Lisa Kalayji

On 26th January, 2020, Kobe Bryant, the storied American basketball player, was killed in a helicopter crash in the Los Angeles area, along with one of his daughters and seven other people. He was 41 years old. The untimely and violent loss of this much-beloved sporting figure sent shock waves of grief into the professional basketball community, the Los Angeles area that considered Bryant one of its own, and of course his surviving family and friends. Responses, however, were mixed, as many remembered a less laudable aspect of his comparatively short life: his alleged rape of a 19-year-old hotel employee in Colorado in 2003. (Bryant was charged with felony sexual assault, but after being subject to the intimidation and abuse commonly directed at women who accuse public figures of sexual assault, the alleged victim decided not to testify in court and the charges were dropped. She later settled with Bryant in a civil case that included a non-disclosure agreement.)

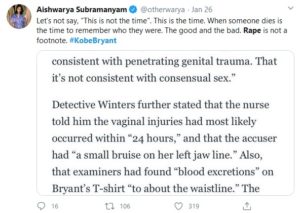

The reignition of this controversy almost immediately following the news of Bryant’s death brought on a parallel public debate about what it is appropriate to say, and when. Renewed attention to the alleged assault came as a shock to many who consider it taken for granted that ‘one should not speak ill of the dead’ (or at least not the recently dead), as well as those who would simply prefer that sexual assault survivors and their advocates be kept out of public discourse. Some public figures and organisations, however, remained adamant that it is never the wrong time to acknowledge sexual violence, nor ever the right time to protect (alleged) perpetrators’ reputations:

Others were eager to point out that sexual violence perpetrators are already extended the advantage of a collective amnesia enforced through the harassment of survivors and their advocates:

Some private individuals* responded with still more fervour, characterizing Bryant as a rapist and an adulterer, bemoaning his post-mortem valorisation, and in some cases professing to be glad that he had died.

These polarised responses offer an opportunity – and perhaps highlight an obligation – for us to collectively re-evaluate our conceptions of what constitutes justice following a sexual assault. Framings of sexual violence perpetrators and survivors are imbricated with heavily racialised and gendered social structures and discourses. They are constituted within partially distinct but deeply entangled frameworks: (1) the violent patriarchal control of women’s bodies and subjectivities, and (2) state apparatuses of ‘criminal’ ‘justice’ which, in contexts like Bryant’s home of the US, function largely to reproduce a racial caste order that elides blackness with criminality.

There are urgent questions to be asked, therefore, about who ultimately benefits from each possible approach to justice, as well as about what ‘doing justice’ actually means. Should sexual violence be handled through retributive or restorative models of justice? And what does restorative justice in such a circumstance look like? What might it have looked like in this particular case?

Rape Culture & the Figure of the Vindictive Rape Victim

On the face of it, incorporating ‘don’t mourn a rapist’ and ‘I’m glad he died’ narratives into Kobe Bryant’s public post-mortem seems like an unambiguous stand for the dignity of survivors. With systematic disbelieving and silencing of assault survivors (most of whom, not by coincidence, are women) being established as one of the defining features of hegemonic patriarchy, to demand that rapes not be conveniently forgotten is a political corrective.

These rightly angry declarations, however, do more discursive work than immediately meets the eye. An assumption implicit within them is that to treat the death of a rapist as tragic would be a betrayal of his victim. Striking down Bryant’s sterling image thereby becomes a symbolic defence of the woman who has greatly suffered, and may continue to suffer, from her encounter with him in 2003. She is The Rape Victim, and it is for her sake that (pro-)feminist people must not regard Bryant’s death as a sad or unfortunate event.

What does this suggest about collective conceptions of rape survivors? A spectral figure seems to undergird this form of victim advocacy who, I would argue, is incompatible with a feminist cultural politic. She is vengeant and spiteful, harbouring malice and resentment, living in hope that her assailant gets his due – and then celebrating when he does. She must, it is assumed, have been glad to hear that he plummeted to his death with his adolescent daughter in tow, and those who publicly express precisely this sentiment are merely nodding in agreement with the spectre of the victim. The ghosts of women persecuted as ‘witches’ haunt these discourses: the witch lusts for revenge on those who have somehow scorned her, hoping to inflict suffering and possibly premature death. She is a splinter in the cohesion of a community that must be cast out (and indeed this is scarcely a metaphor, with contemporary public rape accusers being cast out through harassment, rape threats, and death threats). What begin as gestures of emotional solidarity, then, can unwittingly invoke and reproduce a deeply patriarchal imaginary.

Bryant’s alleged victim has not publicly commented on his death, and no one is in a position to speculate about how she may feel about it. Indeed, rage, which can include a desire for the perpetrator to suffer as the victim has suffered, is a normal psychic response to interpersonal violence traumas such as rape, and can be a legitimate part of the healing process which ought not be condemned or subjected to moralising evaluations. If that is what Bryant’s victim has felt or is feeling, she cannot be justifiably reproached for it, and anyone who has either experienced or directly witnessed the extreme emotional (and often physical) injuries left in the wake of a rape will understand why. The invocation of her assumed feelings on the part of her defenders, however, may have some unintended consequences. Firstly, it makes the sustenance of that trauma-induced rage a feminist imperative, and by extension, it frames healing, understanding (which is not to say excusing), and reconciliation as failures – as bad feminism. Secondly, and relatedly, it makes restorative justice, in which the survivor and their wider community demand and receive accountability and harm-repairing work from the perpetrator with a view to restoring ruptured interpersonal and community relationships, impossible. In other words, it requires that a ‘good’ or ‘righteous’ rape survivor crave the sort of retributive response that is enacted by states through policing, the judicial system, and incarceration.

