Dan Welch, Kersty Hobson, Helen Holmes, Katy Wheeler and Harald Wieser

The idea of “circular economy” promises an alternative to the current, environmentally unsustainable, linear economy of “make, use, dispose”. A circular economy would be one in which resources and materials cycle through the economy on the model of a nutrient cycle. For the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, the most prominent non-governmental proponent of the idea, the very concept of waste would be eliminated. Even the notion of “efficiency”—the logic of the steam engine, defined as the ratio of useful output to total input—would be transcended by that of “eco-effectiveness”, highlighting the almost “infinite contribution of materials to the generation of value” (Mylan, et al., 2016: 2). The discourse of circular economy has grown to extraordinary prominence in recent years, in many instances superceding the discourse of “sustainable production and consumption”. The EU, for example, has reframed policy commitments to “sustainable production and consumption” in terms of the circular economy, launching a Circular Economy Action Plan in 2015.

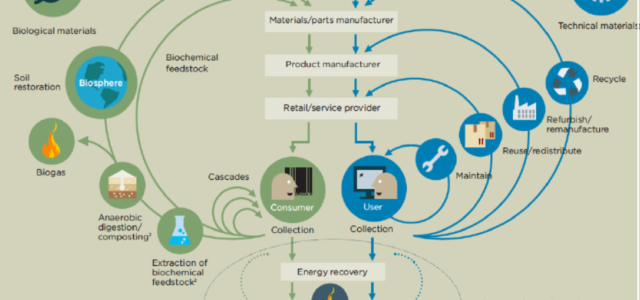

As Gregson et al. (2015: 221) note, while “idealized visions of the circular economy” are of a new, producer-led, industrial revolution, of “industrial symbiosis”, the reality of policy and practice is, thus far, largely one of enhanced, post-consumer waste management. For the EU Circular Economy Action Plan, in somewhat less utopian mode, circular economy is understood as the project of transforming linear production-consumption systems to ones “where the value of products, materials and resources is maintained in the economy for as long as possible, and the generation of waste minimised”. Such transformation involves not just radical changes to industrial processes and product design, but to business models—for example from sale-and-ownership to “product service systems”—and consumption patterns. At the consumer end the discourse of circular economy segues with the problematic notion of the “sharing economy”.

Intellectually, the discourse of circular economy is itself a work of recycling: of the inheritance of the field of industrial ecology, of “cradle-to-cradle” design and “natural capitalism”. We would argue, however, that somewhere along the line, much of the social scientific insight into consumption offered to the field of sustainable consumption has been lost in the mainstream discourse of circular economy (cf. Hobson, 2015; Mylan et al., 2016). It tends to fall short in its conceptualisation of ‘consumption’ and ‘consumers’, reproducing an individualised, voluntaristic model of consumption as consumer choice, and consumers as economically rational agents maximising their utility in markets. For example, the EU Circular Economy Action Plan’s section on ‘Consumption’ begins:

“The choices made by millions of consumers can support or hamper the circular economy. These choices are shaped by the information to which consumers have access, the range and prices of existing products, and the regulatory framework.”

Common definitions of the circular economy tend to elide consumption as a critical stage of the economic circuit, even as the “use” stage remains the central pivot to the entire model, as in the diagram from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation above. Furthermore, they often elide the domestic sphere; a crucial site in which the practices that shape how and why consumers use particular products and services are enacted, waste is generated, and where many of the changes in everyday practice demanded by the circular economy will be played out (Mylan et al 2016).

While critical engagement with notions of circular economy are important (see Gregson et al., 2015; Hobson, 2015), our interest is not primarily in critique. Rather, we propose a research agenda that addresses the kind of changes in the dynamics of consumption that models of circular economy presuppose. Research has highlighted how consumption—including its dynamics in the household sphere—is a relatively under-researched area in CE work to date (Mylan et al, 2016; Wieser, 2019). Indeed, only 19% of CE definitions appear to include ‘consumption’ as a key factor in this framework.

A fertile conceptual entry point to this gap is Miriam Glucksmann’s concept of ‘consumption work’ (cf. Glucksmann, 2009), further developed by Wheeler and Glucksmann (cf. Wheeler and Glucksmann 2015). Consumption work is the distinctive form of labour ‘necessary for the purchase, use, re-use and disposal of consumption goods and services’ (Wheeler and Glucksmann, 2015: 37). Consumption work must be understood in terms of the wider configuration of production, exchange and distribution—as well as the specific social practices—in which it is situated.

A particular affordance of the concept is to focus on the various boundaries or continua in socio-economic configurations, and the shift of work to and from consumers across these boundaries (Wheeler & Glucksmann 2015). For example, retailers and service providers increasingly relocate labour from their own operations to the consumer, whether at the supermarket self-service check-out or through e-commerce. Conversely, digital platforms, such Deliveroo and TaskRabbit, have enabled consumption work to be offloaded onto the precariat of the gig economy, and the wealthy can out-source personal consumption work to high end ‘concierge services’. The concept also focuses attention on how work at other stages of the economic process configures consumption work. For example, the specific forms of the labour required for domestic recycling—cleaning, sorting, and putting items on the kerb, or taking them to a recycling station—are vital to the successful functioning of contemporary waste management systems (Wheeler and Glucksmann 2015).

