Miriam Snellgrove

In September 2019 the 44th World Bridge Team Championships took place in Wuhan, China. Players from all over the world engaged in a tournament that lasted fourteen days and was avidly watched by amateur players and bridge enthusiasts online as well as in person. To say that competitive bridge playing is taken seriously would be an understatement. For many people it is more than a hobby, it is a serious mind sport with all its own personalities, dramas and moments of tense and challenging play.

But what does it mean to take bridge seriously as an academic field of study? How is bridge seen within an academic institution where ideas of ‘serious’ work and study are often ubiquitously connected to crime, drug use, social inequalities and deprivation (to name a few). In such a setting how do researchers position their work on bridge as academically rigorous and deserving of equal attention and merit? Based on my own reflections of joining the Keep Bridge Alive research team, I explore what it means to be taken ‘seriously’ as a bridge researcher and what this tells us about knowledge production as an ongoing and contested process. I will also offer some tentative thoughts on how bridge as a four-player card game could be taken seriously by people beyond academia (and the bridge community) and what bridge has to offer us in these increasingly politically fragmented, lonely and socially divided times.

To start, I want to share a situation that has regularly occurred since academic colleagues discovered I was working on bridge. This vignette is important as it reveals a certain disdain for the study and credibility of bridge and also, though politely expressed, for the people who research it.

Academic: So what are you working on now?

Me: Bridge.

Academic: As in Bridges? Things civil engineers build?

Me: No, the card game bridge.

Academic: Hmm and that is sociological how exactly?

Me: In lots of ways that we are currently exploring.

Academic: (unconvinced but laughing) Next time my students complain about how boring penal reform is, I’ll tell them – you could always be studying bridge.

It is important to stress here that laughter and puzzlement are often the abiding responses I have received not just from academic colleagues but also from family and friends. I do not think if I had told them I was researching chess, poker or the online world of gaming I would have received the same response. Why is that? What is it about bridge that causes amusement and laughter rather than the usual ‘oh so interesting/have you read x, y or z.’ There is clearly something about the current cultural status of bridge more broadly and certainly within academia, that excludes it from immediately being given the label ‘serious’ research.

In her work on women’s roller derby, Maddie Breeze (2015) discovered something similar. Whilst bridge and roller derby are both recognised as ‘sports’ by official sports governing bodies and played by professionals who are paid (varying sums to do so), the battle regarding academic seriousness is one they share. To be fair it is not just the fact that they claim the label ‘sport’ in ways not conventionally understood, but the label ‘seriousness’ is also connected to older, more established hierarchies of knowledge within academia, that bridge and roller derby do not easily fit into. This, however, is nothing new. Early feminists and sociologists who argued for the recognising of gender and sexuality as an important locus of oppression and exploitation were also viewed with distrust and their knowledge claims deemed irrelevant when fighting for their place within the academy. This was also the case for the study of race and ethnicity and the simultaneous fight to have a university that is diverse (in the broadest possible sense) in its staff and student body, as well as its subject matter. There are countless other disciplines (and the people who advocate the need to study them) who are faced with ridicule, dismissed and derided until they suddenly become established and ‘relevant’. New subject matter and disciplinary perspectives it seems are often regarded with suspicion and treated as a lesser knowledge, despite multiple powerful organising bodies beyond academia recognising the merit, effort and work involved in participating and sustaining a game like bridge. Given the recent world bridge championships as well as bridge’s cultural presentation notably by Agatha Christie, Ian Fleming and more recently on Coronation Street – what can the study of bridge offer those beyond academia? To answer I will use loneliness as an illustrative example.

Back in November 2018, then Prime Minister Theresa May launched a Government strategy to tackle loneliness and appointed a loneliness minister. Loneliness was being linked to a range of long-term health illnesses exacerbated by social isolation, particularly amongst older people. However, it was not just older people who were experiencing loneliness, a recent YouGov poll found that millennials (19-25year olds) reported greater loneliness than any other age group. In the age of the digitally connected and socially isolated, it seems that loneliness is a growing social problem. How and in what ways can bridge help tackle this?

As a four player card game, bridge relies on interaction at the table between partners, opponents and the careful laying of cards to function. Without a partner and two opponents the game does not work at all. In this sense, when playing bridge you form a card playing community of four. Interactions at the table are a fundamental part of the game. The longer you play the game the more the skilful your interactions at the bridge table become, leading to winning outcomes. Some of these outcomes include silent solidarity and support for your partner when mistakes are made during play, learning how to read people strategically through card play and managing emotions at play. This process of learning is ongoing and continuous and can be challenging, strange and often difficult to grasp. It is however always sociable.

Given that we live increasingly lonely lives where many people can spend days without interacting with anyone in a face to face manner, perhaps learning to play bridge and participate in maintaining a small community of four will go some way to combating isolation and loneliness. Playing bridge (socially or in a club) can help to foster a sense of belonging and connection, so much sought for and often so impossibly hard to find. Exploring this is one of the intended aims of the bridge research I am part of, as well as unpacking a whole host of other questions and challenges about the game. Challenges that face the bridge community include gender discrimination at club and elite level and teasing apart the hierarchies between bridge players, as well as looking at the financing of the game, ethics at the table, the ageing population of bridge and many more other developing topics and ideas. All the while not forgetting that these bridge specific questions are embedded in and linked to a world riven by inequalities, isolation and ongoing discrimination and division. Academically researching the card game bridge can speak to that world and its challenges (as I briefly illustrated through loneliness) as well as offering spaces to belong and interact whilst also reproducing some of those inequalities. This is why bridge research (and the academics attached to it) should be taken seriously, for it is when we as academics can speak to, challenge and illuminate ongoing social problems and issues that research becomes most powerful, relevant and socially useful.

References:

Breeze, M. (2015) Seriousness and Women’s Roller Derby: Gender, Organization and Ambivalence London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Miriam Snellgrove is a Research Fellow on the Keep Bridge Alive project led by Professor Samantha Punch at the University of Stirling.

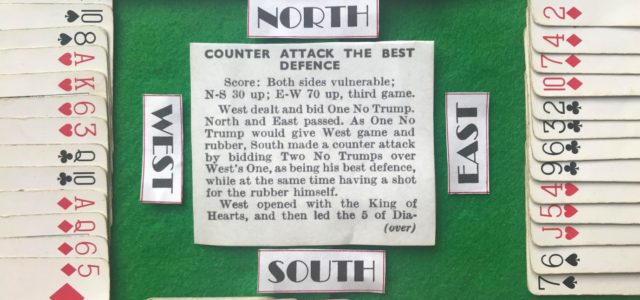

IMAGE CREDIT: Author’s own