Jacqueline Maingard

The Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (2018), an intergovernmentally negotiated agreement, prepared under the auspices of the United Nations, proposes to ‘[ensure] that the human rights of women, men, girls and boys are respected at all stages of migration, that their specific needs are properly understood and addressed and that they are empowered as agents of change’. While the Global Compact has been embraced for its progressive content thanks to the input of many non-government organisations (NGOs), it is seen to represent the political interests of many dominant states and organisations, such as the International Organization for Migration (IOM). One of the key criticisms levelled against it is that it focuses more on the needs of affected states than on refugees and migrants themselves.

It follows then that in order to make its principles fully manifest strategic action is required. Key to this is to hear the voices and see the perspectives of refugees and migrants themselves, if programmes and policies are to respond to their needs and afford them agency. Moreover, extending knowledge and understanding of the experience of refugees and migrants needs mechanisms for articulating their subjective perspectives in the public sphere. Making images that represent refugees and migrants is increasingly important but crucially they need to reflect their concerns and needs from their points of view. Images make the invisible visible and can thus play an important and strategic role in why and how the principles in the Global Compact should be pushed further and applied to serve the interests of refugees and migrants better.

Examples of Image-Making in Migration Research and Campaigns

The processes and content of image making, and matters of the representation and agency of refugees and migrants, shaped the contours of a workshop in July 2019, Image-Making in Migration Research and Campaigns. It was organised under the auspices of Migration Mobilities Bristol (MMB), a Strategic Research Institute at the University of Bristol. Professor Bridget Anderson, MMB’s Director, chaired the workshop, that brought together representatives from refugee and migrant campaigns including, for example, Bristol Refugee Rights, and researchers in NGOs, photographers, filmmakers, and image-makers, as well as academics from across legal, social science, and arts and humanities disciplines. The workshop aimed to consider the use of photographic images of refugees and asylum seekers in migration research and campaigning work, and to explore problems and challenges including, for example, the ethics in using images of refugees and migrants and ways of ensuring their consent. It also aimed to explore alternative approaches to the visual representation of migration and displacement. I participated as Respondent to the event, reflecting initially on my own research on representations of identity in film, and summarising key aspects of the presentations and discussions, which I outline below.

In his publicity for the event, Nariman Massoumi, who organised the workshop, and is a filmmaker and Lecturer in Film and Television at the University of Bristol, identified some of the functions of photographs and images of refugees and migrants. He noted that ‘migration researchers, refugee supporters, campaigners and artists often use photographs to counter negative views, mobilise empathy or promote and explain their findings to a wider public’. At the same time, he proposed, ‘photographic practices also play an important function for refugees and asylum seekers in generating a sense of belonging and maintaining family ties’. In Massoumi’s own film, How Do You See Me? (2017), Massoumi, who moved to the UK with his refugee mother at the age of five, adopts what he calls a ‘domestic ethnography’. His film is an intimate and loving portrayal of the relationship between mother and son that relies on personal, insider knowledge. This interior perspective, mixing family archive with contemporary footage, and integrating images of the Iranian political context, dynamically traces personal histories of the refugee experience from the past into the present.

The focus on individual, personal stories is the kind of approach that several projects presented at the workshop have adopted. From the perspective of the photographer or filmmaker it makes possible a close engagement with specific individuals or a family and in turn allows them to participate with greater trust and therefore with more confidence, and to be more fully and collaboratively involved in all aspects of the project. Equally, projects that use images tailored to respond to the needs of individuals, such as their progress through difficult bureaucratic processes, are more likely to be of support.

