Claire Chambers

A recent news story about refugee writing that has attracted much attention worldwide concerns Behrouz Boochani. This Kurdish Iranian refugee texted the bulk of his Farsi memoir No Friend but the Mountains (2019) on WhatsApp to his translator while imprisoned for five years on Australia’s notorious refugee processing centre Manus Island. His creativity in the face of unfathomable cruelty functions as a timely reminder of the power of words. In the formulation of this special issue’s editors, Boochani speaks up to those who talk down to him and try to silence his agile thumbs. In doing so, he fashions imaginative worlds out of his constricted circumstances.

At the time of writing, violence continues to deflagrate in the Middle East, Central Asia, and North Africa, and the global refugee catastrophe (which reached its high-water mark in 2015) is still in full flow and ruining lives like those of Boochani and his camp-fellows. It should not be forgotten that the cause of this ferocity and displacement derives in large part – whether purposely or as collateral damage – from both classic colonialism and newer forms of imperialism. British strategies in Mesopotamia and the Great Game in Central and South Asia, through Cold War American sabre-rattling, the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and the lack of an exit strategy in recent interventions like those in Libya and northern Syria: all need to be indicted in analysis of the current situation.

Amid and against the greatest human rights catastrophe of the twenty-first century, authors from some of the nations most affected by the global refugee crisis are making their voices heard through fiction. I have selected works by three refugee men authors, Hassan Blasim (Iraq), Abu-Bakr Khaal (Eritrea), and Hasko (Syria). Unlike Boochani who wrote Persian nonfiction after heading east to his ultimate incarceration in the Antipodes, these three writers respond through fictionalizations in Arabic of the perhaps more familiar refugee journey to Europe. Their gender matters, for the majority of those who risk their lives on substandard boats to make the dangerous journey across the Mediterranean Sea are men. I draw on these three writers because of their vivid references to desperate boat journeys across unforgiving seas, in which deep waters and terrifying shipwrecks loom large. Taken together, these fiction writers send a shot across the bow, warning of the scale and impact of the refugee crisis, as well as the importance of attending to refugees’ stories.

Hassan Blasim

One writer who represents the perils of asylum-seeking with particular acuity is an Iraqi refugee based in Finland, Hassan Blasim. In his short story collection, The Madman of Freedom Square (2009), Blasim depicts the trauma experienced by those who leave Iraq, as well as those who stay, in the devastating wake of two Gulf Wars. In his story, ‘The Truck to Berlin’, Blasim establishes a grimly comic tenor for the narration of refugee tales:

Obviously you already know many similarly tragic stories of migration and its horrors from the media, which have focused first and foremost on migrants drowning. My view is that as far as the public is concerned such mass drownings are an enjoyable film scene, like a new Titanic. The media do not, for example, carry reports of black comedy.

Here Blasim compares the refugee disaster with the 1912 sinking of the RMS Titanic. He plays on two meanings of Titanic: as well as the disintegration of the supposedly unsinkable ship and deaths of approximately 1,500 of its passengers, there is also the 1997 film starring a young Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet. Blasim’s narrator highlights the predictable reflex through which filmmakers and writers today resort to the parameters of James Cameron’s ponderous tragedy in portraying migration’s ‘horrors’ at the expense of other genres. Simultaneously, the reference to the global hit movie conveys a sense of consumers’ entertainment by the migration spectacle, with spectators almost settling back with popcorn at the ready for this enjoyable horror. He also alludes to his own aesthetic endeavour, which interweaves dark humour with bloodshed and disaster. For Blasim and the other writers I discuss here, the way steerage-class passengers were cast to their fate reverberates into the present-day situation. The overconfidence around the ship that would never sink also chimes with the contemporary optimism of migrants about the better life they expect to find in Europe – in both cases hopes that are dashed as if on rocks.

Abu Bakr Khaal

Abu Bakr Khaal is an Eritrean author who is now based in Denmark after spending many years exiled in Libya. His novel African Titanics (2014 [Arabic 2008]) imagines the passage of Eritrean migrants crossing the Mediterranean in an epidemic of collective madness. The Italian shoreline is figured as an impossible mirage. At first, the narrator, whose name we find out more than halfway through the book is Abdar, is immune to what he views as ‘a pandemic. A plague’. He tells a story akin to the fairytale of the Pied Piper, in which a treacherous bell calls young Africans to a ‘promised paradise’ overseas. But after many years of ignoring his friends’ consuming passion to go abroad, ‘it turned out that the bug had got me anyway and, one day, I woke up wondering how I could have ignored it for so long’. Abdar becomes obsessed with moving away, and ventures across the border with Sudan, on into Libya where he almost dies in the desert, before eventually making his way into Tunisia.

