also EU and international relations, defence and security, university research, borders and migration, and welfare. The core argument is that the status quo is in all these policy fields a better option than independence and gives the ‘best of both worlds’ to a Scotland with a powerful devolved Parliament and continued access to the scale and strength of the UK as a whole.

The Scotland Analysis series has regularly engaged with the idea of independence-as-partnership, generally giving a message that there would be no guarantees that the partnership arrangements foreseen by the Scottish Government would be ones a residual UK would wish to enter into. That message hardened with the publication of the Scotland Analysis paper on currency union in February 2014.

The currency union paper presented a stark analysis that a formal currency union would not be in the rest of the UK’s interest. It was accompanied publication of the advice of the Permanent Secretary to the Treasury, Sir Nick MacPherson (and unusual move), that currency union was not in the UK’s interest, and closely coordinated speeches by George Osborne as Conservative Chancellor of the Exchequer, Danny Alexander as Liberal Democrat Chief Secretary to the Treasury, and Ed Balls as Labour Shadow Chancellor reiterated a common mantra: ‘It is not going to happen’.

Much of Osborne et al’s justification while couched in the language of economics was really much more about hard ball politics. This coordinated strike was an attempt to blow a hole in the Scottish Government’s vision for many aspects of independence – not just the economic ones – as a continuing partnership between two independent states using many of the same institutions, like the Bank of England, which currently provide services for the UK as a single state.

The message to the Yes camp appears to be: if you really want to have independence, then it won’t be ‘embedded’ independence but (for want of a better phrase) ‘real’ or ‘classical’ independence with an independent currency and all that goes with it. Similarly there have been hints about the need for a physical border (especially if an independent Scotland were to have a different immigration policy than the rest of the UK), the ending of a common research area for university research funding, and even the denial of the BBC’s programming (and, we presume that would mean no more Eastenders) to the Scots.

What the No camp means by ‘No’

This toughened up line led by the UK Government on what Yes means has been accompanied by a softening of the line on what No means by other parts of the No camp. Over the last couple of years proposals have accumulated from pro-union parties and think tanks on various forms of further-reaching devolution that might be offered to Scotland in the event of a No vote.

First out of the blocks was the ‘Devo-Plus’ group which emerged in the orbit of the Scottish centre-right think tank Reform Scotland in May 2012 with the first of now three reports setting out in turn a vision of greater tax devolution for Scotland, some devolution of welfare policy, and a commitment to the constitutional entrenchment of the Scottish Parliament (so that it could not be dissolved by the UK parliament as it can at present). The Liberal Democrats followed in October 2012 with the report of their Home Rule and Community Rule Commission. This covered much of the same ground as Devo-Plus, adding to it a commitment to strengthen local government in Scotland.

Then came the London-based, Labour-leaning think tank the Institute for Public Policy Research with its ‘Devo-More’ project which has set out, in two reports in January 2013 and March 2014, its own schemes of tax devolution and devolution in welfare policy.

Both the Labour Party and the Conservative Party set up commissions during 2013 to explore further-reaching devolution. The Conservatives are set to report in May 2014. Labour’s Devolution Commission published its final report in March 2014. This again echoed many of the proposals of the other pro-union/more devolution voices, offering more strengthening of local government than the Liberal Democrats, less welfare devolution than Devo-Plus or IPPR, and a commitment to the constitutional entrenchment of the Scottish Parliament.

Labour’s Commission,– most strikingly – set out by some way the least far-reaching of all of the pro-union schemes for tax devolution and, (under the strong influence of former Prime Minister Gordon Brown) the strongest articulation of all of the purposes and benefits of what it called ‘the sharing union’. So while the other tax devolution schemes propose somewhere between 55 per cent and two-thirds of the Scottish Parliament’s spending being covered by its own tax revenues, Labour’s Commission set a ceiling of 40 per cent.

