Max Weedon

Reflecting on the recent UK general election and the reasons for a Conservative majority, I am drawn to the role played by epistemic violence and the damage this aspect of the ‘war’ against critical thinking does to democratic processes. In her text ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’ Gayatri Spivak (1) used the term ‘epistemic violence’ to describe the colonial style silencing of marginalised groups such as the ‘illiterate peasantry’, ‘general non-specialists’ and the ‘lowest sub-strata of the urban proletariat’. Epistemic violence in these terms privileges the epistemic practices of those holding power and influence, whilst dismissing the ‘provincial’ knowledge of this underclass.

I argue below that we live in times where the underclass in western societies can also be considered subaltern in that their voices are often dismissed, undervalued or derided by an increasingly authoritarian field of power. Likewise, epistemic violence is used against people like Jeremy Corbyn, who may be perceived as a threat to the neoliberal project currently dominating the field of power.

We can see this epistemic violence in the recent UK general election, which, from my perspective, was an election that was won by the Conservative Party for two main reasons. Firstly, the Remain friendly position adopted by Labour, and secondly the unrelenting smear campaign against Corbyn. After Corbyn helped to point Labour’s compass into an anti-neoliberal direction he faced the wrath of the field of power. The media aligned with the Conservative Party and the Blairite right of the Labour party to castigate Corbyn. A report published by the LSE calculated that between 15 and 20 per cent of the Corbyn-related coverage in The Daily Telegraph, The Daily Express and The Sun associated Corbyn with the IRA, Iran, Hamas, Hezbollah and/or terrorism and overall found that 75% of press coverage misrepresented Jeremy Corbyn, concluding that ‘what emerged is an overall picture of most UK newspapers systematically vilifying the leader of the biggest opposition party, assassinating his character, ridiculing his personality and delegitimising his ideas and politics’.

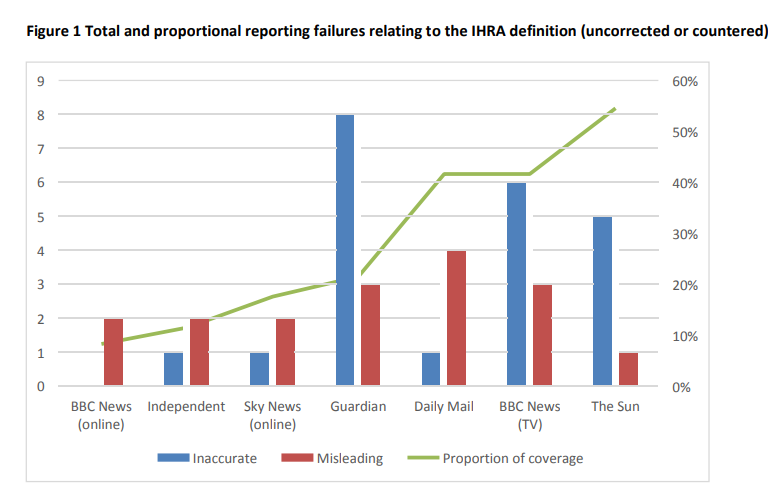

In ‘Labour, Antisemitism and the News: A disinformation paradigm‘, Justin Schlosberg and Laura Laker found ‘prevalent errors, omissions and skews in the mainstream coverage’ in the fever pitch reporting on antisemitism in the Labour Party amid claims that the Labour party had become ‘institutionally racist’ under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn, and that the prospect of a Corbyn-led government posed an ‘existential threat’ to Jewish life in Britain. Interestingly for those on the Left, the Guardian beat even the Daily Mail to include the largest percentage of inaccurate statements on antisemitism to Labour’s disadvantage (see fig. 1 below).

Fig 1. Schlosberg & Laker

In terms of Brexit, the UK newspaper coverage before the EU Referendum overwhelmingly backed Brexit and despite warnings the Remainer response too often veered to fear and abuse. Epistemic violence was in my view epitomised on BBC’s Politics Live when the author Will Self said: “You don’t have to be a racist or anti-Semite to vote for Brexit, it’s just that every racist and anti-Semite in the country did.” After the referendum certain elements among the Remainer faction characterised Brexit voters as an uneducated, economically illiterate and racist underclass or peasantry, victims of education apartheid and poverty, with the implication, despite evidence to the contrary, that their stupidity meant they were easily influenced and swayed from the ‘sensible’ choice to vote remain by ‘fake news’, their minds hijacked by politically opportunist populists, by Russian interference and by adverts on a bus. All of these things were judged to have swayed Brexit voters over and above their own empirical experiential knowledge of life in the EU, and their perceptions of the EU as a whole. After the referendum the losing Remainers in the Labour party mobilised to overturn the referendum result culminating in a manifesto committed to a second referendum which many have said contributed significantly to a Conservative majority in the Houses of Parliament, and paradoxically has resulted in an increased likelihood of Brexit taking place.

Wielding this epistemic violence has arguably become counter-productive in that it forces people into ‘echo chambers’ and ‘safe spaces’ where opposing views are not heard, challenged, debated and forged anew. Perhaps most importantly by dismissing the views we experience epistemological failure. We fail to understand the potential legitimacy of the views. We fail to explore the often valuable perspectives in the marginal discourse. By delegitimizing the viewpoints we may in fact reinforce them, and we miss an opportunity to help fix the underlying problems that they represent. Worryingly the progressive left seem as prone to this kind of authoritarianism as the far right. In the case of Brexit the progressive left failed to counter the media bias towards Brexit.

