Christina Boswell, University of Edinburgh

While the UK Home Office continues to pursue its target for reducing net migration, north of the border the debate is more focused on how Scotland can increase net migration. According to the Scottish Government, the country has quite distinct labour migration needs compared to the rest of the UK. With a more rapidly ageing population, Scotland will be increasingly dependent on immigration to offset dependency rates and fill labour shortages. Current arrangements, it is argued, are hampering Scotland in realising these immigration goals. But how realistic are prospects for increasing immigration to Scotland, and are the SNP Government’s plans workable?

Can Scotland Attract the Immigrants It Wants?

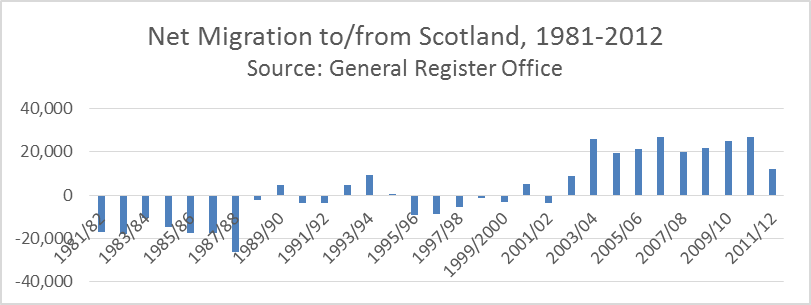

Scotland has been concerned about decreasing fertility rates and population decline since the 1960s. Indeed, the Scottish Government has argued that the country would need to sustain annual net migration of around 17-18,000 per year to meet its population growth target. More recently, the SNP has been less outspoken about this idea of large-scale replacement migration, instead emphasising the need for more selective recruitment of highly skilled migrants. But it remains committed to the idea of immigration as an important tool for boosting its population, and for offsetting its rising dependency rate (the ratio of economically active to inactive population). While this demographic trend is not unusual across Europe, Scotland is projected to experience a more rapidly rising dependency rate than other parts of the UK.

Projected Population Structure for Scotland/UK (Office of National Statistics)

Sustaining such high levels of net migration was not a problem in the 2000s, when Scotland saw net migration of around 20-25,000 around this period. The UK as a whole was admitting a higher number of migrants – partly through the Labour government’s expansion of opportunities for labour migration – in the context of a booming economy and acute shortages in many sectors. Scotland received a generous share of these immigrants.

Would Scotland be able to sustain this level of net migration in the event of independence? The Scottish Government has argued that it is being held back from attracting more immigrants because of the restrictive policies pursued by the Westminster Government, which is aiming to radically reduce levels of net migration to the UK. Yet immigration policy is not the only determinant of migration flows. Economic context matters too. Levels of immigration to Scotland and the UK stabilized in around 2007/8, coinciding with the financial crisis and onset of recession. It is difficult to compete for (especially skilled) labour migration in the absence of a buoyant economy. Moreover, the substantial increase in EU immigration after 2004 was in some senses unique: only the UK, Ireland and Sweden opened their labour markets to new EU members in 2004, giving them a head start in attracting immigrants from Central Europe. Now the UK needs to compete with the likes of Germany, France, Spain and Italy to attract migrants from new member countries.

The upshot is that restrictive UK immigration policy is not the sole – or arguably the major – reason for a decline in net migration to Scotland. There are a number of economic and geo-political factors that helped Scotland achieve such a dramatic increase in immigration in the 2000s. If an independent Scotland were to see a period of growth and increasing labour shortages, then we might expect it to become a popular destination once more – especially for those keen to migrate to an English speaking destination. Here, Scotland could benefit from the fact that the rest of the UK is signalling that EEA migrants are not welcome. It could also benefit from the networks of Central European migrants already established here.

However, it is also quite likely that in order to meet population targets, Scotland would in fact need to recruit quite substantial numbers of low-skilled, non-EEA immigrants. This in turn might create challenges in garnering public support for immigration.

