Ala’a Shehabi and Mai Abu Moghli

As the days roll on, like soup, and the future is foggy, the perpetual present is a struggle between stagnation, continuity and change. We have all the time, and no time at all. Our mortality stares us in the face, yet it is so distant if we just wash our hands and stay at home. We are in control but have no control at all. In this endless present where days seep into each other, when will tomorrow arrive? We are waiting for a tomorrow that is yet to come. Futurity has a horizon, we once knew what that horizon was, we no longer do. We do not know how or when this pandemic will go away, until then, we wait.

It is a liminal condition of time and space that Western theorists are yet to define – it will surely keep them preoccupied for many years to come. ‘Global public intellectuals’ are attempting to do so in the moment; Agamben, Esposito, Zizek etc invoking bare life, or biopolitics and to continue to universalise old theoretical principles – falls short of a condition that is yet to be fully understood and one that must be de-centred epistemically from a Western context. It lacks an authentic engagement and understanding of a pandemic as a mutually constitutive global condition.

Others are busy making a theory of why we need theory. Is theory not a luxury borne of the privilege of time and space. And whose theory actually counts? Are we confusing musings and anecdotes with theory? Is there an epistemic necessity to think about our condition and to rationalise the new and the strange here and now? These attempts are trying to remind us what the role of the intellectual is in this pandemic, it represents an epistemic crisis not an ideological one as yet, about what it is we as scholars are to do, and who are we to become.

There are few historic references in terms of scale and consequences in recent memory. Historians are busy digging up archives from the Spanish Flu in 1918 for a possible reference on the impact of lockdowns. References to the second world war (WW2) or 9/11 fall short in comparative terms even if the discourse of war, battles, and enemies when speaking about the virus prevails.

What would triumph look like, what does defeat look like when people are being buried in mass graves in parks and body bags have run out. War analogies, especially the frequent reference to WW2 fall short in many respects, both morally and as a lived experience. In this global upheaval, there is much to be learnt from the experiences of others, on the margins and the peripheries.

There are other contexts and situations where humans have been living under conditions of forced lockdowns for much longer and it is a surprise that few in the Western Academy have made the link. We have been in lockdown at the time of writing for over a month. The occupation of Palestine since 1948 to take one such example, has produced much thinking on lockdowns. Particularly on the state of waiting, or the concept of ‘waithood’ used to describe the condition of being in situations of protracted displacement – where refugees are suspended, or trapped for long periods of time in encampments within Palestine itself and outside it.

Ruba Salih argues the refugee camp is the most potent embodiment of this condition of ‘waithood’ where the refugee life acquires an ontological quality of waiting for sovereign life. “In a time of waithood, merely waiting for their re-insertion into a national order of things,” Salih says. It has also been used to describe the condition of youth unemployment and the loss of livelihood opportunities.

This limbo, is the liminal space where time has been suspended, it is an affective state, but it can also be a politically potent one, one that forecloses hope and disempowers. A future with no temporal horizon creates the tension of being able to imagine everything, to dream of a beyond and a reality that forces us to imagine nothing at all.

Many Palestinians have been in refugee camps since 1948 with no foreseeable return in sight. Many Palestinians live under extended curfews and under siege. Many Palestinian and Arab political prisoners serve administrative sentences, suspended in limbo. The “C” in collective and community is what connects the experience of lockdowns here with the current pandemic. Palestinians however are effectively in a lockdown within a lockdown. Mariam Barghouti has been writing posts and tweets with the hashtag #Covid_19MeetsOccupation.

Waiting can at once be thought of as disempowering and anxiety-inducing, but it can also be an important coping mechanism for hope, that tomorrow will one day arrive. We are not used to waiting, we therefore do not like it. Others have waited for much longer.

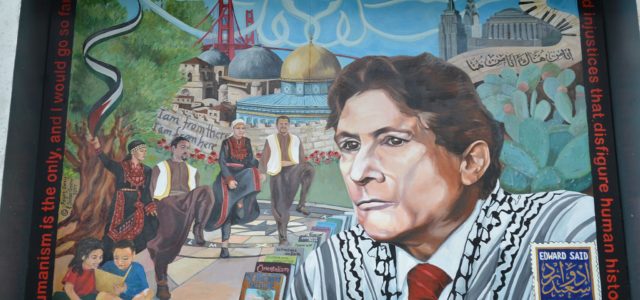

Palestinian intellectual thought both diasporic and under occupation also spawned what we now know to be critical theory and postcolonial thought. Edward Said’s (1996, 2002) work on theories of exile might be useful in thinking about the affective dimensions of lockdowns and ‘social distancing’ from a more extreme condition of military occupation.

To be forcibly removed from your family and community is to be an exile within your own country, to dream of your mother’s bread and coffee (to quote the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish). As we reconcile with exile within our own homes, we must de-exceptionalize it. But Said understood exile to also be an ontological condition.

Exile, he says, ‘is the condition that characterizes the intellectual as someone who is a marginal figure outside the comforts of privilege, power, being-at-homeness’ (1996: 53). Many of us know very little about epidemiology, virology, or public health, we sat aside watching for weeks – as exiles, questioning the relevance of our research in the process of re-thinking it.

Linking the affective with the political is extremely powerful in this state of temporal disruption. Lockdowns as a governance tool have had profound implications on our personal lives, but it is only in a crisis that moments of political change occur, as Stuart Hall said ‘every crisis is also a moment of reconstruction’ referring to the oft-cited Gramscian idea of interregnum: the period between the decay of an old social order and the birthing of a new one. And what is the role of the intellectual in all this?

While in the West this is still debated, African academics have a much clearer idea: they have mobilised, including Achille Mbembe who theorised the very apt idea of necropolitics (the power to decide who lives and who dies) in a letter: “We call upon on all African intellectuals, researchers from all disciplines and the dynamic forces of our countries to join the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic, to enlighten us with their thoughts and talents, to enrich us with the fruits of their research and with their constructive proposals. We must set an optimistic course, while being courageously aware of the gaps that need to be filled.”

The current condition invites academics to leave the luxury of deterministic disciplinary certainties and to sit in this feeling of exile and loss, torment and entrapment, to learn to live with it in order to fulfil the embodied role of an intellectual. More importantly, it invites us to use it as a lens into the lives of those living under lockdown under longer and much worse conditions than this, to centre the marginalised, the ignored, and as Arundhati Roy says, ‘the deliberately silenced’.

Intellectuals like Edward Said long ago specifically wrote about the role of the intellectual in times of crisis, as Palestinian scholars and now our African brothers and sisters have mobilized, it is time for the Western academy to catch up.

References

Said, Edward W. 1996. Representations of the Intellectual (New York: Vintage).

Said, Edward W. 2002. “Traveling Theory Reconsidered,” in Reflections on Exile and Other Essays (Cambridge: Harvard University Press).

Ala’a Shehabi is the Deputy Director of the Institute for Global Prosperity (IGP) and the Data Manager for the RELIEF Centre. Mai Abu Moghli is a Research Associate at the Institute of Education-UCL, her work focuses on Education in Refugee Contexts.

Image Credit: Briantrejo / CC BY-SA