Stephanie L. DeMora, Loren Collingwood, and Adriana Ninci

As recently as just a few months ago, Stand Your Ground (SYG) laws were used to justify killing as self-defense. In Georgia, three young men were shot and killed in what is being called an attempted murder. In the most well-known SYG case, George Zimmerman claimed self-defense in the murder of Trayvon Martin in Florida in 2012.

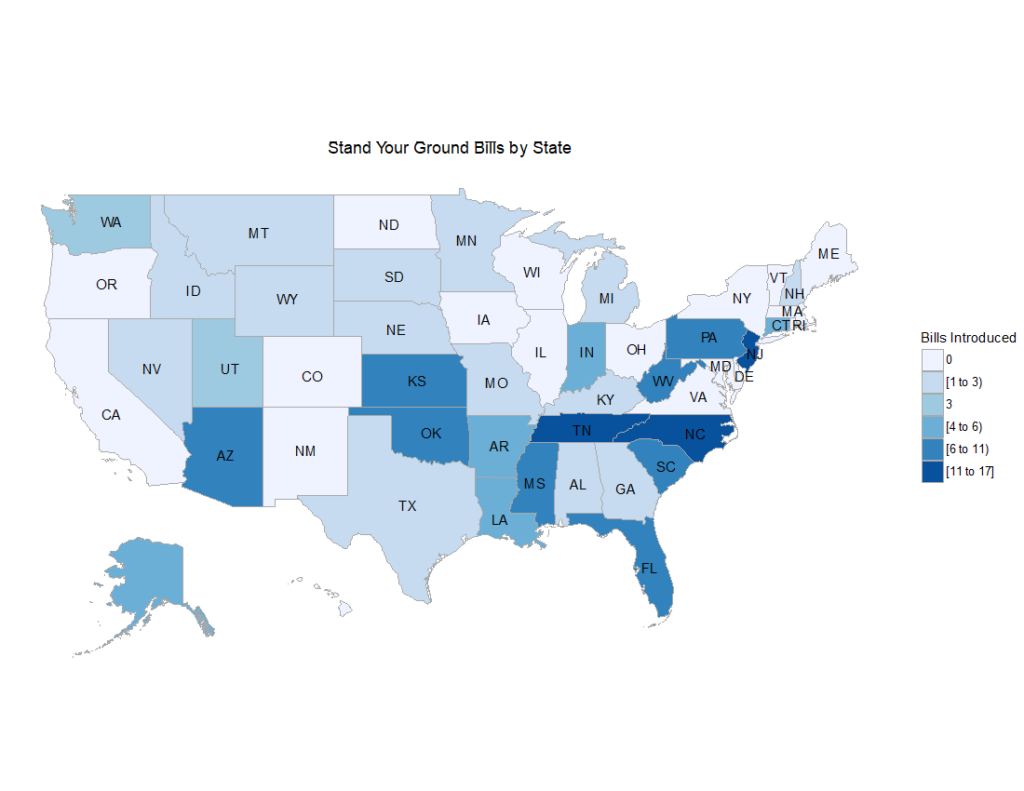

Florida was one of the first states to pass Stand Your Ground or No Duty to Retreat legislation in 2005. SYG legislation then spread rapidly to many states throughout the country. This adoption is most common in the Southern, Midwest, and Southwest states in the United States, and is far less common in the Northeast and West Coast regions. Research shows a significant increase in homicide rates in states with Stand Your Ground laws. Our research shows that SYG bills introduced and laws passed after 2005 were not only similar in content to Florida’s original SYG law, but were almost textually identical from state to state. We investigate this phenomenon further in our recent Policy & Politics article entitled “The Role of Super Interest Groups in Public Policy Diffusion.”

We contend that the growth of Stand Your Ground laws is due to the influence of a particular type of super interest group — which we conceptualize as a sustained organisation. These organisations are financed well enough to provide resources to legislators and their campaigns across the United States, and act as policy experts, thus lowering legislator information costs substantially. Our theoretical intervention juxtaposes sustained organisations with single issue groups, like the National Rifle Association. These latter powerful organisations pursue policies within single issue areas (i.e., guns), but sustained organisations like the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) provide a one-stop shop for legislators across policy domains. Over time, this builds the sustained organisation’s reputation as a go-to corporation to provide trusted model legislation over many years. Finally, these organisations provide private membership where business deals and secret meetings can take place—potentially cutting out public input in the policymaking process.

