Jim Rogers

I am concerned for my 91 year old mother. Which son or daughter is not concerned at the moment for the welfare of an elderly parent? We know that so far at least 12,526 people have died from COVID 19 in UK care homes, 27.3% of all deaths of care home residents. My mother has had several stays in care homes in recent years, following falls and fractures. She remains living independently, with domiciliary care visits. At the start of the crisis I was worried about care staff being vectors of transmission for the virus, and cancelled most of those care visits, to take on the role myself. As an academic working from home and isolating, and living less than one mile away, I took the view, rightly or wrongly, that this would be a safer option. Today, 21st May, the CQC reports on COVID19 deaths in recipients of home care and on staff sickness due to COVID19 in the home care staff population.

There are actually three groups of older vulnerable individuals for whom we should be particularly concerned: those living in care homes,those receiving care at home, and those in need but not receiving any care. Social care has been the poor relation to health care in the UK for decades. Underfunded and fragmented whilst facing increasing demand, the result has been that all three of those groups have been growing in number and need, whilst the level of support has generally decreased.Numerous reports and government enquiries have resulted only in the issue being filed under too expensive and too difficult to solve and effectively kicked into the long grass.

The COVID 19 crisis has brought into sharp relief a number of existing social inequalities and some of the inequities in social care have been particularly brought to the fore. The sector was very fragile before any of the current difficulties. Local authorities had over the last few years reported companies handing back contracts or going out of business, and service users reporting difficulties in finding the care they need. All of these issues have been exacerbated during the crisis.

There has been belated recognition of the problems facing care homes in relation to COVID 19; homes in which 418,000 individuals reside. This is 4% of the total population aged 65 years and over, and 15% of those aged 85 plus.167,000 people are receiving dementia care in care homes – around 40% of the total care home population.The care homes issue has now made headlines and dominated prime ministers questions but there has been silence until now in relation to home care.

350,000 older people in England were estimated to use home care services in 2015, 257,000 of whom had their care paid for by their local authority. Accurate information about this care is hard to come by, because of the complexity of the ‘care’ landscape. Multiple providers, different funding arrangements and an unknown amount of unregulated care, particularly for non personal care such as shopping and cleaning, all add to the challenge of understanding this sector.There are thought to be almost 10,000 different agencies providing home care. Since the Care Act 2014 there has been an increasing emphasis on personalisation and many people now employ their own personal assistant, although increasingly these arrangements are brokered via agencies.

The amount and type of care required varies considerably but a person with the poorest health and the greatest need may the one receiving the most frequent visits, and also be most vulnerable to picking up infections. Some individuals receive four visits per day and during these visits carers may be providing intimate personal care with close contact inevitable. As the comedian Rhod Gilbert found when he worked in this role for his Work Experience programme, this work is difficult, challenging, highly valued by those in receipt of it, and highly undervalued by society in terms of recognition and remuneration.

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) are responsible for regulating social care providers, both in relation to care homes and to home care. In April CQC wrote to home care providers asking them to update CQC every week day on the impact of coronavirus using an online form.The latest data shows that between 10th April and 8th May there were 3161 deaths in users of home care services. 553 of these took place whilst the home care user was in hospital but the majority took place at the users home (1664) or the location was not stated. Of that total number of deaths, 593 were recorded as COVID related, or almost one in five, and most agencies reported cases.

Unsurprisingly most of the COVID19 fatalities in users of home care occurred whilst the individual was in hospital (334 of the 553) and only 10% of the deaths that occurred actually in users homes were registered as related to COVID19. Presumably home care users who do become seriously ill with coronavirus will make their carers aware of the situation and are likely to be referred or taken to hospital.

We have heard a lot about how many NHS staff have contracted and died from the virus, and there have been tragic and widely publicised cases of dedicated hospital staff paying the price for continuing to work in the face of high risks.But what of the dedicated army of care staff who work for minimal pay, facing the same risks, with arguably even less access to adequate PPE? Some care homes have locked down to the point of staff living on the premises or in caravans outside. Such measures are not possible when your role requires you to visit fifteen different service users in the same number different locations on a given day.

Problems with the supply of PPE have been well documented in relation to the NHS. Home care staff support many individuals across the course of their shift, often visiting the same people on multiple occasions, which leads to an increased need to change PPE more regularly.New guidance from Public Health England now states that face masks and eye protection should be worn continuously until the care worker needs to remove them to eat or drink, or to take a break.The government has also outlined the technical specifications that PPE must meet before they are used. But the UK Home Care Association said home care providers are experiencing difficulties in obtaining face masks which meet these specifications and have been in daily contact with the DHSC about the issue

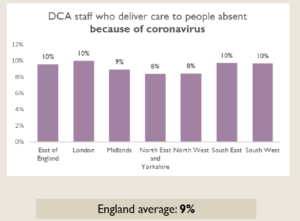

We now know that in most areas almost 10% of Domiciliary care agency (DCA) staff are reporting sickness absence due to COVID-19, which confirms my hunch in February that this population were sadly very likely to become highly exposed and in turn to become spreaders of the virus.

A further concern relates to those who are in need but are not in receipt of care. With the steady reduction in the proportion of the population deemed eligible for social care, there is now a huge cohort, estimated at 1.4 million people by the CQC, who were not receiving the care and support they need even before this pandemic. These people are likely to be more socially-isolated than ever before.

A further concern relates to those who are in need but are not in receipt of care. With the steady reduction in the proportion of the population deemed eligible for social care, there is now a huge cohort, estimated at 1.4 million people by the CQC, who were not receiving the care and support they need even before this pandemic. These people are likely to be more socially-isolated than ever before.

Perhaps some of the responses to the pandemic can also offer some lessons for the days ahead, when there are finally some overdue reforms to social care. Many are arguing that social care should be ‘brought into’ the NHS, in order to integrate both funding and service structures. But as the Kings Fund notes, this brings some risks, and the kind of flexible and personalised care and support which is often valued by service users is not the kind of prescriptive medicalised care, organised by large centralised bureaucracy, which the NHS has been good at.

To assist during the crisis, a nationally administered NHS volunteer scheme was launched to great fanfare in March and there was much congratulation that 750,000 individuals offered their services in response. By the end of April this army of willing folk had been offered a total of only 20,000 tasks, with many signing on for hundreds of hours and being offered nothing to do. In contrast many local initiatives have sprung up in which people recognised a local need and got on with meeting it, quickly organising and mobilising support via social media. By March over 200 community support groups had already emerged in the UK and many more have developed since. This shows that volunteering, and support for those in need is much in evidence in our communities. The only caveat to this is that such support is patchy and is perhaps more in evidence in areas which have existing higher levels of social capital, leaving a risk that geographical and other inequalities are reinforced.

It is to be hoped that all of those in my mother’s generation get the support that they need and deserve. This crisis has illustrated more clearly though that without urgent reforms to the organisation and funding of social care, those without family or community support will be at great risk of remaining alone with their needs.

Jim Rogers is a senior lecturer at the University of Lincoln. He teaches on a range of social work and other professional programmes and conducts research on mental capacity, various other aspects of social care, and also on gambling related harm.