As his novel’s title suggests, Khaal extends Blasim’s image of refugee boats as Titanic ships. From the singular RMS Titanic, readers now encounter a proliferation of new Titanics, encapsulating the numerous tragic stories of the Mediterranean. Khaal’s protagonist declares that he is nicknamed Awacs (the Airborne Warning and Control System) because of his wealth of knowledge about migrant smugglers’ routes. From one temporary home in Sudan, this narrator ‘kept track of the number of Titanics that left North Africa’s shores bound for Europe every summer’, counting the numbers of safe arrivals and the terrible losses. Abdar also keeps an eye on the business and fraud aspect of smuggling, maintaining a keen awareness of ‘exactly how much the brave captains of the Titanics might reasonably demand for passage’. As with Blasim’s writing, Khaal freights his Titanic reference with irony. Passage on the ramshackle migrant ships with their substandard and insufficient rescue dinghies can be sold at vastly inflated prices due to the high demand. Thus the narrator’s allusion to the ‘brave captains’ is bitingly acerbic, in part because the Titanic’s Captain Edward Smith, a hero to some jingoistic Britons, over time came to be viewed as initially reckless and ultimately indecisive when the iceberg struck the ship. Riffing on the 1912 disaster, one of Khaal’s characters mocks the narrator and his friends for their unselfconscious invention of a new Arabic word:

He fell silent and contemplated the group of Eritreans huddled around the TV. Then, ‘Isn’t it you lot that called the boats “Titanikaat”?’ he continued, mimicking our Arabic, ‘As in al-Titanik? […] Damn you all! Who gave you the right to pluralise it as Titanikaat anyway? Are you experts in Arabic grammar these days?’ […] Just so long as you know that seventy per cent of your Titanikaat sink – only around thirty out of a hundred survive! So I guess Titanic is an appropriate name for them after all. Tita… niiiiik,’ he said with force, heavily emphasising the second syllable, transforming it into the Arabic word for ‘fuck’.

Through bilingual wordplay, this character, the Egyptian man Attiah, satirizes the hopelessness of the aspiring seagoers’ position.