We argue that visions of circular economies and the success of many circular economy business models strongly depend on significant reconfigurations of consumption work. The concept of consumption work reframes the economic process as predicated on the consumer undertaking work to consume (Wheeler and Glucksmann 2015), and thus is especially well suited for understanding the dynamics of circular economy. Consumption work in the circular economy includes simple activities such as refilling reusable containers of household cleaning products, and returning parts and components of products to manufacturers for maintenance. While such activities are apparently not onerous they cut against contemporary notions of convenience and can present serious barriers to uptake. More involved forms of consumption work associated with the notion of ‘sharing economy’ include: the planning and coordinating activities required by models of ‘co-ownership’ or ‘sequential use’ (Wieser 2019), for example, in car-sharing or the use of ‘tool libraries’; learning skills of repair and maintenance; and even acquiring the knowledge necessary to choose products on the basis of the longevity of product-lifetimes. For example, while car-sharing reduces the labour (and cost) of owning a car, there is notable planning and logistical work involved in participating in car-sharing i.e. scheduling use and re-arranging schedules due to the relative inflexibility of car sharing, returning the car, reporting issues with vehicles, and dealing with dirty cars or low fuel, amongst others. Furthermore, while the increased social interactions that such practices as car-sharing presuppose are often blithely assumed by advocates to be a positive, users of such services can experience these as unwanted emotional labour. For example, one study of a commercial car-sharing service found that while users actively sought to minimise the social aspects that the service providers assumed as a core benefit.

Much of the consumption work presupposed by modes of circular economy will occur in the domestic sphere, with strong implications for the gendered division of labour, an area rarely included in discussions of the circular economy. Studies of ‘environmental labour’ within the domestic sphere (e.g. practices such as recycling and preventing food waste) have demonstrated that it is generally unequally distributed within households, with women doing more of this work. The concept of consumption work builds upon Glucksmann’s earlier work on the ‘total social organisation of labour’, and demands revision of conventional approaches to the division of labour. Thus again, it lends itself well to exploring the implications of household circular economy practices for gendered domestic divisions of labour.

System-level representations of circular economy, as well as many specific business models, depend on—and often fail to acknowledge—the reconfigurations of consumption work required for the circular economy to succeed. And yet the actual work consumers need to undertake, to invest in new practices compared to traditional ‘linear’ modes of provision, remains under-explored. Existing research offers some insight into the importance of considering consumption work in the reconfiguration of consumers’ practices under the auspices of the circular economy (Wieser, 2019). However, extant knowledge of consumption work is fragmented, in terms of both terminology and empirical focus. Existing relevant research does ask some questions about consumption work, under different concepts, such as (in)convenience, effort, domestic labour and co-creation, but this variation in concepts makes it hard to undertake direct comparisons between examples.

As such, consumption work has thus far not been studied systematically in the circular economy context, excepting Wheeler and Glucksmann’s research on domestic recycling (cf. 2015). This is a notable gap. Currently, there exists little knowledge about how consumption work in the circular economy differs from consumption work in established configurations of ‘linear’ modes of provision. In this respect, comparative research could provide valuable insights. Such research could take account of not only the gendered division of labour within circular economy consumption work, but also how other socio-demographic factors such as household make-up, class, employment and ethnicity may influence the uptake of and engagement with practices of the circular economy.

References:

Gregson, N., Crang, M., Fuller, S. & Holmes, H. (2015) ‘Interrogating the circular economy: the moral economy of resource recovery in the EU’ Economy and Society, 44:2, 218-243

Hobson, K. (2015) ‘Closing the loop or squaring the circle? Locating generative spaces for the circular economy’ Progress in Human Geography, 40, 88–104

Glucksmann, M. (2016) ‘Completing and complementing: The work of consumers in the division of labour’ Sociology, 50(5), 878-895.

Mylan, J., Holmes, H, and Paddock, J. (2016) “Re-Introducing Consumption to the ‘Circular Economy’: A Sociotechnical Analysis of Domestic Food Provisioning” Sustainability 8, 794

Wieser, H. (2019) “Consumption Work in the Circular and Sharing Economy: A Literature Review” Available at https://www.sci.manchester.ac.uk/research/projects/consumption-work/

Wheeler K and Glucksmann M (2015) Household Recycling and Consumption Work: Social and Moral Economies. London: Palgrave McMillan

Dan Welch is a Lecturer in Sociology and the Sustainable Consumption Institute at the University of Manchester. Kersty Hobson is a Senior Lecturer in Human Geography at Cardiff University. Helen Holmes is a Research Fellow in Sociology and the Sustainable Consumption Institute at the University of Manchester. Katy Wheeler is Senior Lecturer in Sociology and Deputy Director of the Centre for Research in Economic Sociology and Innovation (CRESI) at the University of Essex. Harald Wieser is a doctoral researcher in the Sustainable Consumption Institute at the University of Manchester. This article draws on a scoping study funded by the Sustainable Consumption Institute (see Wieser 2019).

IMAGE CREDIT: Ellen MacArthur Foundation