The Racial Politics of Rape Culture

This brings us to the elephant in the room. It is a tale as old as European colonialism: white women pitted against black men. Following on from a history of upper-class white men enslaving black men and women and keeping white women as de facto property (otherwise termed ‘wives’), black men have come to be culturally constructed as the threat to white men’s dominance par excellence. Their assumed hyper-physicality, inscribed through white colonialists’ own dehumanisation of them, incites white men’s fears of losing of all of their ill-gotten property, and their manhoods with it (1).

The contemporary legacies of this organisation of power lead to violence and coercion which quickly lay bare whose interests are really served by retributive models of justice. Middle- and upper-class white women are subject to possessive control of their sexualities by class-elite white men and their expressions of power through the state: the suppression of sex education, the restriction of access to contraception and abortion, and a cultural double-bind which demands that white women be both chaste and perpetually sexually available to – and this is crucial – only worthy suitors, which is to say middle- and upper-class white men themselves (special exceptions can sometimes be made for wealthy or highly accomplished men of colour, who are accorded honorary whiteness).

Women of colour, and black women most especially, are systematically excluded from material power, ensuring that they can be exploited in ways that clearly echo patterns established during black enslavement: disproportionately barred from access to both wealth and reproductive rights, they are forced to reproduce a workforce mostly destined for entrapment in low-wage work, for the profit of capital owners who will then frame them as hyper-sexual welfare scroungers (this, in turn, paves the way for them to be sexually assaulted at staggering rates and with impunity) (2). Black men, whose hyper-physicality and hyper-virility are figments of the white imagination, are come down upon as the viable threat to the dominant power order that they are taken to be: criminalised and incarcerated at extremely high rates and for inflated periods of time, routinely murdered by the state (even, sometimes, as children who never live to become men at all), and rendered in hegemonic caricature as monsters from whom white women must be protected (the sexual assault of white women is, of course, tolerated, as long as it is perpetrated by class-privileged white men).

Expressions of righteous anger are foreclosed to all of the above (black men most especially, who express anger only at their mortal peril), ensuring the maintenance of a moral logic in which class-elite white men maintain a monopoly on legitimate claims to injury and its redress. That redress is delivered through the violence of powerful, and powerfully legitimated, institutions: the judicial and carceral systems, migration and border enforcement authorities, legislative decision-making bodies, and medical institutions that pathologise what cannot be openly punished while conferring differential treatment along gendered and racialised lines.

What, therefore, are the knock-on costs to white women, women of colour, and men of colour when retributive conceptions of justice are relied upon to heal the wounds of sexual violence survivors, and to prevent the perpetration of similar horrors in the future? What does a just world – one free of sexual violence, of racism, and of the accumulation and abuse of power in general – look like, and how can our responses to sexual assaults integrate that vision?

The Emotional Politics of Time

Of course any discussion of how we respond must incorporate the related question of when we respond. Media outlets began broadcasting news of the helicopter crash before the families of the people killed could be notified. Outpourings of feeling from the public were quick to follow. In a recklessly impatient media landscape that incorporates emotional vampirism into its business models, there is no time for the stages of grief, or the stages of most anything else. There is a lot of money to be made in accelerating the pace of public dialogue, and those capital interests collide with an already taut tug-of-war between feminist and anti-feminist discourses. Precisely because many people inevitably rushed to reflect upon Bryant’s remarkable life, it was necessary for feminists to leap in to prevent yet another sexual assault from being erased from the historical record (their concerns were not unfounded – in spite of the well-publicised rape allegations, Bryant received a BET Sportsman of the Year Award in 2008, an ESPY Icon Award in 2016, and an Academy Award in 2018, amongst other accolades).

This tension creates a seemingly unwinnable situation for all involved (except, of course, media conglomerates’ shareholders). To do sexual violence survivors justice requires that perpetrators not be shielded from accountability, including reputational damage, because ‘it’s not the right time’ (it is never, after all, the right time to be raped, either). However, a feverish rush to the keyboards to prevent the complete erasure of histories of violence is unlikely to yield a public conversation that will either address survivors’ needs or advance the creation of a world where less sexual violence occurs. An impoverished political imagination might be left stymied by this false dilemma, but a radical rethinking of the meaning of justice itself opens up possibilities that entrapment in capitalist and carceral logics forecloses.

What Repairs a Sexual Assault?