Hasko

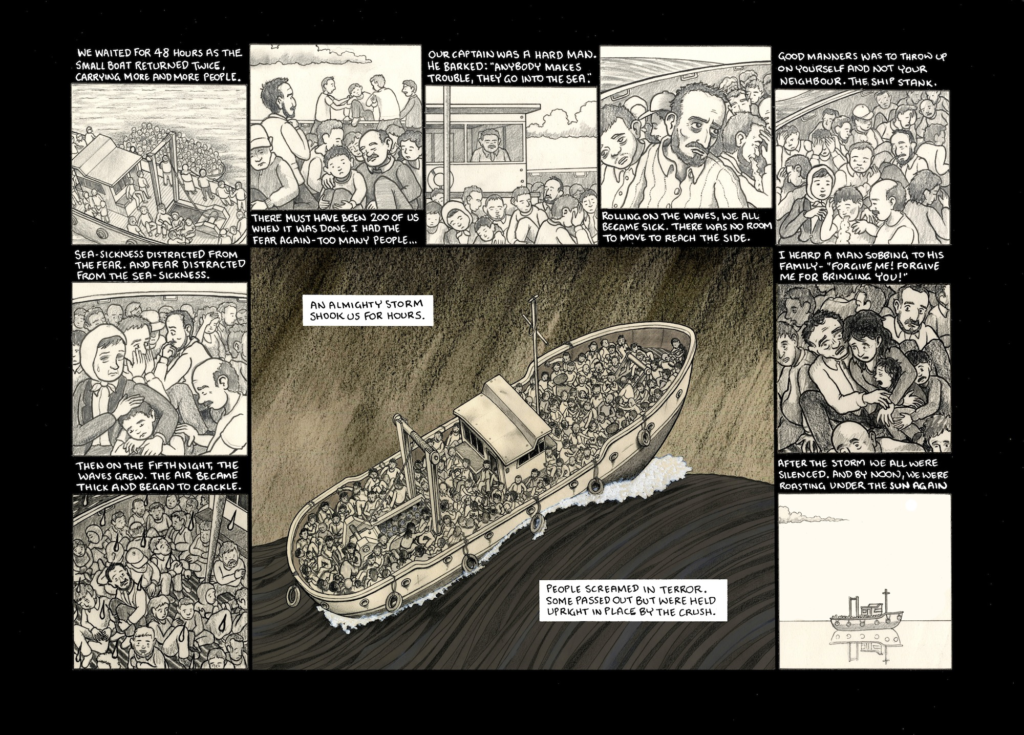

Moving from the two satires, the final text is a graphic short story by Hasko, a Syrian refugee. Hasko’s testimonio was illustrated by Lindsay Pollock for PositiveNegatives and was featured in the Guardian in 2015. The story is bookended by relative calm from Hasko’s safe vantage point in an unknown European country, having been reunited with his family. At the heart of this intensely serious comic, though, is the hardship and trauma of the boat journey. Although neither the ship nor the film Titanic are alluded to in this short story of just six pages, Hasko’s visual symbolism cannot but evoke the iconic black-and-white image of that earlier vessel upended and about to plummet to the bottom of the North Atlantic Ocean.

In the story’s penultimate full page, a panel six times the size of the others takes up much of the space, shot through with intense sepia tones that draw the eye to its image of a ship in trouble during bad weather. The caption, ‘AN ALMIGHTY STORM SHOOK US FOR HOURS’ tersely indicates the suffering of those on board, an impression that is underscored by the smaller panels that ring three of the panel’s four sides. These inventorize the discomfort of being aboard this ship with its tedious waiting around, jostling crowds, and aggressive mariners. Discomfort soon gives way to distress at seasickness, the stench and dirt this causes, and fear and guilt at bringing one’s family into such danger. At the height of the storm, the large panel is emblazoned with another laconic caption: ‘PEOPLE SCREAMED IN TERROR. SOME PASSED OUT BUT WERE HELD UPRIGHT IN PLACE BY THE CRUSH’. Even the calm after the storm brings little relief because of a new ordeal – the ‘roasting sun’. This white heat recalls a widely-accepted Ur-text of refugee hardship, Palestinian author Ghassan Kanafani’s Men in the Sun (1963). In that novella, three Palestinian men of varying ages get baked to death after an unscrupulous smuggler helps them stow away in an oil tanker trying to cross from Iraq through the desert and into Kuwait.

Fragments of Life Stories

If the refugees’ hazardous journey finds resonance with the Titanic disaster, it may also be seen as a new Middle Passage. Especially Hasko’s graphic depiction, with its emphasis on somatic misery, reminds readers of those earlier necroboats of the Atlantic slave trade. Their modern-day counterpart is what postcolonial critic Homi Bhabha has recently and aptly called ‘the wave of death in the Mediterranean’. The idea that people would voluntarily leave their homes to risk their lives in rickety boats at the mercy of ruthless smugglers for economic gain is laughable. Unlike the well-heeled Titanic passengers who were able to escape their capsized ship, these refugees have no home left to return to. The fragments of their life stories impart so much more than human rights reports or academic papers could ever do. The potency of images and words, and the many ways of telling that are available to authors bold enough to look beyond the genre of epic tragedy, are palpable in these writings by refugee men writers.

References:

Bhabha, Homi K. ‘The Barbed Wire Labyrinth: Thoughts on the Culture of Migration’. Philosophy and Social Criticism. 45.4 (2019): 403–412.

Blasim, Hassan. The Madman of Freedom Square. Trans. Jonathan Wright. Manchester: Comma, 2009.

Hasko. ‘A Perilous Journey: Hasko’s Story’. PositiveNegatives.

Kanafani, Ghassan. ‘Men in the Sun’. In Men in the Sun: And Other Palestinian Stories. Boulder & London: Lynne Rienner, 1999 [1963], pp. 21–74.

Khaal, Abu Bakr. African Titanics. Trans. Charis Bredin. London: Darf, 2014 [2008].

Claire Chambers teaches global literature at the University of York and is the author of four books, including most recently Rivers of Ink: Selected Essays (OUP, 2017) and Making Sense of Contemporary British Muslim Novels (Palgrave, 2019). Twitter: @clarachambara

Image Credits:

pixpoetry on Unsplash

‘A Perilous Journey: Hasko’s Story’. Reproduced with kind permission by PositiveNegatives (Creative Commons licence).