Gita Hashemi

Between 2015 and 2016, I engaged in a two-part performance project entitled Declarations in order to examine the contemporary conditions in which notions of the universality of human rights are contradicted structurally as a matter of daily reality. In the first part, travelling from Canada to Germany, through the Balkans and Turkey, I focused on the right to freedom of movement. The second part took shape in Palestine and focused on the right to land.

Drawing ley lines across three continents (and many centuries), Declarations allowed me to explore the resonance of my specific history, as a displaced person from Iran, with the contemporary spaces I inhabit and those that I passed through over the course of the project. Ley lines are hypothetical lines that connect places of significance, and are believed to carry special energy. I invite you to join me as I re-trace these lines:

A Hunk of Clay

Embedded in Iranian national identity is the notion that Cyrus the Great instituted the first universal declaration of human rights. Iranian jurists and politicians constructed this narrative to put Iran on the international stage and protect its sovereignty against Western expansionism during and after WWII. Their efforts culminated in the first international conference on human rights held in Tehran in 1968, and the enshrinement at the UN Headquarters of a replica of the Cyrus Cylinder, said to contain the first declaration of universal human rights. Therein are displayed the contradictions that still undermine notions of universal rights.

Inscribed in cuneiform in 539 BCE, the clay cylinder’s text was written to mark the military conquest of Babylon, a significant stage in the expansion of an empire at an unprecedented scale. The rights were granted by a king, whose authority came from God, to his subjects, defining relations of power between the state and its subjects: pray to what god you will, and keep paying taxes, and, in the case of conquered nations, tribute to the central government.

Today, we well know that because rights are to be guaranteed by the state, they are inevitably subject to power and politics. In that first human rights conference in Tehran, the actual practices of the Pahlavi monarchy – a repressive regime buoyed by the USA – were not questioned.

The cylinder was toured in Iran and the US between 2010 and 2014, accompanied by a big fanfare, meant to normalize Iran’s international presence and relationships. Iranian and American personalities posed with the cylinder for the media. At a ceremony in Iran, then-president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, during whose tenure women’s rights activists were repeatedly subjected to street beatings and mass arrests, spoke of how the cylinder emphasised “freedom of thought” and “respect for human beings’ greatness and basic rights.” Ahmadinejad then put a chafiyeh, a symbol of the Palestinian nation, around the neck of a bearded actor posing as Cyrus, perhaps to counter that other fabricated – and challenged – narrative according to which Cyrus liberated the Jews from captivity in Babylon and allowed them to return to Jerusalem.

Declarations I: On the Move

Underneath all the posturing about human rights, every day, in the ways in which migrants and refugees are produced and subsequently treated by nation-states, “universal” human rights are trampled upon. Exploring the right to freedom of movement, in part one of my project I undertook a pilgrimage along one “refugee route” in Europe. I made the journey in reverse, starting from two “destination countries,” Germany and then Austria. I then traveled the “Balkan route,” passing through Croatia, Hungary, Serbia, Macedonia, and Greece, all considered “stepping stones,” and I ended in Izmir, Turkey, a main “port of departure.”

Throughout the journey, at every stop, I connected with people who were on the move toward a place of safety, and benefited from various forms of hospitality extended by local activists and artists who supported freedom of movement. I worked with them to create occasions and spaces, mostly involving food, where those on the move were re-positioned as hosts and the locals became guests. I also volunteered as an interpreter and helped local activists in other ways. I raised funds for all this by selling mailart that partially documented, with permission, the stories of people I met along the way. Although I don’t have space to include these stories here, they were all important, all filled with hope and despair, displaying tenacity in the face of adversity.

The space of this work became a tenuous link, an energetic and spiritual line, that connected the various people I had relationships with through the journey, including those who bought my missives, people on the move, and activists and artists who believed in the right to freedom of movement. This link was activated in the context of many different forms of hostility.

Europe opened in 2015 to the first wave of refugees only – those who had more money, higher education, and better connections. Before the EU’s Dublin Agreement in February 2016, Frontex, border guards and militias were already operationalized for push back using fences, beatings and shootings. After Dublin, even the UNHCR became a push back instrument. While traffickers still operated freely, activists faced criminal charges as traffickers.

There were also forms of individual and group hostility and microaggression both within people on the move and among activists. All the familiar prejudices were at play, sometimes exaggerated under extremely stressful conditions. But, simultaneously, the space was permeated with hospitality and co-operation, generosity and empathy.

Specially, when we came together over food, there was joy and curiosity, the stuff that transform tenuous links into lasting bonds. Temporary reversal of the roles of guests and hosts allowed for an energetic shift that echoed a not-too-distant history when Europe’s refugees found hospitality in much of the “Middle East.”

Declarations II: On the Land

Motivated by expansionism, settler states violate the rights of Indigenous peoples, causing massive displacement and ravaging the land and all its inhabitants. This can be seen most readily in Israel, where seventy-plus years of terrorising state policies and settlement practices have created one of the largest and longest displacements of people post WWII, and a deeply scarred landscape.

Focusing on the interconnectedness of humans with the land and all beings, and the rights of all to thrive in peace, part two of my project took shape through the hospitality of Dar al-Kalima University in Bethlehem, where I was an artist in residence for four weeks. There, I hosted performance workshops for 4th-year visual arts students.