Bnar Sardar, an Iraqi Kurdish photojournalist living in Bristol, is one of the only women photographers who has worked in Iraqi Kurdistan. In her workshop presentation she described her photographic project, Two Religions, One Roof that is comprised of 19 black and white photographs. It is, as she puts it, ‘an intimate portrait of harmonious co-habitation between a Christian and Sunni family in Kirkuk, Iraq’. Ghanim, and his family, who are Christian, escaped ISIS in Tel Keppe, near Mosul, and took seven months to arrive in Kirkuk. Widad, a Sunni Muslim, is a widow with three children, who escaped the violence in Najaf. The series provides a deeply intimate view of these neighbours’ lives and a counter to entrenched stereotypes of the region and the religious wars that fuel its violence.

Camilla Morelli, Lecturer in Anthropology at the University of Bristol, presented her project, Amazonimations, a collaboration between anthropologists, animators, artists and the Matsés people in the Amazon rainforest on the Peru-Brazil border. The project is based on indigenous peoples’ stories that are co-produced into animated films with the indigenous participants themselves. A compilation of three short animated films, Amazonimations reproduces the details of life in the forest as well as a subjective representation of young peoples’ experience of the city. Not only are these ‘voiced’ by the participants but the animated drawings reflect their subjective points of view: for example, the teenager who arrives in the city, and stares at the concrete buildings he has never seen before. The stories the films tell, provide an inside view of the migration from forest to city, the trials and tribulations of city life, and the challenges that are often unmanageable and sometimes have tragic consequences.

Images of the city are also the subject of the black and white photographs of refugees who participated in a community photography project at St. Pauls Darkrooms, Bristol, run by members of the Real Photography Company, including founder member Ruth Jacobs. These refugee photographers learned how to make black and white prints and to process them in the darkroom, thus empowering them to complete the full cycle of photographic production. This provides the participants with control over the whole process of producing and printing their own photographs. Apart from the more general benefits of learning a new artistic skill, this positions these participants to make their own choices as to what they represent and how. The photographs offer new, unique perspectives of Bristol city, through the eyes and lenses of these refugees. During Refugee Week in June 2019, they had public exposure in an exhibition at the Vestibules, Bristol City Hall.

The workshop on Image-Making in Migration Research and Campaigns included innovative approaches to the uses of photography to facilitate refugees’ understanding of the complex bureaucratic procedures they have to endure. Victoria Canning, Senior Lecturer in Criminology, University of Bristol, presented the Right to Remain Asylum Navigation Board, which identifies different stages of a Right to Remain application, and the outcomes and actions associated with each. The Navigation Board and accompanying Right to Remain Toolkit include photographs of the legal documents applicants can expect to see at each point, which allows refugees to understand the complex application procedure better and to navigate it with more confidence.

Beyond such uses, the workshop also provided insights into the experiences of those people who are the subjects of images that international NGOs produce. Jess Crombie, Director of Creative Content for Save the Children’s The People in the Pictures, presented the organisation’s research based on interviews and focus groups in the UK, Jordan, Bangladesh and Niger with people who had themselves participated in photographic projects or permitted their children to be photographed. Not surprisingly, the recommendations address ethical matters that include the importance of obtaining the ‘informed consent’ of people photographed or filmed for inclusion in NGO publicity and campaigns, and ensuring further that ‘human dignity is upheld in the image making process, not just in the image itself’.

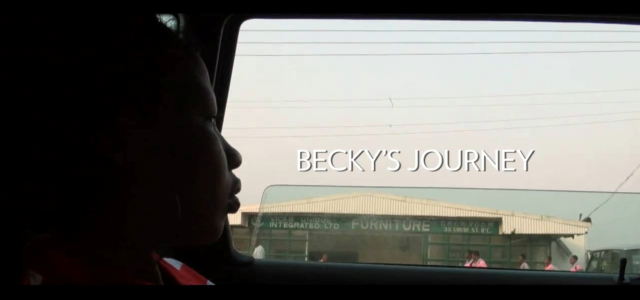

The film Becky’s Journey (2015)