So what would a reparative justice response to all of this have looked like? If Kobe Bryant had responded reparatively, this would have included listening to and bearing witness to his victim if she wanted that (free of the intimidating gaze of attorneys whose purpose was to indemnify the accused perpetrator), listening to and witnessing other survivors, undertaking feminist therapeutic work to understand and redress the entanglement of misogyny with his masculinity and sense of self, and a commitment to bystander intervention in other incidents of sexual violence, harassment, or misogynistic talk amongst men. Perhaps most crucially, he would have unconditionally acknowledged the reality of the assault and the full scale of the harm it did the victim – a gesture which, under present structural conditions, would have landed him in prison (a forceful deterrent if ever there was one).

All of these measures would have been discussed on an ongoing basis with his local community of survivors and their (chosen) advocates, who would have held him accountable to the ongoing process of repair. As Bryant was a prominent public figure, he would also have needed to use his public platform to encourage healthier forms of masculinity and respect for women’s agency – with power comes responsibility, and he had a kind of power that not everyone who sexually assaults someone has. The survivor of the assault would need to be granted unfettered access to all of the support she might need, including time away from work and other responsibilities to focus on recovery, physical and mental health support from appropriately trained specialist clinicians, and an open invitation to demand witnessing from and dialogue with the perpetrator if she decided she wanted it.

What is Reparative Justice After a Perpetrator’s Death?

Of course, none of that happened, which left the ledger of justice indefinitely imbalanced. There remain, however, options available to salvage some measure of justice in what has been a profoundly unjust situation. That might begin with an agreement amongst the community of people affected on a timeline for reparative work to be undertaken. The families of those killed in the crash would ideally have been notified of the accident before the media publicised it, and a reasonable amount of time allotted (a few months, maybe?) for people to grieve and come to terms with the loss, with the understanding that sexual violence survivors are entitled to a public conversation about Bryant’s past action, and that this is non-optional and should be respected when the time comes to have it. This case could then be used as an opening for having conversations – and making demands – about what a just response to sexual violence looks like, and for strategising concrete ways of implementing that justice in practise.

Reparative justice does not require that rape survivors, whose psyches have been fractured by terror and trauma, be sympathetic or compassionate to rapists – their own or other people’s. Nor, however, does the perpetrator’s suffering or premature death (i.e., punishment) have to be part of doing survivors justice. Indeed, the perpetrator’s suffering doesn’t mitigate the survivor’s at all. Only justice – being heard, believed, witnessed, supported unconditionally through the healing process, and seeing the assailant held accountable – can do that. Perhaps one of the most difficult aspects of doing reparative justice after sexual violence in communities, and especially in functionally global communities that link survivors across vast distances through their shared witnessing of a famed case like Bryant’s, is that many survivors will re-live their own traumas by the experience of witnessing the aftermath of someone else’s. The foremost claim to justice in any case of sexual violence nevertheless belongs to the survivor of that assault. What this means in practise (or in praxis?) is that the wider community of survivors must have the unfettered access that they themselves need to process their own emotions, but likewise that they must not superimpose those on the survivor of the case in hand, or speak on her behalf.

Maybe the survivor of Bryant’s assault did feel some amount of righteous satisfaction at his death. Maybe she found it terribly sad. Maybe she felt a bit of both. Regardless of what her feelings actually were, if we are committed to ending rape culture and creating a world in which rapes happen much less, in which assailants are held accountable when assaults do occur, and in which the genuine healing that can only come from truly just responses is the rule rather than the exception, then the mythic figure of the Vindictive Survivor must be banished from our cultural imaginaries, and with it, the figure of the hyper-sexual, hyper-aggressive black man.

A retributive and legislative model of justice in which moral wrongness is equated with illegality (and rightness with legality), and in which the carriage of justice takes the form of punishment, ensures the reproduction of a scaffolding of structural racism which doubly harms women who are sexually assaulted: it reifies the legitimacy of state and (white) men’s control of women’s bodies, and it re-inscribes criminality onto blackness, placing black women even further from justice when they are assaulted (especially by white perpetrators). The imperative to continue working during the aftermath of an assault is an invisibilised violence which illustrates the entanglement of patriarchy and capitalism, and demonstrates the need to free workers from labour for profit so that their energies can be directed toward taking care of themselves and each other.

The endeavour to create a world in which rape is, if not wholly a thing of the past, at least an uncommon aberration, requires nothing less than a full-scale revolution: a wholesale supplanting of profit and property with reordered processes of production and exchange oriented to the fulfillment of needs, holistic well-being, and sustainability, the negotiation and delivery of full reparations for the ongoing material and cultural legacies of colonialism in all of its forms, the abolition of policing, surveillance, retributive justice, and prisons, radical transformations in relationship networks and communities of accountability, and the extension of fully recognised personhood to all people, reflected in both discourse and practise.

*Private individuals are un-named and their comments paraphrased for their safety and privacy.

References

(1) Fanon, F. (2017[1967]) Black Skin, White Masks. London: Pluto Press.

(2) Collins, P.H. (2000[1980]) Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment, Second Edition. London & New York: Routledge.

Lisa Kalayji is an independent sociologist of emotions, culture, and social in/equalities at Organization Cultures and co-convenor of the British Sociological Association Emotions Study Group. Twitter: @LisaKalayji Website: www.organization-cultures.com

Image Credit: Maureen Barlin