To examine their own connections to the land, we examined the effects of state violence, occupation and war on the people and on the land itself as a live and responsive habitat. Tapping into their family histories, the students interviewed and recorded their parents and grandparents telling stories about their 1948 or 1967 displacement. We also explored Palestinian traditions that centre on relationships to land, including family picnics and walks in the hills, both now heavily encumbered by the military occupation and land fragmentation. We then took to explore the land itself, and landed at Al-Makhrour.

Declared a world heritage site and considered one of the most significant sites of bio-diversity in Palestine, Wadi (valley) Al-Makhrour is an agricultural area covered with 3000-year-old terraces on rolling hills, demonstrating Palestinians’ harmonious stewardship of land and water, passed from one generation to another. Al-Makhrour is in Palestine proper, but is designated as Area C, meaning that it is under Israeli military control. It is overlooked from atop the hills on one side by one of the largest illegal Israeli settlements, Har Gilo; and Israeli forces repeatedly enter the valley to destroy Palestinian buildings. Although Al-Makhrour is still heavily cultivated with fruit and olive trees by Palestinians, and it is a beautiful site easily accessible from Bethlehem, the students either had not visited it or did not consider it a hospitable area.

On May 15 (Nakbah day), 2016, while in Bethlehem people staged protests at sites where the occupation wall cut through the city, the students reclaimed their connection to the land by hosting a walk through Al-Makhrour. We started in Battir village where Mazin Qumsiyeh, the director of the Palestine Museum of Natural History and Biodiversity, talked about Al-Makhrour’s history, and the significance of its unique flora and fauna. Then the students, Alaa Attoun, Manal Awad, Mohamad Mostafa, Balqees Othman and Varvara Razaq, took turns leading the procession toward Beit Jala in silence while we played back the voices of their parents and grandparents retelling their memories of displacement. The procession climaxed with a collective, and radically cathartic, scream toward the settlement across the valley, followed by spontaneous singing of folk songs and dancing of dabke.

Declarations started from an inquiry into a national myth, and took meaning from where and when it unfolded as it unfolded. As an art project, it had a strong social practice character, where the production of any art object was only peripheral. The main objects here were concepts and relationships that animated the social space in which notions and practices of rights and universality played out in everyday reality. People entered the space of this project as participants and collaborators – rather than spectators; – and brought their ethos and pathos to the midst. Over the course of the journey, the challenge became to manifest processes, spaces and structures that could engender empowerment and, perhaps, healing, while negotiating between hostility and hospitality.

Gita Hashemi is an award-winning artist, curator and writer whose experimental transmedia practice centers on marginalized histories and contemporary politics, and explores social relations, language and the imaginary. Originally from Shiraz, Iran, and now based in Canada. Two of her most recent projects, Emergent and Dreams Reload, include podcasts that are in free distribution. She is currently working on Archive Iran: Encounters with a Century, a multi-part, multi-platform project that foregrounds women’s agency in the 20th Century Iran, and The Woman I Want, a performance based on the writings of the early-twentieth-century radical feminist, Zandokht Shirazi. For years she has been saying “The personal is poetic, the poetic is political, the political is personal.” Sometimes she tweets at @gitaha

Photos and artwork from the Declarations project are available for purchase with proceeds going toward aiding Syrian refugees in Turkey and Lebanon. Contact info@subversivepress.org

Image Credits:

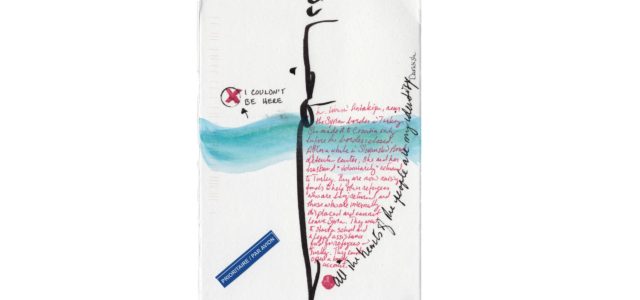

Image 1: Caption: Gita Hashemi, The Line of the Road, from the mail art series, Notes from Here (2026), courtesy of the artist.

Image 2: Caption: Gita Hashemi, Tabanovce Refugee Detention Camp, from the photo series, Nth Movement, Enduring Transience (2016), courtesy of the artist.

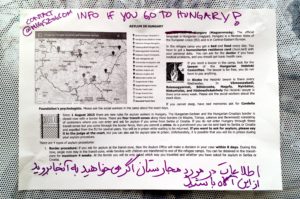

Image 3: Caption: An information flyer posted by Migszol activist at the bus station in Sabotica, on the Serbian side of the border with Hungary, March, 2016. Photo copyright: Gita Hashemi.

Image 4: Caption: Illegal Har Gilo settlement atop the far hill overlooking Palestinian lands in Al-Makhrour. (2016) Photo copyright: Gita Hashemi.

Image 5: Caption: Gita Hashemi, On the Land (2016), performance procession through Wadi Al-Makhrour. Photo copyright: Saleh Zighari.