We conceptualise sustained organisations as a spiderweb of networks through which a central node organises the exchange of model legislation and money to the outer nodes, which typically include legislators and powerful corporations. Corporations push their interests and large sums of money into the central node of a super interest group, and model legislation is pushed out to legislators who then introduce pre-canned bills to their state. This often results in the rapid diffusion of specific policies throughout the country, including SYG, prison privatisation, anti-sanctuary policy, and education privatisation.

As it turns out, a powerful sustained organisation, the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), stamped Florida’s SYG as ‘model’ legislation shortly after Governor Jeb Bush signed the bill into law. This process is standard operating procedure for a sustained organisation. ALEC brought together corporate entities and legislators across the American states to craft model legislation, then employed its vast network to promote SYG around state legislatures. According to their website, ALEC claims nearly “one-quarter of the country’s state legislators and stakeholders from across the policy spectrum” in their membership.

To capture ALEC’s influence, we compared ALEC’s SYG model bill against every single SYG bill introduced into the American states between 2005 – 2017. In order to do this in a reliable and reproducible way, we ported freely available plagiarism software and wrapped it into an R package that facilitated the efficient analysis of plagiarism detection output. This approach is significantly more accurate and contextually applicable than the bag of words technique known as cosine similarity. We found striking similarities between ALEC’s model bill and bills introduced into U.S. state legislatures.

To conduct our research, we collected 153 bills that dealt with “Stand Your Ground”, “No Duty to Retreat”, or “Castle Doctrine” from the LexisNexis database. LexisNexis is a company used primarily for legal research. It grants researchers access to a comprehensive listing of state bills, bill history, and bill texts. We then manually read through the bills to ensure that our corpus was entirely made of SYG legislation, discarding any irrelevant bills.

In order to compare the text of each bill to ALEC’s model legislation individually, we produced the overall word count and percentage of text that overlapped between the two documents. This procedure enabled the normalised quantification of similarity between each introduced bit of legislation and the text of ALEC’s model legislation. We found that, of the 131 introduced SYG bills in our collection, about a quarter lifted at least 30 percent of the state bill directly from ALEC’s model bill. The vast majority of the bills shared over 400 exact words and phrases in common with the model legislation. In one striking example, we found that West Virginia’s 2734 House Bill overlapped the model legislation by 849 words—which made the bill ~80 percent identical to the ALEC model.

Generally speaking, while state laws and statutes are inspired from the original bills, they don’t necessarily contain bill language verbatim. Nonetheless, we examined whether SYG-related laws retained any of the language proposed by ALEC’s model legislation. We collected all of the laws, statutes, codes, and ordinances enacted in the American states and made the striking discovery that several had retained significant portions of the original model language. For example, take a look at the similarity between this segment of Kentucky’s 2006 enactment 192 and ALEC’s model legislation:

| Kentucky 2006 | ALEC Model Legislation |

| A person is presumed to have held a reasonable fear of imminent peril of death or great bodily harm to himself or herself or another when using defensive force that is intended or likely to cause death or great bodily harm to another if:

a. The person against whom the defensive force was used was in the process of unlawfully and forcefully entering, or had unlawfully or forcefully entered, a dwelling, residence, or occupied vehicle, or if that person had removed… |

A person is presumed to have held a reasonable fear of imminent peril of death or great bodily harm to himself or herself or another when using defensive force that is intended or likely to cause death or great bodily harm to another if:

(a) the person against whom the defensive force was used was in the process of unlawfully and forcibly entering or had unlawfully and forcibly entered a dwelling, residence, or occupied vehicle, or if that person had removed… |

The similarities between these texts continued, but for the sake of space, we have trimmed our example to about 80 words. Overall, there were 700 overlapping words between these documents. Initially, we expected sustained organisational influence to diffuse model content widely geographically, but we had not anticipated the depth of its reach. Model legislation seems to trickle down into the laws and statutes affecting citizens in several of the states analyzed.

Stephanie L. DeMora is a Ph.D. student in political science at the University of California, Riverside. Loren Collingwood, is an associate professor in the Department of Political Science at University of California, Riverside. Adriana Ninci is a PhD student in political science at the University of California, Riverside.