Will the Scottish Public Support a More Liberal Policy?

Immigration is clearly a very salient and contested issue in the UK right now. A number of commentators, however, have suggested that Scotland is different: Scots are generally more tolerant of immigration than their counterparts in the rest of the UK.

How far is this born out in recent surveys? If we look at the latest British Social Attitudes survey, we can see some differences. For example, on the question of whether immigration should be reduced or increased, 78% of English and 69% of Scottish respondents say it should be reduced. Differences in views on the impacts of immigration are less pronounced. 46% of English and 44% of Scots think that immigration has a negative economic impact. While 44% of English and 40% of Scots think it has a negative cultural impact.

Arguably, though, immigration issues are not as salient in Scotland as in the rest of the UK. A recent BBC poll ranked immigration as the 7th most important issue for voters in the Scottish referendum. By comparison, immigration regularly comes in as one of the top three issues of concern to UK voters.

It is worth noting in this respect that none of the three main Scottish political parties have mobilized on an anti-immigration platform. But we should be cautious in the conclusions we draw from that. There may well be an untapped demand for more restrictive rhetoric and policies. And in the event of independence, there are likely to be greater incentives to mobilize support around immigration issues. The Scottish government would for the first time be held to account for immigration policy. In turn, the media would be likely to become more critical of government policy. And there would be increased incentives for opposition parties to whip up public concerns about a more liberal policy. We have seen this pattern across Europe, with immigration becoming one of the major issues of party political contestation in immigrant-receiving countries.

How Autonomous Would Scottish Immigration Policy Be?

Here we come to our third feasibility question. Let’s assume, as most commentators appear to be doing, that Scotland is admitted to the Common Travel Area (CTA) between the UK, Ireland, the Isle of Mann and the Channel Islands. In principle, members of the CTA have full autonomy over their immigration and asylum policies. In practice, Irish immigration policy is fairly well aligned with that of the UK. Like the UK, it saw a considerable rise in immigration in the first part of the 2000s, with a decline the past 6 years. But that has more to do with Ireland’s economic situation than any constraint exerted by the CTA.

Now the UK government has argued that a more liberal immigration policy in Scotland would necessitate the introduction of border controls with rUK. How likely is this scenario?

The SNP has suggested it would adopt a more humane asylum policy. Now one scenario is that this might lead to increased numbers of asylum applications. Note that Ireland saw a 100-fold increase in the late 1990s/early 2000s – such fluctuations can occur. Such an increase would likely trigger concerns that asylum seekers – and especially those whose applications had been rejected – might travel on to places where they could find work, or to join family and kin. And that might imply taking advantage of the absence of border controls and moving southwards, to reside and work on an irregular basis. This has certainly been a headache for Schengen countries, who have been concerned about irregular movement from southern to northern European countries. It would not take large numbers of irregular migrants moving across the border to raise alarms in London. In the event of such flows being picked up by the media, it would put a rUK government under pressure to demonstrate it was being tough, and may well lead to talk of introducing border controls. While it is likely such measures would be ad hoc and largely symbolic, such a response might in turn exert pressure on the Scottish Government to introduce more restrictive measures.

An independent Scottish government would technically be free to adopt a more liberal immigration policy. But it would be unlikely to adopt a significantly different approach to that of the UK. One reason for this would be the need to respond to rUK concerns about the control of irregular migration. But just as importantly, an independent Scotland would likely struggle to attract large numbers of highly skilled and/or A-8 migrants, certainly at the level required by its population target. And it would face challenges garnering public support to admit large numbers of low-skilled non-EEA migrants. Much as pro-immigration commentators might wish it were otherwise, it is unlikely that Scotland would be willing or able to adopt a markedly more liberal immigration policy.

Christina Boswell is Professor of Politics at the University of Edinburgh. She has written extensively on UK and European immigration and asylum policy, including Migration and Mobility in the EU (with Andrew Geddes, Palgrave 2011) and The Political Uses of Expert Knowledge: Immigration and Social Research (Cambridge, 2009).