And it did that as a second step in a process which first specified that 60 per cent of the Scottish Parliament’s spending needed to be funded by transfers from Westminster of tax revenues generated by the UK-wide taxpayer. This is intended to make concrete the idea of shared purposes (in part described in the language of social and economic rights) by pooling resources across the union.

With that the Labour Commission’s proposals place by some way the strictest limits on future devolution. It may well be that they end up as the least devo-enthusiastic of all the main pro-union forces when the Conservatives’ Commission reports in May 2014.

The Median Voter: Neither Yes nor No

Labour’s position is important as it is both the main competitor to the SNP in the Scottish Parliament and the party at Westminster most dependent for its prospects there on the size of its contingent of Scottish MPs. This tension between electoral logics in Scotland and at Westminster explains the relative modesty of its Commission’s proposals, which are a compromise between devolution-sceptics (largely among Labour MPs at Westminster) and devo-enthusiasts in Scotland.

Is that compromise enough to encourage a strong No vote? Insight into that question is available in what we know of constitutional preferences in Scotland. The referendum in September offers a binary choice: Yes or No. Voters’ opinions about Scotland’s constitutional future do not map onto this binary choice. Opinion is split three ways between the status quo, fuller devolution, and independence. This can be illustrated with data from the Scottish Social Attitudes Survey, as in the table below.

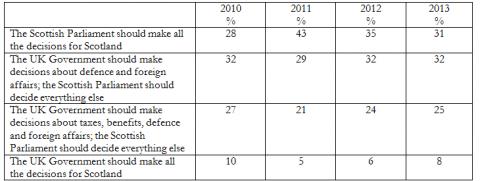

Who Should Decide What?

Source: Scottish Social Attitudes (2014), The Score at Half Time: Trends in Support for Independence.

The first row in the table describes Scottish independence. The second – where the Scottish Parliament ‘should decide everything’ except defence and foreign affairs (but including taxes and welfare benefits) – is an approximation to what has become known in shorthand as ‘devo-max’, or maximal devolution while remaining in the UK. The third broadly describes the status quo, and the last the situation that existed before devolution. While there is some year-to-year churn it is clear that the status quo is supported by only around a quarter of Scots and the repeal of devolution altogether by at best one in ten.

There is a clear majority in public opinion for a constitutional situation beyond the status quo. This majority is more or less evenly split between independence and devo-max. And there is a clear majority for staying in the union if all the non-independence options are added together.

As the two sides in the debate develop their referendum strategies it is clear that the devo-max group is the key group (the ‘median voter’ in political science language) needed to make a majority either for a UK Government focused on the merits of the status quo or a Scottish Government seeking Scottish independence.

The views of the median voter explain the strategies on both sides of the debate. The Scottish Government’s vision of independence-as-partnership is intended to signal reassurance, through institutional continuity, that independence would not be a leap in the dark. In that way it hopes to open out support from hard-core pro-independence supporters into the devo-max grouping.

The UK Government’s insistence on ‘real’ independence in the event of a Yes vote is intended to make independence appear as stark, difficult and risky as possible, limiting its appeal to the hard core and deterring devo-maxers from supporting it. Equally the proposals on further-reaching devolution by Labour and the rest are intended open out the No vote into devo-max territory.

The challenge on the Yes side as the referendum approaches is to keep credible the vision of independence-as-partnership in the face of the UK Government’s firm insistence on ‘real’ independence and its denial of the prospect of partnership. The challenge on the No side is to render credible the idea that sufficient additional devolution will be offered to sate the appetite of the median voter group, and then delivered by some combination of pro-union parties in the event of a No vote. The Scottish public appears not to be fully convinced this would be the case.

Neither side appears to be on very secure ground. In other words, there is still all to play for!

Charlie Jeffery is Professor of Politics at and Vice Principal, University of Edinburgh and Director of the ESRC Programme on The Future of The UK and Scotland. He has co-ordinated this Issue of Discover Society featuring research from the Programme.