Magali Peyrefitte and Erin Sanders-McDonagh

The bright, glaring neon lights of Soho have long illuminated its deviant character, signposting gay bars late night drinking dens, sex shops and brothels, burlesque venues and strip clubs – all of which constitute the fabric of the night-time economy in this central London location. Indeed, we argue here that the neon lights of Soho are central to its reputation, and have an important impact on the development of its uniquely risqué character. Our ethnographic research, collected from 2015-2018 in this vibrant area of London, documents seismic shifts to the lightscape of Soho that reveal drastic socio-cultural and economic structural changes as a result of gentrification.

In recent years, Soho has experienced a rapid transformation that we suggest is part of a process of top down sanitisation, which we term ‘hegemonic gentrification’. The gentrification of Soho can best be understood as a clear and strategic desire from both politicians and developers to remove the more overtly sexual elements to make way for something more sanitised. In parallel to the disappearance of neon associated with the sex industry, we observe that neon signs in Soho are increasingly being used by ‘clean-up’ venues that are new to the area as a way of demonstrating their authenticity. These shifts in the retail landscape, and the changes to neon in particular, are an example par excellence of the process of hegemonic gentrification that we can observe in the lightscape of Soho.

Neon as signifier and signified

In many cities around the world, neon lights are often associated with bawdy night-time entertainment. The neon lights of Las Vegas, for example, lit up this shrine to debauchery in the Nevada desert in the 1950s and 1960s, and are still famous as their association with gambling, drinking and sex continue to define modern day Vegas. John Urry’s work (1995) on place-making helps us understand the significance of certain cultural signs on the creation of a city’s unique identity. He argues that different places come to be known or associated with specific cultural markers –Paris and the Tour Eiffel, yellow taxis in New York City, the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco – these are markers that make a place, and direct the visual gaze of those of visit these places. Urry argues these are important for how people come to understand a space or place – and suggests these markers become signposts– that are ‘designed to help people congregate and are in a sense an important element of the collective gaze’ (Urry, 1995: 139).

While London has a number of ‘markers’ that are associated with the city more generally, in Soho, neon functions as a marker of place for the collective gaze. In the 1950s, the sex industry established itself in Soho, and continued to grow for the following three decades. Many of the neon lights that marked out these sexualised venues were created by Chris Bracey, a neon artist who is well-known for having illuminated Soho’s sex industry at its zenith in the 70s and 80s. Despite being long-closed, the sign for the ‘Raymond Revue Bar’ was recreated by Chris and Marcus Bracey who were this time commissioned by Fawn and India James, the granddaughters of Paul Raymond and heiresses to his estate. It has been integrated to the new facade in the redevelopment of Walkers Court : its garish colours splashing onto the newly cobbled streets and hipster food stalls (another shift in the retail landscape), giving those who visit the area a bright reminder of what Soho used to be in the form of a re-invented cultural heritage.

In 2014 at the time the ‘Raymond Revue bar’ sign was re-erected, the lights of Madame Jojo’s went off on the same building. The cabaret used to draw in large crowds of queer folk and pleasure-seekers, tempted by the saucy burlesque shows that were bending gender norms long before it was fashionable to do so. Although it was a well-established and profitable venue, Madame Jojo’s saw its licence revoked on spurious grounds, shortly after an altercation between its security staff and a customer. Many have argued that the altercation was little more than a pretext for closing the transgressive venue, and we can see similarities in other parts of the western world where zoning laws and licensing have been employed to control and regulate erotic venues –including London’s sex trade in Soho.

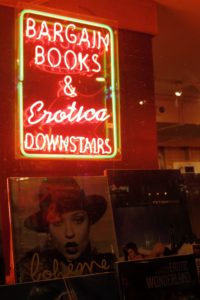

Neon lights were once symbolic of Soho as a vibrant, deviant, transgressive space. They now constitute an urban heritage landscape that is part of its sanitised commodification. In Soho, significations of neon lights reveal a critical aspect of gentrification processes – as many of the shops/venues that have a long and established history in Soho (particularly sex shops although in fewer numbers) still use neon as a way to mark themselves out. Alongside these stalwarts, newer non-sexual venues often use neon ironically, creating a juxtaposition that reveals a great deal about the importance of lighting in how we make sense of the city.

Fragment Methodologies

We maintain that the changes to neon are relevant to the story of Soho and recently of its gentrification, and with our research we have devised a methodology that takes into account the importance of multi-sensory experiences, framing it around the idea of fragments. We have thus developed an original approach to mapping that include different sensory fragments representative of change in Soho. Neon is one of those fragments that form the visual, aesthetic, sensuous and even sensual landscape of Soho that remains both fascinating and exciting although no longer necessarily transgressive. Our mapping of neon lights is inscribed in an anthropology of luminosity that considers the socio-cultural specificities of the experiences and the materiality of light (Bille and Sørensen, 2007:265). It has first constituted in a content analysis of the different types of lights that make-up Soho, also allowing us to create a visual record and simultaneously, an archive of Soho’s lightscape (past and present).