A few weeks before this Image-making workshop, MMB hosted a film screening event in which the filmmaker and researcher Sine Lambech presented her documentary film Becky’s Journey. The issues raised by the film had been a precursor for me to the ideas on which the Image-Making workshop was based, and Becky’s Journey is thus worth referencing as a further exemplar of subjective representation from a migrant’s perspective. It is about a young woman, Becky, who in candid commentaries describes her plans to migrate from Benin City, Southern Nigeria, across the desert via Libya and a sea crossing, to Italy, a horrendously hazardous journey as the film reveals. The film’s importance lies in the fact that it represents Becky’s subjective point of view not only through her first person articulation in her own voice but the positioning of the camera that by extension situates the viewer alongside her. In the opening sequence for example, Becky is presented in a medium close-up shot, showing a side view of her face, while she looks out of the window of a car travelling through Benin City. The shot both aligns the viewer with her point of view and reveals the urban context about which she converses in terms of her desires and aspirations for a better life. This alignment with Becky’s perspective is unfiltered, and raw, as the film builds pace and she tells of the exchange between herself and her so-called ‘madame’ and sponsor in Italy. It humanises, at least visually, Becky’s experience and of those in a similar position, by foregrounding her own view of human trafficking and sex work.

Becky is empowered through the film to speak her mind, but her agency, if indeed she does have agency, notwithstanding her lively self-reflection, does not and clearly cannot stretch to breaking the cycle of fatal desert journeys. In the film she explains in gritty, painful terms how a woman she travelled with had died giving birth in the desert. After the screening, the filmmaker informed the audience that following the film’s completion Becky herself had died. Little is known other than she was on a re-attempted journey through the desert and was pregnant at the time. The shocking effect of this information is all the more intense precisely because the film facilitates a rare intimacy, even a sense of identification, with the life and times of a migrant seeking a better life, who is at the mercy of human traffickers and the accompanying hazardous journeys undertaken across continents.

Conclusion

Returning in conclusion to the ideals of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration it is noteworthy that they include ‘mainstream[ing] a gender perspective and promot[ing] gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls, recognizing their independence, agency and leadership in order to move away from addressing migrant women primarily through a lens of victimhood’. Publicity about human trafficking and the tragic experience of young women like Becky and her fellow traveller, both of whom have died in their twenties, need more innovative interventions and strategies if this ‘mainstreaming’ is to be accomplished. Such films, and the photographs and image-based projects presented in MMB’s Image-making workshop, with their close attention to representing the voices and views of migrants themselves, therefore have a crucially important role to play.

Image-making practices and processes are wide-ranging, and appear in diverse forms that include not only photographs as still images, but also as moving images, displayed in various formats through, for example, websites, social media of different types, and gallery exhibitions, as well as films. The workshop described here underscored the value not only of diverse methods and approaches, but also of their management in terms of ethical responsibilities. This needs to encompass content as well as how the subjects themselves are incorporated and considered in the act of making. The concluding discussion began to iterate yet more complex questions that need further elaboration. Do we over-valorise collaborative and participatory methods? Where do ethics begin and end? What action is needed for fully ‘informed’ consent? How can we take account of broader socio-political campaigns that extend beyond collaboration with an individual?

The diversity that image-making practices encompass make possible multiple forms of imagery. These practices are widely valuable for representing the needs of refugees and migrants, particularly when their subjective experiences are embedded in both the form and content of images, and in the very processes of image making. But there are limits to what such image making can achieve for transforming policies directly. This is ultimately not only down to the image and its making, but to whether and to what extent policy-makers will see, hear and act on what the image tells them about their fellow human beings and the conditions of their lives. This does not mean however that such images are without impact altogether. On the contrary, image making affects public opinions, generates social responses, and inspires social and political activism, all of which can and does influence policy.

Jacqueline Maingard is Reader in Film at the University of Bristol and an Honorary Research Associate at the University of Cape Town. Apart from her interest in representations of refugees, migrants and migration, her research focuses on colonial film histories, and African film audiences. She is the author of South African National Cinema (Routledge, 2007).

Image Credit: Sine Plambech, Denmark, 2014 Becky’s Journey