Pre election, former White House chief strategist Steve Bannon set an interesting trap for the progressive left in a speech to the right wing French National Front. His wide ranging speech was widely characterized and dismissed by the mainstream media with the following racist sounding soundbite: Steve Bannon: ‘Let them call you racist… Wear it as a badge of honor’. In the articles underneath these headlines the journalists would often expand the quote to include a little more context, for example ABC included a fuller version of Bannon’s quote: “Let them call you racist. Let them call you xenophobes. Let them call you nativists, wear it as a badge of honor. Because every day, we get stronger and they get weaker.” Scary stuff, and if we just use such secondary sources to understand what Bannon said we would assume he was a far right racist. However, if we risk losing social capital by using primary research techniques, and listen to his (hard to find) speech in its entirety we see how Bannon sprung his trap.

A more comprehensive quote from the full speech is as follows: ‘why do they call you racists, and xenophobes, and nativists, and homophobes, and Islamophobes, and misogynists? Because they can’t answer the basic questions that you put in front of them. You argue for sovereignty and they call you a nativist. You argue for your freedom and they call you a xenophobe. You argue for your country and they call you a racist. But the days of that smear are over… the globalists have no answers to freedom, let them call you racist, let them call you xenophobes, let them call you nativist, wear it as a badge of honour’. The full context is that Bannon is saying that when the media smears rather than confronts an argument head on that they have lost the ability to win the argument. That the media, with some exceptions, generally choose to smear Bannon rather than analyse what he was saying proved his point, further undermines an already distrusted fourth estate.

What is it we don’t hear? Bannon’s full speeches are more complicated than we think. He tends to heavily criticize central banks and central governments, he speaks of the ‘crisis’ of capitalism, rejects ethnonationalism, criticises the fourth estate and the ‘Davos propaganda machine’, he speaks of tearing down ‘crony capitalism’ and in certain cases he rails against aspects of globalism that harm the working classes in western nations undergoing the structural adjustments of late capitalism. It is these kinds of arguments that unite these highly unlikely bedfellows in critiquing aspects of the neoliberal project; Steve Bannon on the right and Jeremy Corbyn on the left. What also unites this strange pairing is suffering the same kind of epistemic violence faced by Brexit voters, by Trump voters and by the Gilets jaunes etc. An epistemic violence that obscures their discourse and smears them as antisemitic in Corbyn’s case, as far right in Bannon’s case, and as ‘typical’ French malcontents in the case of the Gilets jaunes, in the rare instances that what could be considered to be the epoch-defining 21st century French Revolution even breaks through the almost pathological silence observed by the UK intelligentsia.

Instead of facilitating the public’s engagement and empathy with different positions on complex issues such as Brexit, the fourth estate too often serves up a crude soap opera, with groups such as Brexit voters, the Gilets Jaunes and Trump’s base too often being othered, dismissed, castigated or ignored by a crisis ridden fourth estate that has a highly concentrated ownership of billionaires. Voices from across the political spectrum such as Jeremy Corbyn and Steve Bannon that dare to criticise the neoliberal project, or to claim to speak up for the underclasses are smeared, labelled far right, or far left, or racist etc., and their nuanced views suffer misrecognition, become mischaracterised, and are too rarely challenged. Thus, their arguments become taboo and off limits by association. To our homogenizing safe spaces and our social media echo chambers we retreat, safe from hearing and processing the views that challenge our narratives, avoiding Socratic debate and dialectical reasoning, avoiding empathy and understanding, and therefore unable to confront their arguments and views head to head and win (or lose) the debate. Divided into camps we perceive the other side as an enemy and unfortunately what seems to go missing is genuine empathy for the other’s position and a rational debate of the ideas. Epistemic violence leads to epistemic failure.

Institutional sociology understands the social universe as a collection of distinct institutional logics or fields. For democracy to work the fourth estate needs to hold power accountable. To do this effectively it needs to be distinct from other fields, protected from undue influence from the economic field and the security field. Does the media as it is currently structured fulfil the democratic role of a fourth estate? It would appear the public in the UK and the US are losing faith.

According to the Independent Press Standards Organization newspapers are obliged to ‘make a clear distinction between comment, conjecture and fact’, so let’s hold them to it. And let’s take less heed of secondary sources. Instead of allowing journalists to frame the debate and control the narrative we need to use primary sources to make up our own minds, and we need to research the areas that are silenced. Nothing should be taboo or off limits. Epistemic violence should not cow the academy. When we see epistemic violence obscuring what people say it should be a red flag. Brexit voters, Trump supporters and the Gilets jaunes etc. need empathy and understanding, because if we allow their voices to be silenced then we all suffer epistemic violence, because we fail to learn and we remain divided. As Kant said: sapere aude, dare to know (2).

Notes:

(1) Spivak, G.C. and Riach, G., 2016. Can the subaltern speak? (p. 254). London: Macat International Limited.

(2) Kant, I., 2019. Answering the question: What is enlightenment? Strelbytskyy Multimedia Publishing.

Max Weedon was born in Botswana and is a doctoral researcher of education at the University of the West of England. He is a full time music & film lecturer in England. Having previously co-founded an African children’s charity for HIV orphans, taught in primary education, designed curriculum in the FE & HE sectors and been a governor in the HE sector.

Image Credit: Maggie Zhan