Soho is only a square mile but has a high concentration of shops using neon (old and new). As such it requires a systematic approach and we have particularly concentrated on some of the main arteries in order to be more thorough and exhaustive in our count. These were Old Compton Street, Brewer Street, Wardour Street, Broadwick Street, Berwick Street, Peter Street, Walkers Court, Dean Street, Frith Street and Greek Street. Quantitatively, we found that the great majority of neon lights were now found in restaurants and bars as well as a range of retail shops that were not related to the sex industry. Around only 10 neon lights were found in the remaining licensed and unlicensed sex shops as well as erotic boutiques. Departing from this quantitative snapshot of the transformation of the retail landscape, we have also looked at the visual language of neon lighting through a semiotic lens. Neon functions as a metaphor entrenched in a mythology of modernity that has managed to perpetuate itself and continues to hold associations with urban transgression and depravity.

New neon in old Soho

In Soho, the new neon signs very much work as an echo to its past and its popular culture. We can first site the example of, ‘Lights of Soho’, a private members’ club that also functioned as an art gallery. While the venue closed in 2017 (it opened in 2014), its presence exhibited for this period a striking collection of ‘antique’ neon signs that were presented as artefacts of the area. Indeed, we maintain that the lights on display in the gallery were seen as desirable only as far as they were evocative of the bygones of the sex industry.

Other neon lights make clear references and innuendos to Soho as a red-light district with light tubes often using a colour scheme more traditionally associated with the aesthetic of the sex industry. The most striking example of this kind of titillating detournement can be found in a window shop on Old Compton with no signage other than a piece of twin neon lighting (two sets of bright lips advertising for peep shows and indicating a video store) and another one advertising ‘Live Nudes’. The red light bulb and the other neon above the door suggestively invite you to ‘Come’ in what turns out to be a Mexican restaurant alluringly disguised as a sex store. These kind of neon lights cannot however simply be envisaged as an aesthetic homage. The commercial and advertising potential of neon is what has historically ensured its popularity and its intimate relationship with the rise and success of global capitalism (Ribbat, 2011). Making clear references to Soho’s past, the new neon lights are also in line with the capitalist endeavour to brand the area ‘edgy but not seedy’ as claimed by Soho Estates, one of the largest landowners in the area, and a key driver in this process of gentrification.

More generally, urban illumination is a story of modern progress and has contributed to the development of the ‘24 hour city’ as well as to urban rationalisation (Ribbat, 2011). The lightscape as well as the soundscape and the smellscape of a city are key elements in placemaking and in the design of place – other examples include the Blackpool illuminations, the Christmas lights on Oxford Street, the Diwali light festival in Leicester . Lights work to ensure the economic viability of cities that now must work to accommodate the needs of consumers rather than citizens in an increasingly commercialised and neo-liberal context. In Soho, neon lights are generally on day or night and as such do not simply serve the purpose to attract the attention of customers in the nocturnal landscape of the city as is the primary function of neon. The new neon in particular calls for a different interaction with the place. They are no longer principally associated with the nightlife economy but appear to create new associations in a place paced by rhythms that inform us that the lightscape of Soho must be attractive and inviting for day revellers, tourists and shoppers who want to enjoy its symbolic and sensuous experience during the day as well as at night. Neon lighting becomes one of the visual and material signifiers of what Hubbard would refer to as a ‘spectacle to be consumed by the middle classes’ in the gentrifying city (Hubbard, 2017: 4).

Our mapping thus reveals changes in the retail landscape which ultimately have wider consequences on who or what is included/excluded from certain spaces, as cities work to re-invent themselves to accommodate consumer populations. In the case of Soho, the re-designed lighting is a product of a strategy that aims to sanitise and homogenise this part of London, to make it more attractive to the ‘right’ kind of tourist and customer. We can see similar processes in Amsterdam, as they attempt to clear-up the red lights of de Wallen to attract a more genteel and respectable consumer. The neo-liberal dynamics of urban economies and the transformation of the city as a marketplace consequently has an impact on local communities. Neither Amsterdam nor Soho are just spaces of consumption, they are home to a diverse population of people who live and work there, and who also feel the strains on this changing landscape.

There are however evidences of contestation and resistance by third sector organisations like Soho Society and Save Soho, groups who have campaigned against the forces of neo-liberalism and its impact on the area and who are working to try to protect the ‘edgy’ nature of Soho. We elsewhere argued for the importance of queer and alternative spaces in Soho that are inclusive of a wide range of people and we continue to aim to contribute to dissident voices by mapping changes from a multisensory perspective that reveals the everyday lived experiences of gentrification.

References:

Bille, Mikkel and Sørensen, Tim Flohr (2007) “An Anthropology of Luminosity: the agency of light” in Journal of Material Culture, 12(3): 263-284.

Hubbard, Phil. (2017) The Battle for the High Street: retail gentrification, class and disgust. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ribbat, Christoph. (2011). Flickering Light: a history of neon. London: Reaktion Book

Urry, John. 1995. Consuming Places. London: Routledge.

Magali Peyrefitte is a Senior Lecturer in Criminology at Brunel University. She is interested in the way people experience space and place in the city. She has worked on a number of research projects using visual and creative methods to collect as well as disseminate data. Twitter: @m_peyrefitte Erin Sanders-McDonagh is a Senior Lecturer in Criminology at the University of Kent. She is a feminist public scholar and researches inequality in different forms. Twitter: @liminologist

Image Credit: Magali Peyrefitte’s own photographs